HISTORY

Sputnik Magazine was published monthly by the Soviet press agency Novosti from 1967 until 1991. Sputnik provided a digest of the Soviet press for international readers; it was available in several languages and sold in socialist and capitalist countries around the world.

The magazine presented topics relating to politics, science, and culture as well as the society of the Soviet Union. Novosti wanted to promote a positive, modern image of the socialist development in the Soviet Union internationally. The magazine’s name reflects this objective as it refers to the first artificial earth satellite, which was launched by the Soviet Union in 1957. As a means of promoting socialism Soviet style, Sputnik disseminated socialist propaganda which many readers in the socialist countries dismissed as indoctrination. However, with changes in Soviet policies in the 1980s, the magazine became a source of sought-after information and discussion.

SPUTNIK IN THE 1980s

When Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985 (until 1991), he promoted the new ideals of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) as approaches to a reformed socialism.

Perestroika/Glasnost

Perestroika was a political concept (1980 -1991) within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the 1980s, the economy in the USSR was crumbling, which resulted in poor living conditions, environmental problems, political disengagement, and disintegration of society. Gorbachev pursued a new approach to tackle the problems, believing that more openness in discussing problems would initiate a democratization and consequently engagement of people in much needed reforms. This included more freedom of speech and less censorship for the media and opposition groups either political or religious. These political changes were reflected in Sputnik magazine, which became a means of promoting and disseminating the new course in the Soviet Union internationally.

Perestroika was a political concept (1980 -1991) within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the 1980s, the economy in the USSR was crumbling, which resulted in poor living conditions, environmental problems, political disengagement, and disintegration of society. Gorbachev pursued a new approach to tackle the problems, believing that more openness in discussing problems would initiate a democratization and consequently engagement of people in much needed reforms. This included more freedom of speech and less censorship for the media and opposition groups either political or religious. These political changes were reflected in Sputnik magazine, which became a means of promoting and disseminating the new course in the Soviet Union internationally.

In his column, the chief editor of the magazine promotes reforms as renewal: ‘Perestroika bedeutet Erneuerung’.

“Die Perestroika ist ein Abschnitt im Leben unserer Gesellschaft, da sich ein jeder aktiv an den bei uns vor sich gehenden Umwandlungen beteiligen kann.”

(“Perestroika is a stage in the life of our society when everyone can actively participate in the transformations that are going on in our country.”)

Initiative, original ideas, and innovative thinking were celebrated as means of a renewal from below.

‘Mehr Demokratie – Aber Wie?’ (‘More Democracy – But How?’) was the central question of the issue.

SPUTNIK 6/1988

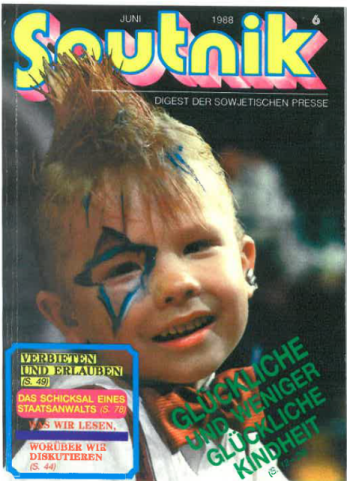

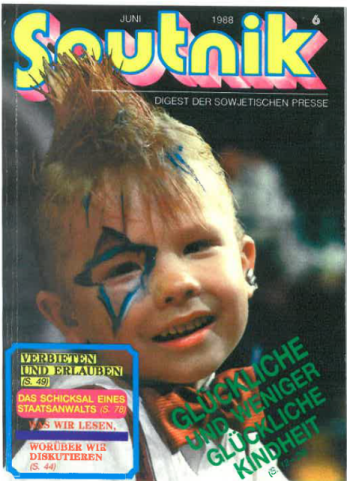

The June issue from the end of the 1980s reflects the political transformation in the Soviet Union. It compiles articles critical of social, political, and economic developments and endorses non-conformity and free speech. The front cover of the issue shows a young punk, an example of openness and tolerance of individuality, in this case of a subculture. The acceptance of other groups or subcultures who did not follow ‘the socialist norm’ is here seen as a progressive step towards reform.

The June issue from the end of the 1980s reflects the political transformation in the Soviet Union. It compiles articles critical of social, political, and economic developments and endorses non-conformity and free speech. The front cover of the issue shows a young punk, an example of openness and tolerance of individuality, in this case of a subculture. The acceptance of other groups or subcultures who did not follow ‘the socialist norm’ is here seen as a progressive step towards reform.

