(Text of a paper given by Billy Smart at the University of Glamorgan ATRiuM in Cardiff – twice! – at ‘Spaces of Television: The Performance of Television Space’ on Friday 20 April 2012 and ‘Cops on the Box: Crime Drama on UK TV Screens’ on Friday 15 March 2013.)

What I’m going to do today is to reconsider the form that most British television drama took between the 1960s and the 1980s – programmes that were shot in the television studio on multiple cameras, recorded onto videotape, and that used pre-filmed inserts for exterior scenes. I shall attempt this through identifying particular qualities inherent to studio drama, suggesting that there were types of story that could be told especially well in this form.

I shall illustrate this by showing how studio drama told stories through visual details of performance as much as it did through dialogue, exploring this idea through investigating how popular police dramas used rape storylines, showing ways in which the effects of rape were conveyed to the viewer through the non-verbal means of looks and gestures.

Discussion of studio drama has often been predicated around the form’s perceived similarity to the theatre, particularly the naturalist theatre of the 19th century onwards. An early, notorious, declaration of this idea was Troy Kennedy Martin’s 1964 article, provocatively titled ‘Nats Go Home’. For Kennedy Martin studio television drama was inherently naturalist and that was a bad thing, giving primacy to verbal storytelling over visual storytelling. In ‘nat’ drama, the nature of characters and their relationships, abstract themes and ideas were all revealed through dialogue.

Kennedy Martin was emphatic in this belief:

Despite what everyone may say to the contrary, naturalism is not a visual form. The bulk of the dramatic information rests on the dialogue and the visuals do nothing but supplement it. (Kennedy Martin, 1964, p. 27)

I’d like to suggest that this was a mistaken assertion. Although the programme around which I’m basing my case, Hunters Walk (ITV, ATV, 1973-76), was unquestionably a ‘nat’ drama and not a place to see experimental and nonlinear storytelling, it – and other such programmes – could achieve their dramatic effect through visual means – glance, gesture and inference.

Hunters Walk was overseen by Ted Willis, the creator of Dixon of Dock Green (BBC, 1955-76), and bore some affinity to that series, in presenting stories about the crew of one police station, but in this case in a small provincial town (‘Broadstone’, filmed in Rushden, Northamptonshire) rather than London, and scheduled to be watched by a nighttime adult ITV audience, rather than an early-evening family BBC1 audience. It’s a good example of what Brett Mills calls “invisible television” (2011), series that are highly popular (every episode of Hunters Walk was in the Top 20 programmes for its week, and it achieved ratings of up to 16.6 million (Gambaccini & Taylor, 1993)), but which fail to gain the critical or academic attention generally awarded either to quality programmes or shows with cult status – Dennis Potter or Doctor Who. Its also literally invisible television for the most part, as only ten of the 39 episodes survive, and five of those – including the edition that I discuss here – only exist on rather muffled black-and-white 16mm prints, rather than the sharp colour videotape image that viewers would have seen in 1973.

Of all of the major crimes that police have to deal with, rape was the one least often depicted in police dramas between the sixties and the eighties. I’ve only managed to find four storylines explicitly concerned with the investigation of rape (Hunters Walk: Local Knowledge, ITV, ATV, 11 June 1973; The Gentle Touch: Decoy, ITV, LWT, 12 September 1980, Juliet Bravo: Misunderstandings, BBC1, 27 November 1982, The Bill: With Friends Like That…?, ITV, Thames, 27 January 1986). There are very sound reasons why police series avoided rape plots, making the rare occasions when they were attempted of particular interest.

I’ve identified three particular potential problems for rape storylines in police drama;

▪ Content: rape is a disturbing crime to contemplate, and not one that could be depicted. Police dramas could show an armed robbery, but they couldn’t show a rape happening onscreen. Dramatising a crime of a sexual nature ran the risk of either being too shockingly graphic for viewers to be prepared to watch, or too circumspect to be convincing drama.

