[Image of an oblique profile of an ancient marble bust of a soldier in a plumed helmet,

thought to be Spartan General Leonidas, Sparta Museum].

Author: Dr. James Lloyd-Jones. Edits: Bunny Waring.

Date: 28th May 2021.

Sparta. What image is conjured in your mind? The ancient Spartans are often seen as the venerated, the heroes of Thermopylae. But they are also the villains, the enslavers of the helots, and the supporters of eugenics. In fact, the contemporary view of the ancient Spartans as heroic macho warriors is so widespread, thanks to 300, that when we explore the Spartans in more detail, the image that appears can seem surprisingly complex and uncomfortable.

[Image showing a scenic view of the Spartan theatre as stone remains with the Taygetos mountain range in the background].

Not only do we have to deal with the complications of modern interpretations of Sparta (some of them appropriated by political extremists), but we need to tackle the complications of ancient interpretations too. With the lack of any meaningful historical narratives written by a Spartan, the evidence from Sparta itself can be bitty and difficult to interpret. For example, the Classical agora remains unexcavated, and many inscriptions are still untranslated.

The major accounts about the Spartans that do survive are written by non-Spartans such as Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Aristotle, Pausanias, and Plutarch. They come with their own interpretative issues too. Thucydides fought, and lost, against the Spartans. Xenophon was buddies with a Spartan king. Plutarch wrote nearly half a millennium after the period of Spartan hegemony and dealt in writing engaging biographies. And this is all before we get to the historiographical phenomenon known as the ‘Spartan Mirage’. We are not the only generation for whom the image of the Spartans could be decidedly one-dimensional, over-exaggerated, or dowsed in political and philosophical motives. These are all some of the juicy topics that we sink our teeth into in the third-year module “Ancient Sparta” (CL3SP for those who want to look it up).

[Image of Caitlin’s map showing the Mediterranean with marked estimated trade routes from Port Gytheion].

Studying the Spartans can be an interesting exercise in a world with increasingly complicated sources of opinions, facts, and fictions dressed as facts. So, for one of our assessments, I decided that students might benefit from a digital project that would allow them to explore a facet of Sparta that might appeal to, and be surprising for, a general audience. It also presented an opportunity to think about how we present evidence, and the importance of geography in understanding Sparta, in the form of networks, findspots, and battle sites.

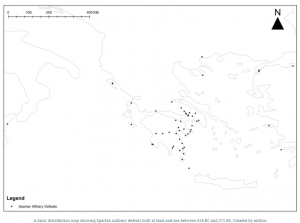

[Image showing a scatter map produced by student Alfie to show patterns of spartan military defeats at land and sea between 659 – 371 BCE].

The software that we used is ArcGIS StoryMaps, and you can view some of the work that the students created in the links provided. I was really impressed across the board with the work that was turned in, especially under the trying circumstances of COVID. The examples given here represent the broad spread of topics that everyone covered. The topics range from analyses of Spartan military capabilities to helot revolts, Spartan festivals, votives, trade, colonies, and more. Each of the stories presents a compelling case for taking a more nuanced approach when we ask the question “Who were the Spartans?” and I hope that you will find something of interest in each, I know I did!

Lydia’s “The Karneia: Festival or training camp?”

Robert’s “The Best Soldiers in the World.”

Eleanor’s “An Insight into Spartan Religious Cults and Sanctuaries.”

Alfie’s “Just How Invincible Was Sparta?”

Katie’s “Motives Behind the Votives.”

Daniel’s “The impact of the Helot Revolts on Sparta.”

Katy’s “Revels and Raves: Religious festivals and celebrations in Ancient Sparta.”

Jack’s “Sparta the colonizer: Was Taras really her only colony?”

Caitlin’s “A Crack in the Spartan Trade: The Journey of Laconian Pottery.”

The “Ancient Sparta” module focused on a series of lectures and seminars, as well as some practical sessions on how to use ArcGIS StoryMaps. There was a lively movie night where we got together to watch 300 (meme competition included), as well as an introduction to some of the archaeological material from Sparta in the Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology at Reading. Finally, we were very grateful to have additional video introductions from colleagues, providing the students with some alternative viewpoints and expertise. Many thanks once again to Paul Chirstesen, Stephen Hodkinson, Tyler-Jo Smith, and Paul Cartledge for their generosity of time and knowledge.

All being well, the module is due to run next year too, when, hopefully, we might be able to do some object-handling in the Ure Museum too. There’s something quite special about being up close to an object that a Spartan dedicated in a sanctuary over 2500 years ago.

[Image of three, small metal objects thought to be cult votives made by Spartans].