Summary of Findings

In this page you will find a breakdown of our sample and further down the page a summary of our findings. For detailed findings per area of interest, please click on the Results menu in the top banner and go to your area of interest.

Methods and participants

Our sample consisted of 76 families/carers or foster carers and 63 practitioners working in education or social care for children listed as “vulnerable” during the COVID-19 outbreak. The sample was sourced from the South and South West of England between April-July 2020. The e-surveys included 25 and 21 questions respectively exploring the views of respondents on aspects relevant to distance learning, wellbeing, mental health during the outbreak and safeguarding as well as reopening of schools after the outbreak.

Figure 1 shows the gender of participants by group. It is noticeable that most respondents were female.

Figure 1

Gender by Group of Participants

Tables 1 and 2 present the roles in the sample by group. Percentages per row represent the proportion of participants selecting each option in the total of participants in their group (Practitioners N=63, Families N=76). For cohesiveness, in this report, we will refer to the two groups as ‘practitioners’ and ‘families’.

Table 1

Roles of Practitioners

| Roles | Raw Number | % |

| Head or Deputy of school/setting/institution | 12 | 19 |

| Manager of a team | 10 | 15.9 |

| SENCo/aspiring SENCo/Inclusion Lead or Deputy | 23 | 36.5 |

| Teacher | 21 | 33.3 |

| Teaching Assistant | 6 | 9.5 |

| Other staff in education (LAs included) | 8 | 12.7 |

| Social worker | 1 | 1.6 |

| Other staff in social care or children’s services (LAs included) | 3 | 4.8 |

| NA | 1 | 1.6 |

| Total | 85 | NA |

Note. Participants could select multiple options resulting in percentages not adding up to 100%.

Table 2

Roles of Family Members

| Roles | Raw Number | % |

| a parent/carer | 73 | 96.1 |

| a foster carer | 3 | 3.9 |

| 76 | 100 |

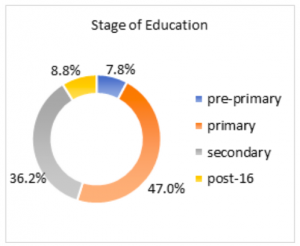

Figure 2 shows the age range of children by stage of education for practitioners and age group for families. It is noticeable that most practitioners were working with children in primary or secondary education and most families had children between 4 and 16 years old.

Figure 2

Stage of Education for Practitioners and Children’s Age Range for Families

Note. Answers of practitioners are shown on the left and of families on the right.

Practitioners responded about different types of schooling as shown in Table 3 below. Respondents could select multiple choices. Raw numbers and percentages represent popularity of each type of schooling.

Table 3

Types of Schooling for Practitioners

| Types of Schooling | Raw Number | % |

| Mainstream school | 21 | 24.4 |

| Special school | 9 | 10.5 |

| Local Authority maintained school | 23 | 26.7 |

| Part of multi-academy trust | 17 | 19.7 |

| Independent school | 2 | 2.3 |

| Registered childcare provider | 2 | 2.3 |

| FE, colleges, post-16 institution | 2 | 2.3 |

| Home–schooling | 2 | 2.3 |

| LA and social care | 5 | 5.8 |

| Alternative provision | 3 | 3.4 |

| Total | 86 | 100 |

Participants responded about groups of children they worked with as presented in Table 4. Percentages per row represent the proportion of participants selecting each option in the total of participants in their group (Practitioners N=63, Families N=76). It is noticeable that higher percentages in both groups worked or cared for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND). In the group of participants, high percentages were also accrued for children with and in-need/protection plan, looked after children, assessed as otherwise vulnerable during the COVID-19 outbreak, and children of key-workers. About one third of practitioners also worked with children that had English as an Additional Language (EAL).

Table 4

Groups of Children per Sample Group

| Group | Practitioners | Families | ||

| Raw Number | % | Raw Number | % | |

| SEND | 51 | 81 | 68 | 89.5 |

| In–need/protection plan | 41 | 65.1 | 6 | 7.9 |

| Looked-after | 38 | 60.3 | 4 | 5.3 |

| EAL | 25 | 39.7 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Refugee/unaccompanied minor | 5 | 7.9 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Disadvantaged background | 34 | 54 | 6 | 7.9 |

| Assessed as otherwise “vulnerable” | 39 | 61.9 | 17 | 22.4 |

| Children of keyworkers | 38 | 60.3 | 5 | 6.6 |

| Other | 4 | 6.3 | 3 | 3.9 |

| Total | 275 | NA | 112 | NA |

Note. Participants could select multiple options resulting in percentages not adding up to 100%.