▪ Tone: rape storylines ran a risk of appearing titillating or salacious. This is certainly a trap that ‘Decoy’, the episode of The Gentle Touch, falls into, in which the glamorous female detective goes undercover as a sexy barmaid who puts herself in positions of danger likely to draw out the rapist, having to be rescued by her male colleagues.

▪ Responsibility: a considered rape storyline can only be pretty depressing. If an armed robber is caught at the end of an episode, the viewer can presume that they will go on to be tried and sentenced, allowing their victims to start to recover. But if a rapist is caught, then the prospect of the case going to trial is traumatic to imagine.

The episode of Hunters Walk that I’m discussing (‘Local Knowledge’ w. Richard Harris, d. Ron Francis) avoids the first two of these pitfalls. The third potential problem – responsibly representing the effects of rape – is an insurmountable one, but the programme makes the grim repercussions of being a rape victim the source of its drama.

‘Local Knowledge’ has a retrospective dramatic structure, starting with the police arriving at the scene of the alleged crime, therefore placing the viewer in the same position as the policeman, having to judge the veracity of the crime and the reliability of the victim from the evidence that they are given. The episode has two concurrent plots, each told in a different narrative mode; the detective work conducted by the police, led by Sergeant Smith (Ewan Hooper).

and what happens to the victim, Christine Lewis (Frances White)

The detection plot conforms to Kennedy Martin’s definition of ‘nat’ drama, through being constructed verbally. The police make sense of the case through language, conducting oral interviews and taking written statements from the witness, victim and suspect, and through discussions amongst each other and with professionals – in one dialectical scene Sergeant Smith goes through the wording of a medical report with a doctor (Dennis Chinnery), discussing its possible interpretation in a courtroom. The vital clue that leads to the suspect’s arrest is also verbal – before the attack he uses the expression “iron bridge” to Mrs. Lewis, rather than “railway bridge”, revealing that he must be a local man, the ‘Local Knowledge’ of the title.

By contrast, Christine’s story is largely silent and conveyed through gesture and expression. I was reading a memoir by the feminist writer Kate Millett while I was thinking about this episode, and was struck by this passage:

How strange the dynamic of persons, their emanations, the effects of their mere movements or expressions. How more powerful and definitive finally than words. (Millet, 1977, p. 155)

which describes how the viewer is made to understand the victim’s story in this episode.

‘Local Knowledge’ achieves much of its dramatic effect through the presentation of small visual details, something that the multi-camera form of studio drama was particularly well suited to do without disrupting the flow of continuous performance within a scene. To give examples of how this works, we see; Sergeant Smith’s wife (Ruth Madoc) deciding to chain her front door when her husband leaves in the night to investigate a complaint of rape;

Mrs. Lewis’ Mother-in-law noticing that Christine isn’t wearing her wedding ring while she sleeps;

Christine leaving her food uneaten;

and the Mother-in-Law almost holding Christine’s hand, but then deciding not to.

