The world has not seen a major volcanic event for at least 25 years, but the tropical volcano Mt Agung on Bali is now threatening to erupt. Mt Agung’s last eruption in 1963 was one of the largest during the 20th century and had widespread climatic effects. Going further back in time, ice core-based volcanic reconstructions reveal events – such as the Samalas eruption in 1257 in Indonesia – that were an order of magnitude larger than the 1963 eruption of Mt Agung.

Because the timing and intensity of eruptions cannot be predicted in advance, they are commonly excluded from projections of future climate. The imminent eruption of Mt Agung raises important questions: How feasible and important is the inclusion of potential volcanism in future climate projections? Will eruptions help mitigating long-term anthropogenic global warming? What is their effect on climate projection uncertainty? How do eruptions affect future climate variability and the likelihood of climate extremes?

Guest post by Ingo Bethke

A recent study by Bethke et al. addresses these problems by inserting a range of plausible volcanic events – each consistent with the reconstructions of past volcanic activity – into 60 climate simulations of the 21st century eith the Norwegian Earth System Model.

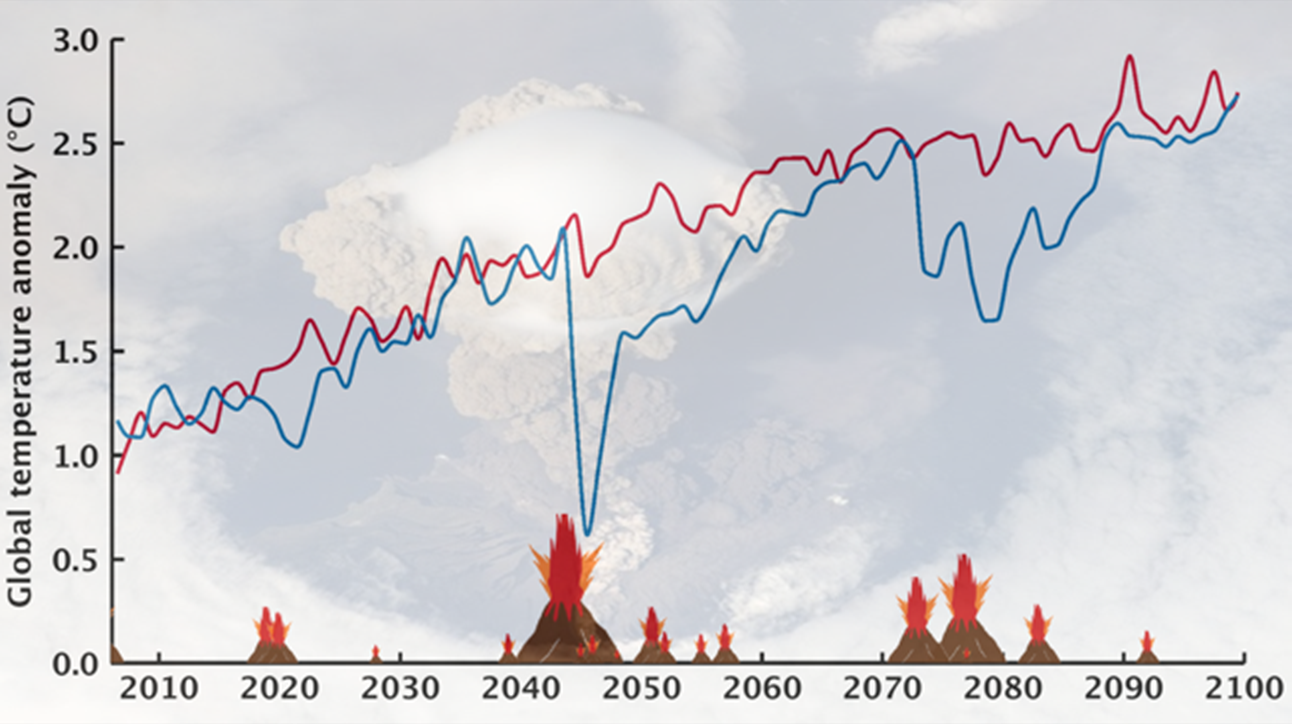

The results project a more variable and fluctuating 21st century climate than suggested by the latest assessments. Compared to simulations without volcanic activity, the projections including potential volcanism show 50% higher occurrence of decade-lasting negative global temperature trends. In a similar manner but with opposite sign, the temperature rebound after the cooling maximum facilitates anomalously positive temperature trends.

In contrast, the effects on long-term climate projections are simulated to be small, with even the most extreme scenario (<1% likelihood) causing little reduction in the end-of-century temperatures (see Figure). Uncertainties in the centennial-mean volcanic activity are, however, substantial and make the exact magnitude of the long-term volcanic impact uncertain.

While future volcanic activity will not reduce the global warming problem, elevated levels of climate variability would exert additional stress on ecosystem and society. Regional climate impact and risk assessments are increasingly concerned with the short-term fluctuations around the climate means. Including potential volcanism in such assessments should therefore be a priority in the future.

It would seem that while the end points in the graph are essentially the same, the average temperature for the century is lower for the scenarios involving volcanism.

According to Wiki, there were twelve VEI =>5 eruptions since 1900. Four occurred in the tropics. There were also at least three tropical >5 VEI eruptions in the 1800s. So further large tropical eruptions can reasonably be expected during the 21st century.

Climate models exclude such eruptions because their timing and intensity can’t be forecast; yet it’s clear that they *will* occur, probably several times, over the course of the CMIP model projections.

Bethke et al. 2017 may be an important counter against future climate change ‘sceptics’ who exploit such events to start the “No warming since…” refrain anew.