Written by Erika Delbecque, UMASCS Librarian, as part of the 2017 Being Human festival: Lost and Found.

The leaf on my desk was stained, torn in places, and fairly unremarkable. Unlike other loose leaves from the fifteenth century that I had been working on, which mostly contained standard texts that circulated widely at the time, the text proved difficult to identify. My secondary school Latin enabled me to, slowly, make some sense of the heavily abbreviated lines.

I read sentences such as

Feria iij. de sancto Augustino. et memoria sub silencio. de martiribus et de trinitate

On the third weekday, [hold a service] about Saint Augustine. And a remembrance in silence of the saints and the Trinity.

The Caxton leaf that was discovered at the University of Reading (detail)

It became clear that this was a page from a practical book aimed at clergy: an ordinal. Research into the publication history of this type of book led me to a version of the ordinal written by Clement Maydeston, a medieval priest from Middlesex. His text became the standard ordinal in the late fifteenth century.

However, the font and the layout of the text on the leaf did not match any known editions of Maydeston’s work. By chance, I read that an earlier version of the ordinal had been printed by William Caxton in 1477, which survived only in two fragments of eight damaged pages each. These had been discovered in the binding of a book in the library of the Grammar School at St Albans in 1858. Describing the pages, William Blades, the scholar who made the discovery, noted:

The lines are not spaced out to one length. A full page has 22 lines (cited in Wordsworth 1894)

The Caxton leaf that was discovered at the University of Reading

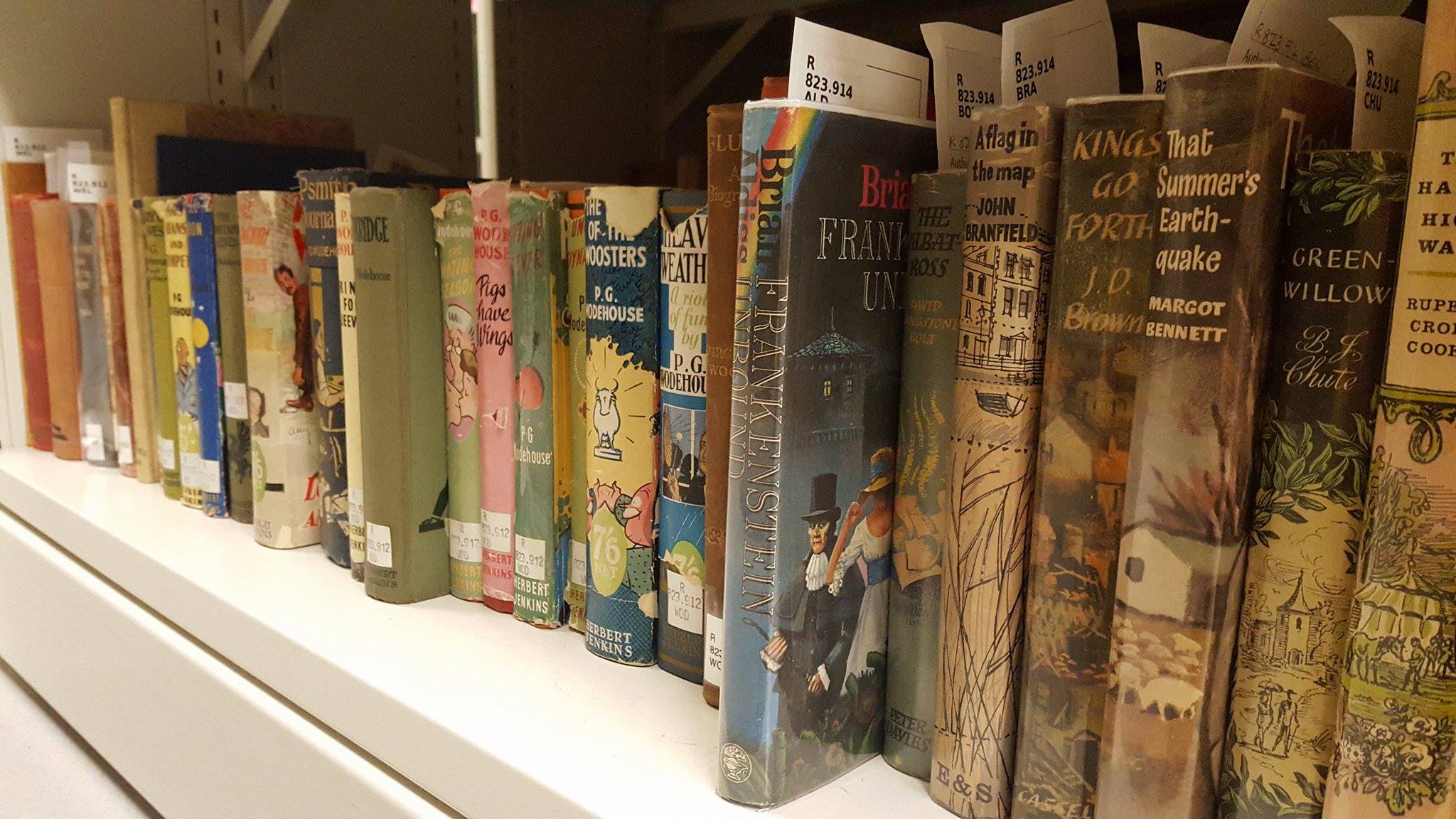

Sure enough, the leaf in my hands had 22 lines, which were not spaced out to one length. Could it be…? The surviving fragments that Blades had discovered, which are now kept at the British Library, are available digitally through Early English Books Online.