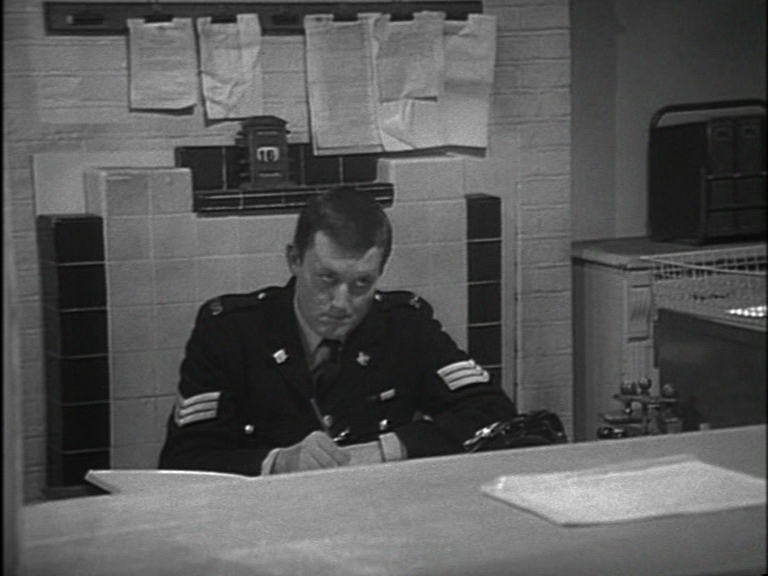

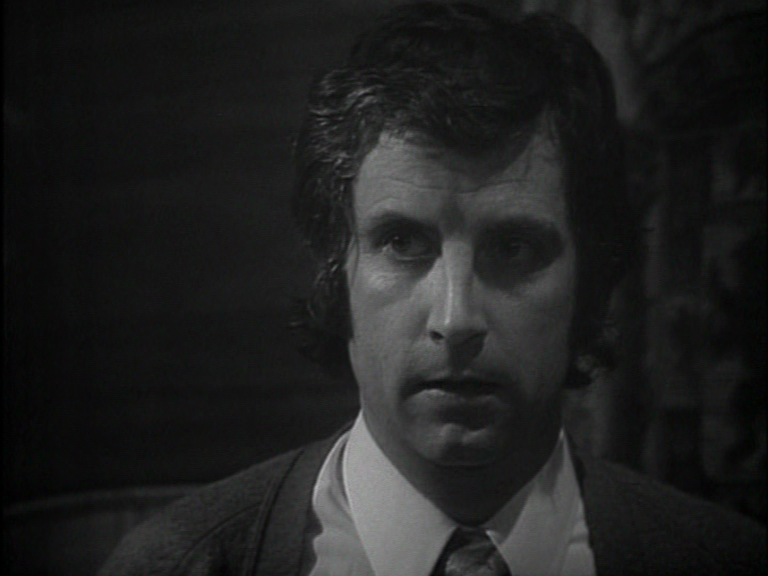

Such attention to detail primes the viewer of Hunters Walk to be attentive to the nuances of characters’ physical movements and facial expressions, such as in this brief scene of Christine waiting at the police station

(Clip 1: One minute: Christine is brought into the Police Station and briefly waits for Sgt. Smith to be able to see her. The Desk Sergeant (Davyd Harries) asks her if she wants a cup of tea, which she declines. Once sat, Christine is seen in a large close-up. Shots of her are alternated with shots of three policemen reacting to her presence. The scene ends with a lingering shot of the Desk Sergeant watching her go.)

In plot terms, there’s no need for this scene to be in the programme, yet it clearly isn’t padding and is doing something dramatically, in giving the viewer a greater understanding of Christine’s character and situation by showing a sequence of looks from the various policemen and her responses to them. To articulate what is being conveyed visually through the facial expressions in this scene, which places great confidence in actors’ ability to convey subtle changes of thought; every time that a policeman looks at Christine, she responds acknowledging their attention, realizes that they are looking at her in a different way than in ordinary social interaction, and the change in her expression registers this realization with discomfort. Because the scene is recorded in continuous time, creating a lifelike sense of hesitancy and awkwardness in the characters’ movements – these aren’t perfectly composed shots – this mood of displacement and unease is accentuated. What is least significant in this scene is the dialogue.

This way of presenting Christine, as a woman who is aware that she is being looked at, is repeated throughout the episode in various forms, whether by her neighbours in the street –

