I was pleased to hear from my friend that he had been reading this blog, even proving keen enough to sign up for the RSS feed. As well as coping with the stresses of what can evidently be quite a harrowing commute, this particular friend has a busy work schedule and three young children at home. As such, I am surprised that has found time in his busy life to explore what we are up to. I guess it’s entirely possible that he is just humouring me, or perhaps he browses the web on the coach en route to London! Either way, as a roundabout way of thanking him for taking the time to look, I’ve decided to see if I can chart his commute in some way using artefacts, archival materials, and historic photographs from the museum’s collection. My motivations are not entirely altruistic. This is really an experiment to see if I can find interesting things that connect to and perhaps help to contextualise his route.

Here goes… As I don’t wish to reveal my friend’s precise address, I’ll start with a central feature of his home town Watlington, as depicted by Phillip Osborne Collier (1881-1979), a commercial photographer and postcard publisher who worked in Reading from around 1905 onwards. The Collier collection comprises circa 6000 glass plate negatives of places in Berkshire, Hampshire and Oxfordshire. These were produced between 1905 and the 1960s. Unfortunately, these Collier negatives have not been digitised in their entirety so for ease and rapidity of reproduction here I simply photographed them on a light box and inverted the image using editing software. They are therefore in quite a raw state but will hopefully give you some idea of the places depicted. So, lets imagine that my friend begins his day somewhere near to that central staple of English rural communities, the church:

The church in Watlington, early 20th century

This prolific photographer’s glass plate negatives will lead on through the town and into the surrounding countryside. but the church is a nice way to start. My friend lives quite close to it and my family joined his on a visit to see the Christmas tree displays there last December. This provides me with an excuse to add in this Christmas card produced by Collier and featuring scenes from around Watlington:

Watlington Christmas card, early 20th century

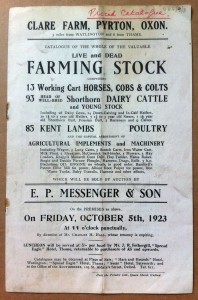

Turning back to my friend’s actual commute, it seems likely that he emerges, bleary-eyed, and cycles out into Brook Street:

Brook Street, Watlington, early 20th century

Because I’m uncertain as to where precisely on the modern-day Brook Street we are in this image, here’s another shot which I think may even show the exit from which my friend most likely emerges of a weekday:

Brook Street, Watlington, early 20th century

I’m sure there are short cuts to be had but as I’m not privy to that fine-grained residential ‘sense of place’ I’m going to guess that from here my friend might turn left into Couching Street, perhaps even using the junction shown in the following photograph (if you look closely you’ll see that its signposted to Lewknor!). However, I suspect he doesn’t travel with a cyclist’s assistant like the distant subject of this image:

Corner between Brook Street and Couching Street, Watlington, early 20th century

My friend’s commute takes him down Couching Street or in that general direction:

Couching Street, Watlington, early 20th century

My friend almost certainly passes close to the old town hall and market place. Collier’s work includes two different views of this particular site, which also reveal subjects relevant to the navigational theme sthat I’m exploring here. The first shot features a horse-drawn vehicle:

Town Hall, Watlington, early 20th century

By comparison, the second shot of this site shows early motor vehicles:

Market Place, Watlington, early 20th century

From here, both Collier and my friend head out into the surrounding countryside. For my friend to have a hilltop perspective like that shown below would entail an inconvenient detour (and possibly more sensible footwear again) but I’ve added this in anyway. It’s not often that the commuters amongst us have the time to take in a vista of our departure point, so I thought he might apppreciate the opportunity, even if the scene appears to be a little hazy as a result of my rushed digitisation:

Watlington 'from the hills', early 20th century

My friend is now out into open countryside, cycling along the B4009 to Lewknor in order to make his bus connection. On the way he passes farmland that is representative of the agricultural community surrounding Watlington. An image (MERL P FW PH2/C108/62) in the museum’s Farmers Weekly photograph collection shows combine harvesters traversing a field close to the nearby village of Britwell Salome. This is not on my friend’s direct route but perhaps helps to communicate something of the kind of farming activity one might have seen in this area during the early 1950s.

