This weekend we celebrate Nancy Astor’s birthday, said to be on the 19th May. But is there more to this birth date than meets the eye? Head of Archive Services Guy Baxter takes a closer look at the mystery surrounding Nancy Astor’s birth.

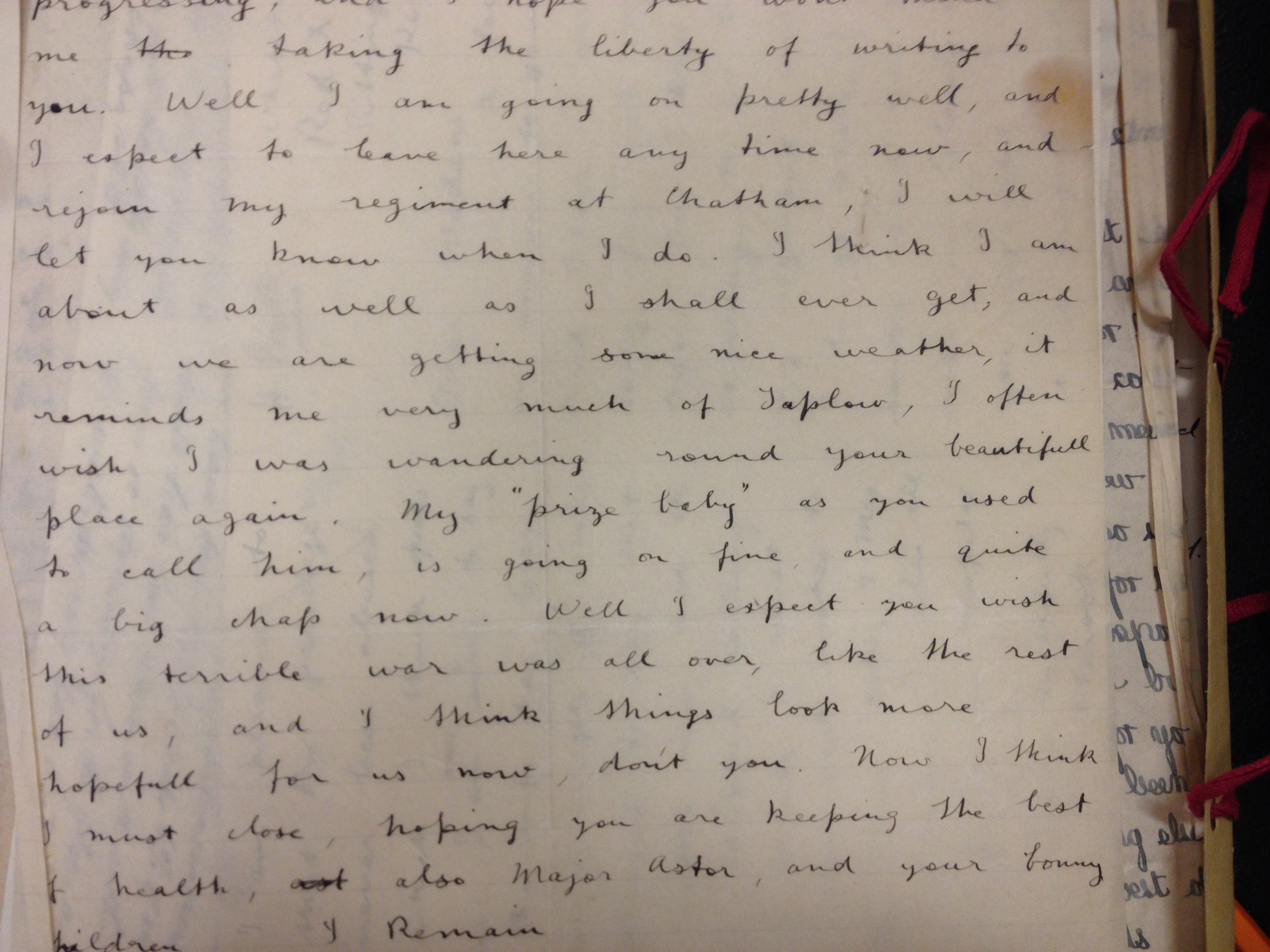

- A selection of the cards sent to Nancy Astor on her 80th Birthday. Nancy received hundreds of cards every year. But were they sent on the right date? (MS 1416/1/2)

The first female MP to take her seat in the British House of Commons, Nancy Astor was born (as Nancy Langhorne) in Danville, Virginia. But when exactly?