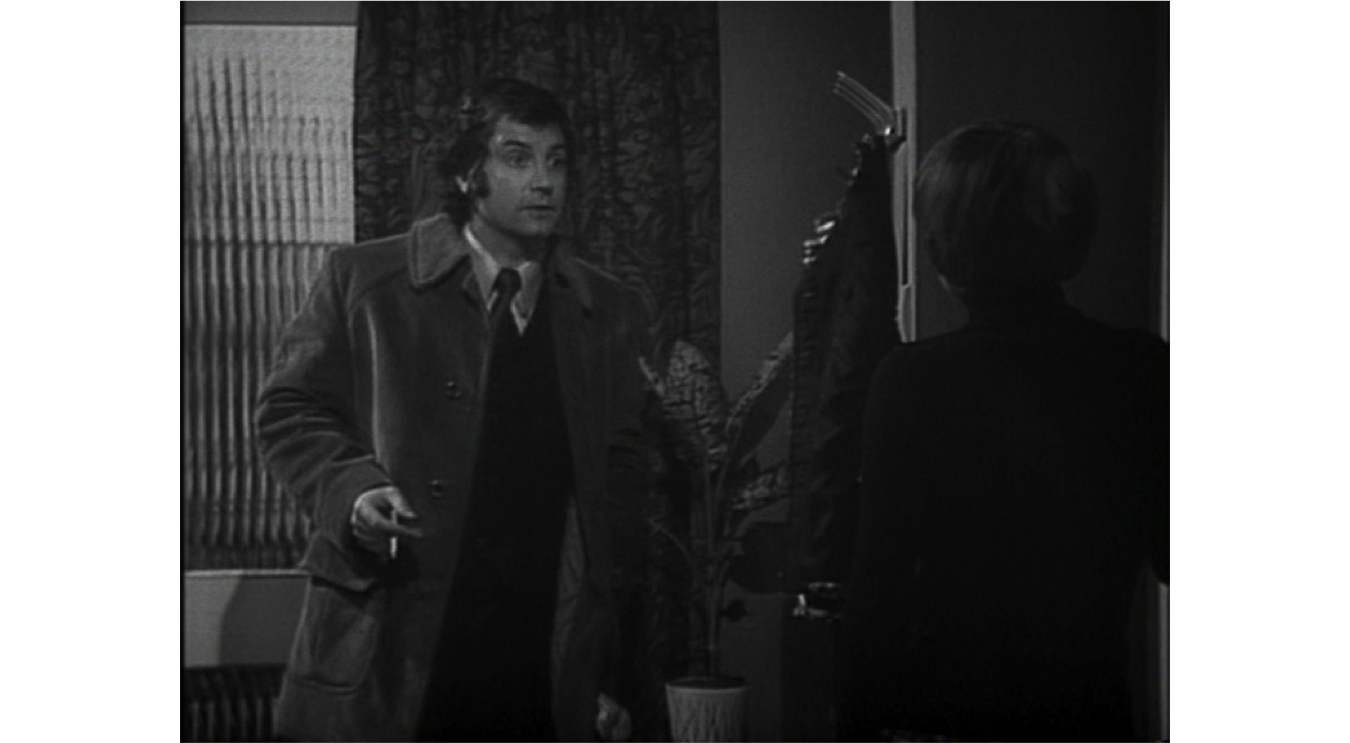

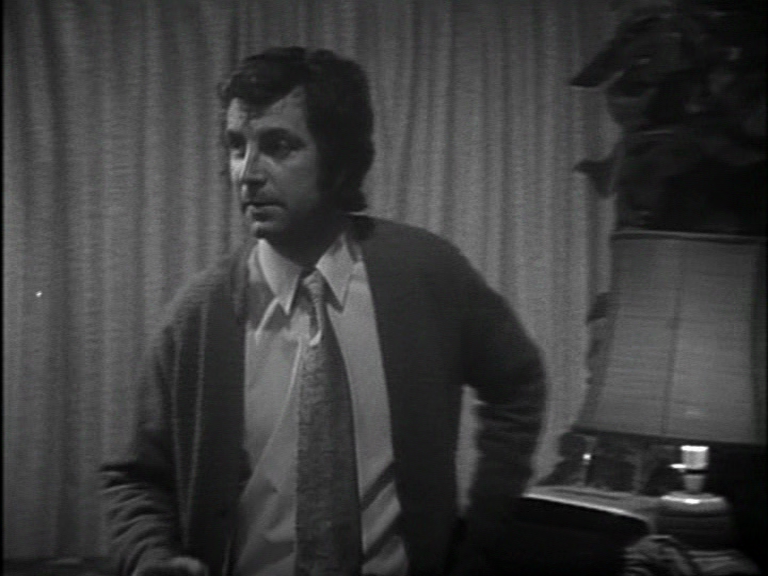

– Or by her husband at home, in awkward scenes that make full use of the extent of the set of the room, with the husband not only looking at his wife with an expression of trepidation, but wary of even getting too close to her.