We explored further the types of SEND of learners in our sample. Many practitioners and families worked or cared for children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (83.6% of practitioners working with SEND, 67.1% of families of children with SEND). Other types of SEND that accrued high percentages were Social, Emotional and/or Mental Health Difficulties (77% of practitioners and 49.3% of families), Specific Learning Difficulty (e.g., dyslexia, dyscalculia) (62.3% of practitioners and 27.4% of families) and Speech, Language and Communication Difficulties (59% of practitioners and 41.1% of families).

Summary of findings

In the following sections, there is a summary of main findings relevant to practitioners and families’ changes in practices and views in response to ‘vulnerable’ children’s needs during the COVID-19 outbreak. Responses of the two groups are compared by theme.

1) Practices and views of education during the COVID-19 outbreak:

We asked practitioners and families if the lockdown during the COVID-19 outbreak changed their workload, responsibilities, priorities, and views of education. Working patterns for practitioners varied from 1 to 5 days a week combining work at home and in setting. Additional responsibilities during the outbreak included coordinating distance learning/home-schooling and responsibilities relevant to children’s wellbeing as well as administrative tasks to support provision for children, training and mentoring of colleagues. Educational settings prioritised communicating with stakeholders, online learning, safeguarding, admin, wellbeing, and their own Continuous Professional Development (CPD). A high percentage of practitioners and families prioritised wellbeing and safeguarding over learning progress to meet the exceptional circumstances of the lockdown. Qualitative responses discussed how practices changed based on these new priorities, and what reasonable adjustments needed to be made to respond to the needs of ‘vulnerable’ children during the outbreak. Finally, practitioners and families reflected on the purpose of education beyond academic achievement and emphasised opportunities to go beyond curriculum mandates, to explore alternative resources and to appreciate the value of developing social and life skills.

Notions of vulnerability:

Overall, practitioners and families seemed to feel that during the COVID-19 outbreak the children they are responsible for were more vulnerable than the general student population. The two groups of participants showed the opposite picture when asked whether they felt vulnerable themselves with practitioners feeling overall less vulnerable than families. We asked about two main reasons for a rise in concerns during the outbreak, safety from COVID-19 and isolation due to the lockdown. Regarding the former, practitioners appeared more worried than families. Finally, overall, both groups considered that isolation during the COVID-19 lockdown can have a negative impact on mental health.

For detailed findings go to page: https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/vunerable-children-covid-19/practices-during-covid-19/

2) Learning:

Distance learning and home-schooling:

Overall, distance learning and home-schooling were used interchangeably by practitioners, although it was mentioned in qualitative responses that home-schooling during COVID-19 may differ from the way children were home-schooled before the outbreak. Practitioners and families seemed to agree that a high proportion of their children started home-schooling due to the outbreak. According to both groups’ responses, the person responsible for distance learning was a parent or a teaching staff from the child’s setting. Most families reported that their children depended on an adult to complete the learning tasks, but this varied from being 100% dependent to 100% independent. The two groups had similar views on the impact of learning practices during the outbreak on their opinion about feasibility of home-schooling and outlined what they perceived as advantages and disadvantages of learning at home. Practitioners reported keeping in regular contact with families during the outbreak and monitoring attendance of learners still attending school. Both groups discussed completing and returning learner’s homework during the lockdown. Finally, they overall agreed that distance learning regularly or frequently meant digital learning in their conversations during the lockdown.

Digital learning:

On the topic of digital learning, the majority of practitioners reported seeing an increase in the use of digital resources over non-digital resources. The two groups of participants seemed to agree on their views regarding digital versus non-digital resources. About 1/3 of both groups said practices during the lockdown resulted in them changing their views on digital versus non-digital learning. Qualitative comments highlighted advantages and disadvantages of the two forms of learning. Although a high proportion of both groups reported being confident in finding and using digital learning resources, there were differences in the level of confidence of each group and the impact that learning practices during the lockdown had on the two groups’ rise of confidence. Practitioners reported having extra training on different aspects of using digital learning resources and families discussed guidance received from their child’s setting or their Local Authority on how to support digital learning at home. For about 50% of both groups there was an impact of learning practices during the lockdown on sourcing and evaluating learning materials. Their qualitative comments discuss accessibility, monitoring effectiveness of materials and broadening their repertoire of places to source learning resources. Responses of practitioners and families showed a difference on the theme of sharing learning materials and collaborating with others during the outbreak, with a higher percentage of practitioners interacting with each other to share materials and skills. Qualitative responses from both groups discussed changes in their practice in relation to supporting digital learning, difficulties that they faced along the way and ways to overcome them.