The font matched. The layout matched. The page measurements matched.

The unassuming leaf that had been in our collections for almost twenty years turned out to be a unique survivor from a long lost William Caxton book.

Late hym come to Westmonester

Having learned how to print in the Low Countries, Caxton arrived in London to set up the first British printing press about a year before this ordinal was printed. He was a shrewd businessman, seeking out texts to print that would appeal to a large audience. An ordinal would have been a safe bet in Catholic Britain: there was a steady demand for liturgical handbooks from the clergy.

To advertise his ordinal, Caxton printed notices that were pasted on walls and doors in London, in which he urged customers to head to his shop in Westminster to buy the book because it is “wel and truly correct” and “good chepe”. Incidentally, it is oldest surviving printed advertisement in the English language.

Advertisement for Sarum Pie [‘Ordinale ad usum Sarum’] ([Westminster: William Caxton, c.1476-7]) ©Bodleian Libraries

A perilous journey

What happened between the time when the freshly printed leaf left Caxton’s presses and the moment it was discovered in our collections over 500 years later? The leaf contains clues that offer tantalising glimpses into the journey it made before it ended up on our shelves.

Detail of the Caxton leaf showing the red paraph marks

The first of these are the red marks on the page, so-called “paraph marks” which indicate the start of new sections. Unlike the letters on the page these were not printed, but added by hand. Books from the fifteenth century were modelled on medieval manuscripts, and specialised scribes called “rubricators” would add page numbers and paraph marks in coloured ink. Although it was common for customers to take their printed book to a rubricator themselves, evidence from surviving books printed by Caxton suggests that he employed in-house rubricators in his workshop (Tokunaga, 2012). Their work would have turned our book into a finished product, ready to be sold in Caxton’s shop at the “almonesrye at the reed pale” in Westminster.

Detail of the Caxton leaf showing the offsets from a leather binding

At some point in the following centuries, its fortunes changed. The Reformation, which raged across Britain and the rest of Europe in the sixteenth century, eliminated the need for Catholic ordinals. Dark offsets from leather towards the edges of the leaf hint at what happened next: the leaf was folded and used to reinforce the cover of a later book. Rather than wasting new paper, which was a relatively expensive commodity at the time, bookbinders often recycled leaves from earlier documents for this purpose. So, we largely owe the survival of the Caxton leaf to the thriftiness of these craftsmen!

Portrait of William Caxton from a proof illustration to John Johnson’s ‘Typographia or the Printers Instructor’. 1824 ©British Museum

What happened next is shrouded in mystery. At one point, someone must have taken the leaf out of the binding, although it is unlikely that they realised its significance. The leaf may have changed hands several times, until the late typographer John Lewis purchased it as part of a collection of loose early printed leaves in the 1950s. Lewis suggests that these leaves may have slumbered in bindings of rare books at Cambridge University Library, until they were removed by a diligent sticky-fingered librarian:

A dozen years or so ago, I bought from a bookseller in Ipswich, Suffolk, an album compiled about the year 1820 by a Dr Lodge, sometime librarian to the University Library at Cambridge. […] As librarian to a great library, Dr Lodge’s opportunities for collecting pages from damaged books and packings from broken bindings were extensive (1990, pp. 9-10).

In this way, unbeknown to Lewis himself, a unique Caxton leaf made its way into his collection of historical examples of printing and graphic design. In 1997, this collection was purchased by the University of Reading, where it would sit on the shelves awaiting detailed cataloguing for the next twenty years.

Libraries within libraries

We will probably never know what detours and stops our Caxton leaf made on its five-century long journey from London to Reading via Cambridge and Ipswich. When I identified the leaf as an early example of Caxton’s printing, I realised that what I held in my hands was a unique witness of the introduction of what is perhaps the most significant invention of the modern age. This small, humble leaf has now assumed its rightful place amongst the treasures of our collection. Who knows what other treasures are lurking hidden in bindings on library shelves, libraries within libraries waiting to be discovered?

References

Lewis, John 1990, Printed Ephemera. 2nd ed, Woodbridge: Antique collectors’ club.

Wordsworth, Christopher (ed.) 1894, The Tracts of Clement Maydeston: With the Remains of Caxton’s Ordinale, London: Harrison and Sons, 1894.

Tokunaga, Satako 2012, Rubrication in Caxton’s early English books, c.1476–1478. Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 15.1 59-78.

For information on opening hours and how to find us, please see

For information on opening hours and how to find us, please see