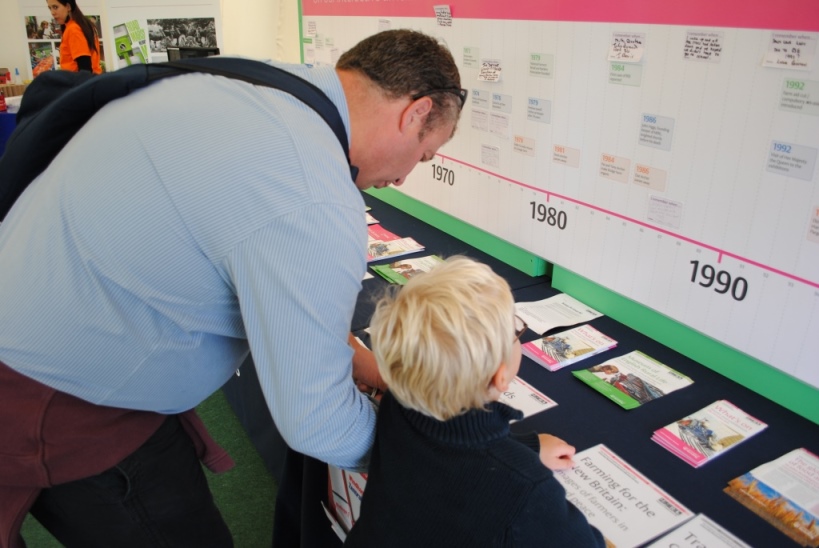

Written by Adam Koszary, Project Officer for Our Country Lives.

Halesowen’s Leasowes Park in the winter.

How interdependent are town and country? How do they rely on each other, and where does one end and the other begin? It is a theme we’re exploring in great detail for Our Country Lives and, considering around 90% of English people live in urban areas, a very relevant one. I wasn’t expecting, however, that my own town would ever factor into the discussion. Halesowen is part of the Dudley borough in the West Midlands. It is decidedly post-industrial and urban, despite sitting on the edge of a greenbelt. However, it also has a wooded, scenic park at its heart which began as one of the first landscaped estates in the country, perhaps even the world. Begun in 1743, Leasowes Park has managed to weather industrial revolution (including having a canal run through it), its encirclement by the West Midlands conurbation, a golf course development and the infamous town planners of the mid-20th century.

An aerial view of Halesowen, with Leasowes Park in the upper right corner.

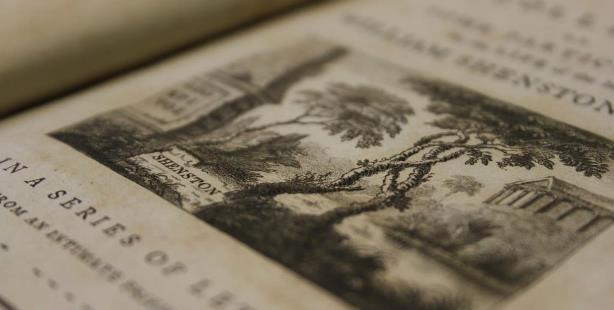

It was designed and built by William Shenstone (1714-1763), who began modelling the Leasowes estate on scenes inspired by pastoral poetry when he inherited the land as a dairy farm. His ashes are now contained in a sizable urn displayed in the Norman parish church of St John, and for his trouble also has a Wetherspoons named after him. Shenstone was among the first to conceive of a garden as a curated journey, pacing walks around the estate with built features and enriching the views with quotations from classical authors as well as his own writings (we have collections of his work in the University’s Special Collections). His Elegy XXI, written in 1746, could very well have reflected his vision for Leasowes:

Lord of my time, my devious path I bend

Thro’ fringy woodland, or smooth-shaven lawn,

Or pensile grove, or airy cliff ascend,

And hail the scene by Nature’s pencil drawn.[1]

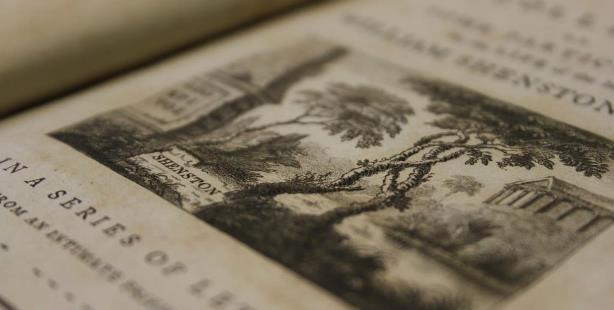

The University of Reading holds Shenstone’s books of poetry.

Leasowes still contains fringy woodland, smooth-shaven lawns and pensile groves, but he combined this natural landscaping with romantic structures such as urns, bridges and even a ruined Priory, constructed from the rose-red sandstone nicked from the ruins of Halesowen Abbey. Visitors came from far and wide to visit this landscape garden, helped in part by printed engravings which attracted figures such as Prime Minister William Pitt, Benjamin Franklin and American president Thomas Jefferson. A friend of Shenstone wrote:

‘Born to a very small paternal estate, which his ancestors cultivated for a subsistence, he embellished it for his amusement; and that in so good a taste, as to attract the notice, not only of the neighbouring gentry and nobility, but almost of every person in the kingdom, who either had, or affected to have, any relish of rural beauties: so that no one came to see the noble and delightful seat of Lord Lyttelton at Hagley, who did not visit with proportionable delight the humbler charms of the Leasowes.’[2]

The estate also had a profound effect on the burgeoning English landscape style, and particularly so on Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, whose tercentenary we will be celebrating in 2016. Landscape Architecture holds particular interest for MERL as we hold the Landscape Institute’s archives. The Institute was founded only in 1929, and work to improve the planning and design of the urban and rural landscape, so we’re delighted to hold their fascinating archives and library.

The estate also had a profound effect on the burgeoning English landscape style, and particularly so on Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, whose tercentenary we will be celebrating in 2016. Landscape Architecture holds particular interest for MERL as we hold the Landscape Institute’s archives. The Institute was founded only in 1929, and work to improve the planning and design of the urban and rural landscape, so we’re delighted to hold their fascinating archives and library.

Leasowes remains a popular attraction for the local area, providing an oasis of natural calm sandwiched between dual carriageways. It was on one of these dual carriageways recently when I had the juxtaposed views of the Black Country sprawl spread out on my left, and on my right a horse grazing in woodland. Horses are a recent addition thanks to a recent HLF grant that has brought the park back to its original form, restoring paths, cascades and reintroducing cattle as well as horses.

A 1748 engraving of Leasowes Park, and the recent restoration of the cascades on the right.

It is in this way that the Leasowes estate encapsulates for me the strange relationship between town and country. Shenstone’s designs are an idealised, man-made manifestation of landscape, and one which pre-empts the long development of English gardens and country estates. When built, Leasowes was an escape into pastoral fantasy but now, trapped in a town, it is for many people the only countryside they know. The idea of the countryside can mean many things to different people – it could be a place of work, a place of relaxation, a place of sport; it could be down the road, it could be half an hour away; it could be local farmland, it could just be a local park; and for some few people, it is something they have only ever seen on television. Exploring what the countryside means to different people through how we view and perceive it is something we are exploring in great detail as part of Our Country Lives, and for me Leasowes Park is a perfect case study.

[1] Shenstone, W., ‘Elegy XXI’, The Poetical Works of William Shenstone, Esq., London: Alexander Donaldson (1775).

[2] Graves, R., Recollection of some particulars in the life of the late William Shenstone, Esq., London: J Dodsley (1788).