For detailed findings go to page: https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/vunerable-children-covid-19/learning-2/

3) Wellbeing, Mental Health and Safeguarding

Accessing support:

We asked participants about provision for the wellbeing and mental health of vulnerable children and themselves during the outbreak. Practitioners’ responses showed that over half of the settings were able to respond to their vulnerable learners’ needs without support from volunteers. Practitioners and families reported volunteering outside work or home to support settings and community members in need of support during the outbreak according to their skills and availability. The two groups illustrated a different picture when asked about the support they were giving or receiving from others. A high proportion of practitioners reported having regular or frequent support from colleagues on wellbeing and mental health of students and staff in settings. The percentage of families collaborating with other families for support was significantly lower. Practitioners were more confident about where to go for help to support wellbeing and mental health, while more than one third of the group of families were sure about where to go less often or never. A similar picture was reflected by families’ responses about accessing support from charities relevant to their child’s needs.

Sense of community and interaction between practitioners and families:

Overall, practitioners appeared to experience a new sense of community during the COVID-19 outbreak more than families. However, similar percentages from the two groups agreed that this new sense is a natural human response to situations of crisis and about one third of the whole sample were indecisive. When asked specifically about interactions between stakeholders (school, Local Authority and family of the child), significantly more practitioners than families reported regular or frequent interactions. Exchanging information about the child’s progress, wellbeing, mental health, and health was the most popular purpose of interaction according to both groups of participants. They also discussed other focal points of their interaction during the outbreak relevant to learning, wellbeing and smoother transition back to formal schooling.

For detailed findings go to page: https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/vunerable-children-covid-19/wellbeing-and-mental-health-2/

4) Meeting vulnerable children’s needs:

Overall, about half of the sample felt that the lockdown affected ‘vulnerable’ children, e.g., increased anxiety levels, which made them more alert about their needs, while the other half reported being already aware of these. When asked about any concerns they had about meeting the children’s needs during the outbreak, about half of both groups were regularly or frequently worried about it having considered available resources, costs, staff, and priorities during the outbreak. We got mixed responses in relation to the effect that practices during the outbreak had on their views on meeting their children’s learning, wellbeing, safeguarding, medical/health needs reflecting the variability in the personal experience they had. On the theme of contribution of new technologies to meeting the needs of their children during the outbreak, the views of practitioners and families overall showed a similar picture. More than half of the whole sample agreed that new technologies contributed a lot to interacting with others, keeping optimistic, supporting each other. About the same proportion of each group reported having gained confidence in the effectiveness of new technologies to support their children’s needs. Practitioners appeared to be more on board with the idea of using social media during and after the lockdown to meet learner’s needs than families. It is worth noticing that about a third of the sample remained indecisive about the effectiveness of contribution of new technologies to meeting their children’s needs during and after the lockdown. Qualitative responses shed more light in participants’ views.

For detailed findings go to page: https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/vunerable-children-covid-19/meeting-the-childrens-needs/

5) Life after peak and reopening schools

The notion of ‘New normality’ appeared to be a difficult concept to imagine for more than half the sample while about ¼ of the sample remained indecisive about whether it would be different from life before the outbreak. The two groups seemed to trust the same sources of information during the outbreak: mostly journalism, government guidance and news summaries from their senior management team. For families, social media were also one of the main sources of information. In relation to reopening schools, about half of practitioners and families were worried about the children’s transition to formal schooling. Qualitative responses discussed their main worries, which were relevant to the time needed for smooth transition, the social challenges of re-joining formal education and safety from COVID-19. Practitioners and families agreed that safe reopening is not yet possible and that the voices of stakeholders should be heard when it comes to reopening.

For detailed findings go to page: https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/vunerable-children-covid-19/reopening-schools-2/

If you would like to contribute your questions, please go to: https://reading.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/have-your-say