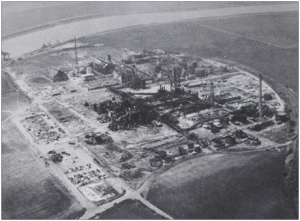

Images from Inquiry into Disaster at Nypro (UK) Ltd, Flixborough on 1/6/1974 (Official Report),via National Archive TS 84/37/1

“He [a senior HSE figure] put his hand up and said, ‘no, no, no, stop my boy, stop…that’s worker safety. That’s a dead volcano’, he said. ‘The live volcano is public safety. That is what’s going to energise everyone’.” [R. Bibbings interview, para.19]

One of the most pronounced shifts to have taken place in the last fifty years of health and safety regulation has been a movement towards recognising workplace risks that affect the general public. It is probably fair to say that the earliest eras of health and safety provision did not look beyond the factory or workshop in terms of their scope; indeed, most of the Factories Acts were explicitly limited in terms of the types of workplaces and industries in which they applied. But health and safety today is something that is understood as encompassing all areas of human activity, from education, to recreation, to work, to the use of public space. For many people, this ‘creep’ of health and safety into all areas of life is one of the key reasons for questioning the legitimacy of the law, and negative media coverage of health and safety does place an emphasis on the social, rather than the workplace, aspect of the issue. So when, and how, did this shift occur?

A review of the historical material suggests that the ‘public’ element was relatively little discussed before the 1970s, even in the aftermath of major events like Aberfan (which were seen as ‘public safety’ rather than ‘health and safety’ issues). The turning points appear to be twofold. While the Offices, Shops, and Railway Premises Act 1963 had broadened the scope of the workplaces in which health and safety risks were recognised, it was the 1974 Health and Safety at Work Act s.3 which turned attention to ‘public’ safety risks. This had been introduced in part because of the Flixborough explosion in 1974, which showed the potential of high-hazard risks to ‘cross the factory fence’ and affect local communities. Even then, however, the potential of this extension of coverage was not really appreciated or recognised – policy observers from the time have confirmed that, in the words of a former civil servant (and HSE Director-General):

“Robens did envisage that there would be some limited duties towards the public. But…at the time when the Act was going through, I don’t think that the very extensive ways in which public health and safety have come into play was envisaged.” [J. Bacon interview, para.23]

The second turning point was the mid-1980s, when three factors coincided to make public opinion a key player in regulatory thinking. A combination of the politicisation of issues of regulation and government intervention (particularly by the EC) by the Thatcher governments, a series of major disasters affecting the public and workers between 1987-9 (including the Herald of Free Enterprise and Marchioness sinkings, Piper Alpha, Hillsborough, and the Clapham rail crash), and HSE’s efforts to account for growing concern over major hazard sites (mainly nuclear power, and especially post-Chernobyl) as part of their new Tolerability of Risk Framework (1988) meant that suddenly, what the man in the street thought mattered a great deal more than it had in the past. Not only was more evidence then gathered about public opinion, but the balancing approach to be adopted became more explicit. While the initial assessments of both tolerability and preference looked at high-hazard issues, the legislative and policy framework that was created was soon providing a basis for judgements about an ever-widening array of sectors and issues.

In this way, the new focus on principled, evidence-led decision-making, coupled with the ability of s.3 HSWA to apply to people outside the workplace, would change the face of health and safety regulation forever. It remains an irony that the movement towards applying the law to ‘crazy’ cases like so-called bans on playing conkers in schools, was driven in part by the need to respond to some of the most hazardous workplace dangers imaginable, and a desire for greater rationality.