Domestic scenes with the husband show him reluctant to make eye contact with his wife, only able to fleetingly look at her before having to leave the house.

Having established the motif of the look, the episode then uses it to convey the various forms that Christine’s ostracism takes, inviting the viewer to register the different types of look and to form associations between them, as in this scene of Christine being taken home.

(Clip 2: 40 seconds: Exterior of Christine arriving outside her home in a police car, expressions of two female neighbours, close-up of Christine’s face. Interior of waiting husband (Ian Thompson) looking out of window. Christine arrives indoors, husband looks at her with an uncertain expression, crash zoom on Christine’s face. Christine runs to husband, embraces him and sobs, observed from the staircase by her mother-in-law (Hazel Bainbridge) in silhouette, who then turns away.)

This scene shows three different types of look in immediate succession; the neighbours’ hostility;

the husband’s hesitancy;

and, shown in a rather sinister Hitchcockian way, the mother-in-law’s disapproval, where the viewer doesn’t even have to see her face to be aware of the look –

Again, the dialogue is insignificant.

Again, the dialogue is insignificant.

Only once in the episode is the convention of the look reversed, and Christine presented with her own opportunity to look and to judge. In a scene when the two plots of the drama come together, Christine identifies her assailant – the police arrange for her to wait outside the suspect’s workplace and pick him out. However, in order to be able to prove in court that Mrs. Lewis has recognized her assailant herself and not been led towards her decision, she has to be alone when she identifies him, sat inside a car and alerting the police by switching on the headlights.

So at the one moment when Christine is presented with the power to look herself, she is also presented as an isolated figure.

Christine’s final scene in the episode works retrospectively, finally giving the character voice to reflect on her treatment since the attack –

(Clip 3: Two minutes: Scene of Mr and Mrs Lewis in their living room. Husband drinks and makes half-hearted sympathetic conversation. Christine tells him that he is looking at her with “That look – the same as the others.” The husband then complains that everyone will be looking at both of them with the same look from now on, as he was the husband who let his wife be raped. Christine asks him if he has any idea what it feels like to be raped, and her husband complains that everybody always knew that she was the type and he’s going to be a laughing-stock from now on.)

This remarkably bleak and upsetting concluding scene makes explicit verbally what that has been implicit visually for the preceding fifty minutes, the notion of “the look”. Mrs. Lewis will be fated to remain an object of unwelcome fascination for as long as she stays in Broadstone, as a “two-headed monster” to be looked at, but not to be seen as a person.

That the drama ends in this way, with a verbal articulation of visual ideas, might seem on the face of it to support Kennedy-Martin’s contention, but my interpretation of how the episode functions dramatically is different. The programme has placed great trust in the viewer’s patience and intelligence in being able to follow a visual idea for fifty minutes without it having been signposted or made explicit, a dramaturgical decision unlikely to be made in a present-day equivalent to Hunters Walk. The programme has presented a character’s situation through showing, not telling.

So, to conclude, I hope that I’ve demonstrated how the narrative of studio drama could be communicated as much through visual nuances of performance as it was through dialogue, and I want to suggest that we should think of the studio form of drama as much in terms of the possibilities that it offered for storytelling, as its limitations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gambaccini, Paul and Taylor, Rod, Television’s Greatest Hits: Every hit television programme since 1960, London: Network Books, 1993.

Kennedy Martin, Troy, ‘Nats Go Home’, Encore, 48, 1964, pp.21-33.

Millet, Kate, Sita, London: Virago Press, 1977.

Mills, Brett (2011) ‘Invisible Television: The Television Programmes No-one Talks About Even Though Lots of People Watch Them’, Critical Studies in Television, 5 (1), 2011.

Pingback: Glance, gesture and inference in Hunters Walk (ITV/ATV 1973-76): Acting for multi-camera popular drama in the 1970s | Forgotten Television Drama