Children are a particular focus of the issue. As symbols of a society’s future, their situation is seen to reflect the Soviet Union’s perspective. An article titled ‘Was ist aus unserer Güte geworden?’ (‘What has become of our Kindness?’) is exemplary of the criticism of society’s failures. It discusses mothers [not fathers!] who light-heartedly give their children away or leave them in state care in order to work and pursue a career or simply have an easier life. The article stresses the loneliness and sorrow of the abandoned children.

“Die Mutter hat noch mit der Hand gewinkt, nun würde sie bald am Ende des Korridors verschwinden. Es würde an seine Mutter denken, wie es ihr so ginge, was sie morgen tat […] denn es liebte seine Mutter und glaubte fest daran, dass sie früher oder später zusammen sein würden […]”

(“The mother waved goodbye, now she would soon disappear at the end of the corridor. The girl would think of its mother, how she was, what she would do tomorrow […] for it loved its mother and firmly believed that sooner or later they would be together […]”)

Vehemently criticising the denial of a proper homes and family, the article points to a society that has become cold, careless, and disinterested in human values.

SPUTNIK IN EAST GERMANY

East Germany (GDR) faced problems in the 1980s similar to those of the Soviet Union. Under Erich Honecker as General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party (1971-89), GDR society suffered not just rapid economic decline, but stagnated politically and disintegrated. Unlike Gorbachev, Honecker refused to implement changes and even in the face of growing protest he pleaded for communism to remain unchanged. Ironically, it was the development in the Soviet Union with Gorbachev as its icon which inspired protest in East Germany. For the first time in post-war Europe, a Soviet leader became a political star celebrated by the masses who had until then seen the Soviet Union as oppressor. For the first time, too, people queued to buy Sputnik and found it an inspiring read. As the East German leadership feared loss of control, films, books, and newspapers from the Soviet Union were for the first time in East German history banned in order to contain the call for freedom. Sputnik magazine was banned on 18 November 1988; one year later, on 9 November 1989, the Berlin Wall had been brought down by popular protest and Sputnik was sold again.

Amy Peaurt, BA German and Spanish

Heimatkunde 3

Heimatkunde 3 The book opens with large images of Erich Honecker, General Secretary of the SED, the Television Tower and the city council building in the GDR, and captions explaining what each image is.

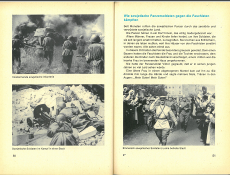

The book opens with large images of Erich Honecker, General Secretary of the SED, the Television Tower and the city council building in the GDR, and captions explaining what each image is. The narrative of Fascists vs. Antifascists is described, and the book tells the story of the antifascists being taken away to concentration camps. Readers also learn that Ernst Thälmann, the leader of the Communist Party in Germany, was killed in the Buchenwald concentration camp after spending 11 years in solitary confinement. There are images depicting the antifascists being captured.

The narrative of Fascists vs. Antifascists is described, and the book tells the story of the antifascists being taken away to concentration camps. Readers also learn that Ernst Thälmann, the leader of the Communist Party in Germany, was killed in the Buchenwald concentration camp after spending 11 years in solitary confinement. There are images depicting the antifascists being captured. The book describes the destruction left over by the war, mentioning how families lived in holes in the ground due to their houses being destroyed. The bottom right image shows the Soviet soldiers marching through a crowd of people raising their hats to them.

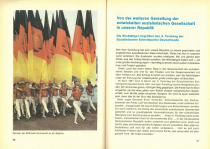

The book describes the destruction left over by the war, mentioning how families lived in holes in the ground due to their houses being destroyed. The bottom right image shows the Soviet soldiers marching through a crowd of people raising their hats to them. The further shaping of the developed socialist society in our republic. This page features a very patriotic image of athletes marching with GDR flags. The text emphasises the party’s commitment to the people, stating that they have kept their word to do anything for the happiness of the citizens of the GDR. Erich Honecker states that the GDR will flourish and that life in socialism will improve for everyone.

The further shaping of the developed socialist society in our republic. This page features a very patriotic image of athletes marching with GDR flags. The text emphasises the party’s commitment to the people, stating that they have kept their word to do anything for the happiness of the citizens of the GDR. Erich Honecker states that the GDR will flourish and that life in socialism will improve for everyone. The book describes the extensive future building projects, such as the rebuilding/modernisation of almost a million apartments and the construction of new schools, playgrounds and shopping centres. The rent for families living in these beautiful new apartments will be affordable. There is a need for more young people to become builders and more firms to produce the parts, such as windows and pipes and baths, for these homes. At the end of the text, there are comprehension questions for the students to answer.

