This summer, the Silchester team(s) were back in the field again for both the Insula III project and the Environs Iron Age project. Amanda Clarke and Dr Cathie Barnett give their updates below…

Never say Never Again: further excavations at Silchester Roman Town

By Amanda Clarke

Professor Michael Fulford, CBE and Archaeologist of the Year, is as near as our profession will get to having Royal Navy Commander James Bond on its books. And, in true 007 style, and with reference to the 1983 Bond film of that name, we have learnt that The Commander will Never say Never Again.

Mike and I had left a hole in the ground (and in our hearts…..) at Insula IX in August 2014, and had walked away, olive trees in hand (our farewell presents from the participants), never thinking we would be back.

Groundhog Day

Now here I was, returning to Silchester in August of 2015, to set up and run a 4-week project to excavate a 15m by 20m trench in the north-east corner of Insula 111 in the heart of the Roman Town.

The Insula III team

What could possibly lure us back? Insula III has been pivotal to our research excavations at Silchester for several years now. In 2013 and 2014 we opened an area 30m by 30m in the south-east of Insula III with the aim of re-excavating the Victorian trenches (dug in 1891) to reveal the structure the Victorians had thought – excitingly – to be a bath house. This methodology – of walking and digging in Victorian footsteps – proved to be an extremely successful one and allowed us, with the minimum of new excavation, to understand further the Victorian campaigns and methods of excavation, as well as determining at least 3 phases of Roman and post-Roman occupation of this part of the insula.

Palaces and Promises

We returned in 2015 to the north-east corner of Insula III as we hoped, by implementing our established methodology of Victorian shadowing, to uncover further evidence for the early Roman palatial structure (misidentified by the Victorians as a ‘bath house’) we had exposed in 2013 and 2014. This would lead our research in a new and exciting direction, promising an early Roman template of town planning, possibly under the auspices of the Emperor Nero.

Victorian mayhem

The first week of excavation in 2015 revealed several things fairly rapidly to our team of volunteers, Silchester ‘old-hands’ and aspiring 1st, 2nd and 3rd year students. For a start, the Victorians had been fairly brutal in their excavation techniques and had employed a methodology which resembled the path of a modern-day bulldozer. However, silver linings and all that, as the excavators of 1893 had avoided and outlined the extent of the spoil heap of the Basilica-Forum excavators of the 1860’s, who had placed an enormous and intimidating mound of soil from their forum excavations all along the western edge of the North-South Roman street, extending into the north-east area of Insula III. This meant that preserved intact beneath the outline of this spoil heap were undisturbed late Roman and potentially post Roman deposits – something of a holy grail for Silchester archaeologists who have been long intent on illuminating the final years of the Roman town.

Sadly however there was no evidence for the continuation of the large palatial building located in the south-east of the insula – instead a packed stratigraphy visible in the sides of the Victorian trenches promised a different story.

Our second week on site proved an enormous challenge on many fronts; we had to re-employ our JCB to remove the huge depth of Victorian backfill we were confronted with, as we recognised that this Victorian-sorted soil would only enhance our muscles, and not our minds. As well as this, it rained – very hard. For days on end.

A Case of Mistaken Identity

By the start of the third week, the Victorian interventions had been emptied, mapped and plotted, and we now had time to look at what they had left behind. The Victorian plan was a red herring – nothing recorded on it was as we found it – but we did gain further insight into the Victorian psyche. For example, a feature recorded on their plan as ‘HYP’ (hypocaust) and left in situ, turned out to be an early Roman hearth, pedestalled and separated from its context – but still intact, beautiful, and able to be sampled and studied.

The early Roman Hearth

Targeted excavation

The Victorian excavators had not reached the natural ground surface but had instead stopped at an extensive spread of gravel of early Roman date. So, our methodology was to extend downwards from some areas of the Victorian intervention to see if we could stratigraphically uncover the earliest occupation on this part of the insula. This we did, revealing a number of Iron Age features at the base of the sequence.

It’s all in the section

The strategy for the fourth week on site was simple: to record and sample the sides of the Victorian trenches – which contained the story of Insula III from earliest to latest – and to begin stratigraphic excavation of the late Roman tabernae, or small shops which fronted onto the north-south and east-west streets, and lay beneath the dark soils. The remains of these buildings had eluded the Victorians but we were able to recognise them as flint and gravel founded buildings with clay floors, and backyards consisting of gravelled areas delineated by post pads.

Final Thoughts

After 4 weeks on site we ended with a very successful Open Day and were able to present our many visitors with a coherent story about the development of the north-east corner of Insula III. Our work has revealed a complexity of occupation on this central insula, and has provided a tantalising glimpse of the richness of the archaeological record here. Now follows a winter of post excavation to establish the chronology of the area, and the chance to assess the many finds left behind by the Victorians – which included more than 66 coins. See you next year!

Pond Farm

By Dr Catherine Barnett

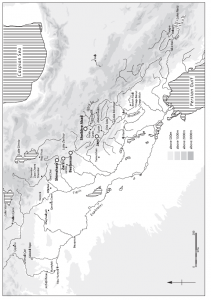

A team of 15 hardy professional, student and volunteer archaeologists, led by project officer Nick Pankhurst, ignored the August-September monsoon season to tackle the site of Pond Farm. The site was suspected to be an Iron Age univallate hillfort and had been chosen as the first in a series of sites to investigate under the new Silchester Environs project led by Prof Michael Fulford.

Four 20x20m trenches were opened up across the site, positioned according to the results of geophysical and coring surveys undertaken earlier this year. Key aims were to date the site and to gauge whether it had a chronological relationship with the nearby Iron Age oppidum that underlies Silchester Roman Town. We also wanted to find out what the site was used for and for how long. Artefacts proved sparse but appeared in just the right places, including a piece of Late Iron Age pedestal beaker recovered from a palisade trench at the end of the defensive encircling bank. The lack of internal structures yet evidence of several phases of earthwork and ditch recutting leads us to suspect that this was not a permanently settled site but one periodically visited over a long time, perhaps as part of a stock management system, with the huge defensive earthworks there to protect valuable livestock.

Much of our understanding will however come from the post-excavation analysis and radiocarbon dating of samples collected during the dig. These are currently being processed, and we’ll let you know what we find in a future post.

For further information on the Environs project please see the Silchester website or email Dr Catherine Barnett at c.m.barnett@reading.ac.uk.

You can also follow Silchester on Facebook and Twitter for the latest updates!