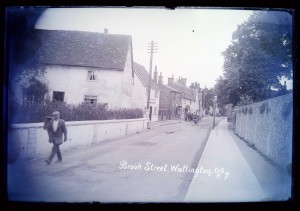

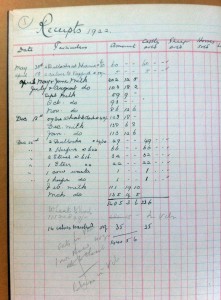

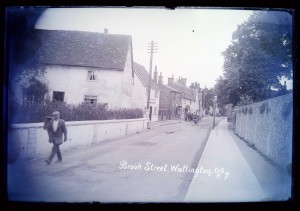

Back to our route, Pyrton is situated part-way between Watlington and Lewknor, northwest of the B4009. Somewhere beyond it lies Clare Hill, which was almost certainly the location of a place once called Clare Farm. The museum holds farm records related to this site, including a receipt book dating to 1922 and bearing the name of its then proprietor, Charles Hall:

Detail of ledger from Clare Farm, Pyrton, 1922

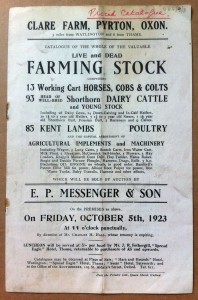

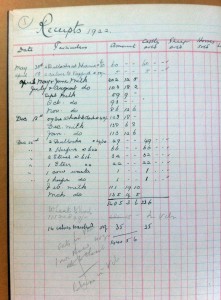

This set of archival papers also contains details of the sale of this same farm in 1923:

Sale catalogue for Clare Farm, Pyrton, 1923

This is probably enough between Watlington and Lewknor (and I may well have exhausted the museum’s holdings relating to this particular area). Suffice to say, the museum appears to hold significant materials associated with the approximate route so far. From here the road takes my friend onwards between the fields to the centre of another nearby agricultural community at Lewknor. The museum holds an artefact – a musket – that was probably once used by a farmer in this very place:

Accession form for musket associated with Lewknor

This brings us to the end of my friend’s cycle ride and the beginning of his coach journey, which follows the motorway from Lewknor all the way to London. I suspect that there are probably numerous artefacts associated with different places situated along the route of the M40. However, my friend will probably have to wait until the project team have worked their data-enhancement magic and we have mapped these holdings in an easy to visualise way!

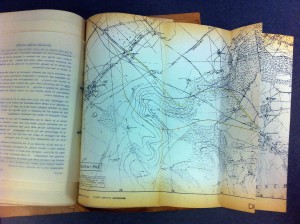

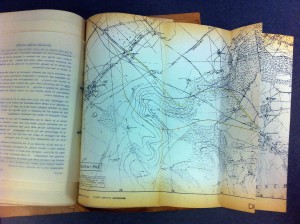

Lewknor on M40 planning map, 1960s

For now lets hope my friend is happy enough to learn of the fascinating papers that the museum holds concerning the impact planning for (and subsequent analysis of) this stretch of motorway, dating to between the 1960s and 1990s. These stem from the rich and detailed archives of the Council for the Protection of Rural England (now the Campaign to Protect Rural England), which include maps showing the intended route as well as papers and correspondence pertaining to the projected impact on the rural area affected:

Map showing proposed route (from Lewknor) of the M40, 1960s

Perhaps later in the project I will revisit this exercise to see what further material has come to light in relation to the M40 route. For now though, let me close with the obscure and limited content I managed to find to link to Shepherd’s Bush, which is more or less where my friend’s morning commute comes to an end. The museum catalogue reveals only a single archival item connected in some (unknown) way with this place. This is a drawing from the archive of the engineering company Charles Burrell & Sons Limited, the catalogue entry for which reads ‘Proposed Power House for Rolling Track (Shepherd’s Bush)’. This particular drawing relates to a rival engineeering firm making it even harder to determine what (and indeed where) this machine was intended for. Here is a detail of the drawing, which does not reveal a great deal more than the catalogue entry:

Detail from engineering drawing

It is nice to end on an item linked with transport, as well as on something about whcih the museum does not currently know a great deal. If anyone knows more about how this vehicle would have been used please comment. The notion that underpins much of what this project (and indeed this exercise) is seeking to achieve is one of empowering the museum’s ‘source communities’ and harnessing the rich body of knowledge and ideas that the wider public can bring to bear on complex collections like thise held here at MERL.

Now I’m heading off to catch my train…