We originally hoped to incorporate some animated content and film into the exhibition, which for various practical reasons was not possible. As such, I thought I’d expand on some of these ideas and provide links to some interesting material here instead.

The arrival of photography in the nineteenth century led to realistic depictions of animal movement. The most famous example of this transition came in the form of work by visual pioneer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904). He used the camera to take different series of single frame stills that represented sequences of animals and people in motion. These images revealed how things actually moved. The stills he took have been re-animated by modern scholars.

Animated sequence of a race horse galloping. Photos taken by Eadweard Muybridge (died 1904), first published in 1887 at Philadelphia (Animal Locomotion).

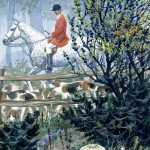

Despite these significant advances, Charles Tunnicliffe clearly opted to study specimens directly and to sketch from life. These observations—especially of birds—shaped his own ability to portray the animal world. The huntsman illustration at the heart of the exhibition also captured motion in its own way, operating much like a single frame from an animated film.

Although unconnected in life, Tunnicliffe actually had much in common with Walt Disney (1901-1966). Born just days apart at the very beginning of 1901, they both worked as commercial illustrators, later producing popular art for children and adults alike. Whilst the former sought to entertain and the latter to educate, their work shared a degree of captivation with animal movement.

Just as Tunnicliffe explored hunting through ‘Tarka the Otter’ and his illustrative work for Ladybird, visual and animated representations of hunting also featured in several Disney productions, first appearing in the 1938 cartoon The Fox Hunt.

The most successful hunting sequence of Disney’s lifetime and career was probably the blend of live action and animation in Mary Poppins. Based on the children’s books by Pamela Lyndon Travers, this film hit the screens in 1964, the heyday of Ladybird.

Far from offering a neutral depiction of fox hunting, Disney’s satirical and humourous sequences portrayed it as something to be ridiculed and something for the British upper classes. Nevertheless, in their own way these sequences helped to add to the sense that it was somehow quintessentially English and inherently part of the landscape and rural life in question.

As well as delving into ideas of animation and how animal movement was captured by Tunnicliffe and his contemporaries, we briefly explored another bit of film, this time of a more biographical nature. Tunnicliffe himself seems to have been the subject of a 1981 BBC Wales television documentary called True to Nature. We have yet to track down a copy of this documentary. If anyone remembers it we’d love to hear from you.