Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

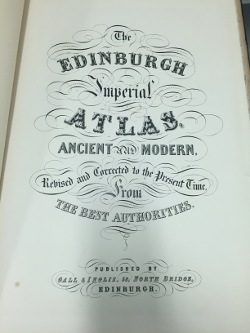

The ‘Edinburgh Imperial Atlas: Ancient and Modern’ (1859) [Overstone – shelf large 34I/10] is a beautiful collection of maps developed from, what the publishers Gall and Inglis describe as, ‘The Best Authorities.’ Unfortunately, very little information is given as to who these authorities may be or which dates the historical maps reflect– indeed only two are named: Gerard Mercator and Strabo.

Strabo (c.64BCE – 21 CE) was a Greek geographer and historian whose work ‘Geography’ diligently describes “the whole range of peoples and countries known to both Greeks and Romans during the reign of Augustus,”(Lasserre.) Strabo drew on his own travel experiences as well as the first-hand accounts of explorers such as Polybius and Poseidonius, and earlier geographers including, Artemidorus, whose book describing a voyage around the world provided Strabo, “with a description of the coasts and thus of the shape and size of countries,” (Lasserre).

Gerard Mercator (1512-1594) was a Flemish cartographer who not only introduced the term ‘atlas’ for a collection of maps but also created “one of the most influential depictions of the globe,” (Molloy, 2015), in 1569, known as the ‘Mercator Projection’. The map is often still used today; even Google Maps uses a close variant! (Molloy, 2015)

Mercator’s projection was highly useful for sailors and widely used for navigation charts as, “any straight line on a Mercator-projection map is a line of constant true bearing that enables a navigator to plot a straight-line course,” (Britannica.) However, while the map is an excellent navigational tool, the inaccurate scale of various landmasses make it less helpful as a general map of the world. For example, Greenland is particularly distorted, appearing to be larger in size than South America or Africa. (Molloy, 2015; Britannica)

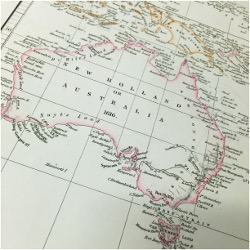

Although the remaining maps are without their creator’s name tags, they are beautifully rendered and contain a fascinating insight to the historical geography of the time. I particularly love the details on this map which show the longest rivers and tallest mountains in the Western Hemisphere:

Based on this newspaper clipping from ‘The Glasgow Herald’ in December 1851, an earlier edition of the ‘Edinburgh Imperial Atlas’ was marketed as an educational resource. These comparative maps of

ancient and modern geography were first compiled for classroom use by French Jesuit Phillipe Briet in

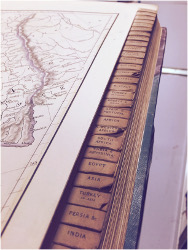

the mid-seventeenth century (Goffart, 2003.) They usually mirrored the a Ptolemaic prototype, following the ancient map-makers’ focus on showing the outlines of different regions rather than providing glimpses of historical moments, (Goffart, 2003.) The ‘Edinburgh Imperial Atlas’ is no different with regions being highlighted with beautiful hand-colouring.

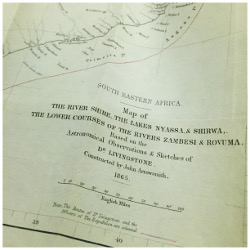

A particularly interesting feature of the colouring of this Atlas is the

effect of the pale green colour on the paper. Below is the reverse side of the map displaying Strabo’s view of the world. This effect is caused by oxidation of the copper acetate used to create the green pigment

‘verdegris’ (Greek Green) and is usually a sign that the colouring is original and was applied when the map was printed. (Meijer, 2008)

In his creation of a special collection of ancient maps in the late sixteenth century, cartographer Abraham Ortelius declared,“historiae oculus geographia, “geography (is) the eye of history,”” (Goffart, 2003) and in collections such as the ‘Edinburgh Imperial Atlas’ it is certainly possible to see the historical development of our understanding of the shape of our world.

Sources and Further Reading:

Goffart, Walter. Historical Atlases : The First Three Hundred Years, 1570-1870. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 2003. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 2 March 2016.

Lasserre François – Britannica: Strabo

The Glasgow Herald – 22 December 1851

The Edinburgh Imperial Atlas – digitisation

Britannica: Mercator Projection

Meijer, Boudewijn (2008) Antique Maps – Recognising the difference between old and modern colouring