My colleague Alison Hilton (Marketing Officer) recently joined other museum professionals from around the UK at an event held in No. 11 Downing Street in celebration of the success of Museums at Night.

This visit from a member of MERL staff to the heart of government brought to mind something that I read recently, which had been penned by the current incumbent of the property next door, No. 10. The Spring 2012 edition of the Countryside Alliance quarterly magazine features a guest article by Prime Minister David Cameron (2012_Spring_Cameron), in which he writes enthusiastically about modern country life and refers to his own personal experience of different places within rural Britain. Here the PM draws attention to his own rural roots. He was brought up less than 20 miles walk from MERL, in the small West Berkshire village of Peasemore. Somewhat coincidentally, Peasemore just happens to be the location of the pub that will host the winner of MERL’s current photographic competition. I would urge you to enter this soon as the deadline of 22nd April is almost upon us.

Whilst attempting to avoid the political rhetoric of the PM’s article, I was nevertheless struck by a couple of things. Firstly, his characterisation of rural Britain as ‘a real place of mud and muck, proper community ties and incredibly hard-working people trying to make a go of their lives.’ This seems to echo the notion that the countryside might harbour potential to offer a renewed sense of social cohesion, about which I have already posted some thoughts. The piece also appears – albeit probably unintentionally – to echo language that was popular in critiques once levelled at the nascent organics movement of the 1940s, namely that this was an ethereal and unrealistic world of ‘muck and magic’! Putting this to one side for a moment, let’s take a look at how the PM then picks up on nostalgic and romantic ideas of the countryside, attempting to contextualise these within the complex social and economic climate of the present:

‘I love the beauty and history of the British landscape but for me rural life is part of the present, with huge strengths and serious challenges too… it is my constituency of Witney in West Oxfordshire where we [David Cameron and his family] are really at home. It’s a stunning bit of Britain, on the edge of the Cotswolds, with a real rural economy and thriving market towns. You can never forget, as an MP for a seat like mine, that the countryside isn’t a vast museum [my emphasis]. It’s a buzzing 21st-century economy.’

I think that it was the last section that I found particularly problematic. There is a casualness to the popular conception of museums as warehouses of the past that has the effect of pigeonholing them and portraying them as storehouse for objects, technologies, or ideas that were once important but are now redundant, once active but now static. However, much like the PM’s take on the countryside of the 21st-century, I would argue that museums are undeniably buzzing. What is more, they are waking up to their wider socio-economic potential and becoming increasingly effective at measuring their own impact, understanding their value as dynamic sites of engagement, recognising their potential to become active agents of change, and highlighting their important role as interconnecting hubs and facilitators of social enterprise. We don’t even have to look outside the rural museums sector to find the pioneers and architects of this latter approach. The Museum of East Anglian Life and its Director Tony Butler sit at the forefront of the Happy Museum Project, which seeks to bolster the social and economic importance of such institutions within their local communities, and to draw strength and inspiration from the values of people living in these places. So, far from being backward-looking institutions, museums are actually operating very much at the vanguard of David Cameron’s Big Society.

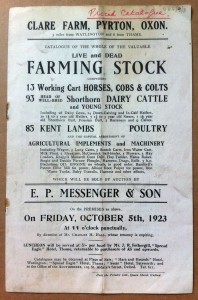

In addition, I would argue that the countryside can operate simultaneously as the ‘buzzing’ economy of the PM’s portrayal and concomitantly the enormous museum that he is keen to declaim against. Farmers and other managers of the landscape (alongside the many diverse people who work or live within it) are not only contributing towards a host of vital modern industries but participating in a vast exercise in stewardship and custodianship. Whether we travel through the countryside, talk about it, or even directly participate in and contribute towards it’s construction and care, we are all able to enjoy the fruits of these collective curatorial labours. This links back to some of the ideas that I think lay behind the very establishment of MERL. I believe that the museum’s founding father, John Higgs, probably drew inspiration from ideas about rural community and localisation that were popular with certain thinkers of the interwar period. This included people like H. J. Massingham, whose artefactual collections Higgs secured for his fledgling museum, and which have recently been fully catalogued as part of the Sense of Place project.

This notion of the nation as a vast open air museum is not really very new. It has links to the national park movement of the 1930s and arguably has its most explicit roots in ethnographic projects that preceded these developments. Indeed, I paid passing reference to one such vision in a recent article about folklore and object-collecting during the late-19th century:

‘On the threshold of a new century, one major folklorist argued that the entirety of British folklore should be thought of in museological terms, with the nation itself the museum and all its vernacular content and attributes—living and obsolete, tangible and ethereal—a distributed but systematic collection. Here the discpline itself became a museum; an historical project in which “specimens” were to be “labelled, ticketed, and set forth for greater convenience”.’

This is far from a redundant notion. I suggest it has a valuable role to play in the present and that the idea of ‘place’ should come to form a central part of how we begin think along these lines. Rural museums should seek to foster the idea of the countryside as a ‘vast museum’, thereby highlighting and capitalising on their own potential to function as key players in the broadening of public understanding about this rich interconnecting web of places, people, and activity. They can become portals, springboards, and stepping stones by which contemporary audiences can enter and begin to understand and enjoy the rural places that make up the massive countrywide display and interactive of Britain. There is nothing shameful in seeing the countryside in these terms. Instead, much like Museums at Night, this is something we should look to celebrate and encourage.

Articles cited:

- David Cameron, ‘Last Word: My Countryside’ in Countryside Alliance, Spring 2012, p.42

- Oliver Douglas, ‘Folklore, Survivals, and the Neo-Archaic: the Materialist Character of Late Nineteenth-century Homeland Ethnography’ in Museums History Journal 4:2, July 2011, pp.223-244

- Alfred Nutt, ‘Presidential Address. Britain and Folklore’ in Folklore 10:1, 1899, pp.71-86 [as quoted in my own article]