It is not unknown for celebrities to be coy about their age, but there was no such vanity from Nancy Astor. The mystery in this case surrounds not the year (1879) but the date of her birth. Stranger still, it was not until the publication of Adrian Fort’s extensively researched biography in 2012 that the mystery came to the attention of the public – or even specialists in the field.

Fort sums up the mystery thus: “It was at street level in the newly built house at Danville, in a room with dull green walls and a bare wooden floor, that Nancy was born on 30 January 1979 – although subsequently, and throughout her adult life, her birthday was, for no clearly stated reason, given as 19 May.” The biography is aimed at the general reader so, understandably, there is no footnote; I therefore approached the author and asked his source. What came back to me was a scan of Nancy Astor’s birth certificate extracted (with some difficulty, I gather) from the State authorities in Virginia.

The plot then thickens somewhat. Waldorf Astor (Nancy’s second husband) was born on 19 May 1879. So Nancy Astor, for much or her adult life and to the extent it confounded biographers and academics for years, seems to have adopted the birth date of her second husband.

Apart from scratching our heads, what should we do with such information? I suggest three things: we can speculate on the reasons; we can do more research, or at least bear this my

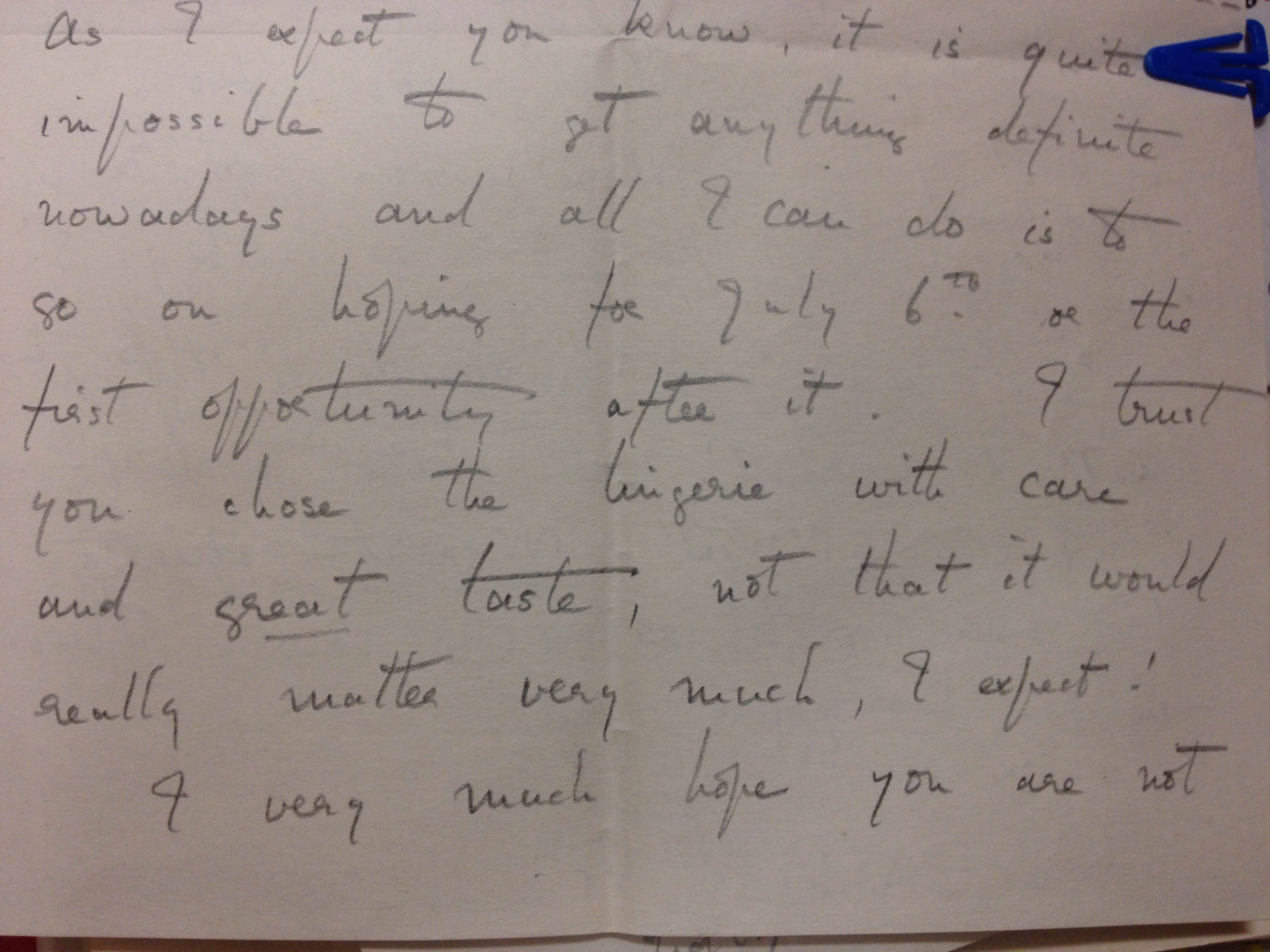

Nancy and Waldorf Astor. Was their shared birthday an elaborate in-joke? (MS 1416/1/6/94/10)

stery in mind while researching in the archives; and finally we might use this as a starting point to explore some wider implications and issues.

The speculation first. Is the Virginia record incorrect? There would seem to be no good reason to back-date a birth record, and it seems like an odd error to make. Having said that, the strange case of Ulysses Simpson Grant springs immediately to mind.

Born and raised as Hiram Ulysses Grant, he was the victim of an assumption made by the Congressman, Thomas Hamer, who nominated him to enrol as a student at West Point. A family friend, Hamer only knew him as Ulysses and inserted Grant’s mother’s maiden name (Simpson) into the register. The United States Army bureaucracy proved immovable and Grant, once he realised the error, was unable to change it. By the time he became the head of the U.S. military and 18th President of the United States, it may well have ceased to bother him, and it gave him the patriotic initials “U.S.” which proved a boon as his military career took off. So mistakes in an official record can be hard to change.

If the record is correct, then we must ask whether Nancy was aware that this was her birth date. Could her family have deceived her? Apart from the fact that no obvious reason springs to mind, neither this idea, nor that of an administrative mistake, explains the co-incidence with Waldorf’s birth date. Though it should be noted that the odds of two randomly selected people sharing a birth date are not outrageously long.

Perhaps Nancy and Waldorf decided to align their birthdays: possibly for convenience, possibly as an in-joke or an intimate secret. Given their wealth, sharing a birthday party can surely not have been a money-saving measure. Or is it possible that Nancy concealed her real birth date from Waldorf? Could the shared birthday have been a ploy in her courtship? As the son of one of the richest men in the world, he was quite a catch – was it worth a small lie to grab his attention?

This must all remain as speculation until more evidence emerges. Neither Fort nor any previous biographers found any mention of it in Nancy or Waldorf’s personal correspondence, though this is very extensive. Nancy’s correspondence with her American relatives is more recently available and has been less used by researchers. Deceit, mistake or shared joke, it may well have been referred to in a deliberately obscure manner. Seekers of the truth will find the Special Collections Reading Room a pleasant and friendly environment in which to seek out needles from haystacks. As far as I know, Waldorf Astor’s birth certificate has not been checked: could there be a further twist in the tale?

So to the final, and more serious word about this. Just as his mistaken identity probably mattered little to Grant, especially as he rose to prominence, so Nancy Astor’s birthday must have been of little real

Cliveden House in Buckinghamshire, family home of Waldorf and Nancy Astor (MS 1616/2/6/94/3)

significance in her life or livelihood. The official record is of minimal practical benefit for the rich and famous. But as the Windrush scandal has brought into sharp focus, for many citizens the possession of verifiable identity documents can be a critical matter. It is not for nothing that patients are identified not just by their name but also by their date of birth: even then, horrific mistakes can occur.

Windrush is not the first time that the quality of the data recorded by the state to identify individuals has been questioned: Dame Janet Smith’s third report as part of the Shipman Inquiry – that looking at Death Certification – noted: “The information received by registrars forms the basis of an important public record that is widely used for statistical and research purposes. It is vital that it is recorded meticulously and accurately.” It was not until 50 years after her death that the search for documentary evidence of Nancy Astor’s birth began. Most citizens rely on the integrity of such systems in their lifetimes: for the most vulnerable, this can be crucial.

So let us toast Nancy Astor, whether it’s her birthday or not, for reminding us of the value of the written record. Or as the Universal Declaration on Archives puts it, “the vital necessity of archives for supporting business efficiency, accountability and transparency, for protecting citizens rights, for establishing individual and collective memory, for understanding the past, and for documenting the present to guide future actions”.

Are you intrigued to do your own research on this mystery? Or just interested to know more about Nancy Astor? Find out more about the Papers of Nancy Astor held at Special Collections here. For further enquiries, or to request access, email specialcollections@reading.ac.uk.