The book describes the extensive future building projects, such as the rebuilding/modernisation of almost a million apartments and the construction of new schools, playgrounds and shopping centres. The rent for families living in these beautiful new apartments will be affordable. There is a need for more young people to become builders and more firms to produce the parts, such as windows and pipes and baths, for these homes. At the end of the text, there are comprehension questions for the students to answer.

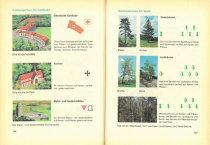

The book covers a wide range of concepts and skills, including plants and the weather, how to read from maps, or how farm animals are reared. These explanations are accompanied by clear diagrams and questions at the end of texts. At this time in East Germany, around 10% of the population worked in agriculture, which might explain why there is information particularly about farming and animals.

The book covers a wide range of concepts and skills, including plants and the weather, how to read from maps, or how farm animals are reared. These explanations are accompanied by clear diagrams and questions at the end of texts. At this time in East Germany, around 10% of the population worked in agriculture, which might explain why there is information particularly about farming and animals.

Despite a lot of fascinating books, brochures, and magazines, my favourite object was the pin of the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ)/Free German Youth (founded 1946), the only officially recognised and supported youth organisation in East Germany; it stood under the control of the GDR’s ruling party, the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED)/Socialist Unity Party. The pin shows a bright yellow sun rising into a blue sky – a symbol of hope as a ‘new day is breaking’ after war and disaster. From the beginning, the Communists in the eastern part of Germany tried to mobilise young people for their socialist project.

Despite a lot of fascinating books, brochures, and magazines, my favourite object was the pin of the Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ)/Free German Youth (founded 1946), the only officially recognised and supported youth organisation in East Germany; it stood under the control of the GDR’s ruling party, the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED)/Socialist Unity Party. The pin shows a bright yellow sun rising into a blue sky – a symbol of hope as a ‘new day is breaking’ after war and disaster. From the beginning, the Communists in the eastern part of Germany tried to mobilise young people for their socialist project.

writers, editors, translators, designers and publishers. To employ so many people to communicate in English (and other languages not represented in the Archive) shows a state willing to commit significant resources to reaching out to the world, particularly the West.

writers, editors, translators, designers and publishers. To employ so many people to communicate in English (and other languages not represented in the Archive) shows a state willing to commit significant resources to reaching out to the world, particularly the West. though, other publications contained articles written from scratch and were designed eye-catchingly with glossy paper, colour photos and coloured text. In this category, the Archive has 130 copies of GDR Review from 1978-1990. Even for the earlier issues of this magazine, the entire front cover was devoted to a colour photo and at least half the photos inside were in colour.

though, other publications contained articles written from scratch and were designed eye-catchingly with glossy paper, colour photos and coloured text. In this category, the Archive has 130 copies of GDR Review from 1978-1990. Even for the earlier issues of this magazine, the entire front cover was devoted to a colour photo and at least half the photos inside were in colour. GDR Culture. Issue 5 of this magazine, for example, reported on topics including artistic activity in Gera and the youth radio station DT 64. Travel, too, features strongly in the Archive’s holdings, reflecting the GDR’s efforts to attract tourists and their foreign currency.

GDR Culture. Issue 5 of this magazine, for example, reported on topics including artistic activity in Gera and the youth radio station DT 64. Travel, too, features strongly in the Archive’s holdings, reflecting the GDR’s efforts to attract tourists and their foreign currency. Perestroika was a political concept (1980 -1991) within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the 1980s, the economy in the USSR was crumbling, which resulted in poor living conditions, environmental problems, political disengagement, and disintegration of society. Gorbachev pursued a new approach to tackle the problems, believing that more openness in discussing problems would initiate a democratization and consequently engagement of people in much needed reforms. This included more freedom of speech and less censorship for the media and opposition groups either political or religious. These political changes were reflected in Sputnik magazine, which became a means of promoting and disseminating the new course in the Soviet Union internationally.

Perestroika was a political concept (1980 -1991) within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the 1980s, the economy in the USSR was crumbling, which resulted in poor living conditions, environmental problems, political disengagement, and disintegration of society. Gorbachev pursued a new approach to tackle the problems, believing that more openness in discussing problems would initiate a democratization and consequently engagement of people in much needed reforms. This included more freedom of speech and less censorship for the media and opposition groups either political or religious. These political changes were reflected in Sputnik magazine, which became a means of promoting and disseminating the new course in the Soviet Union internationally. The June issue from the end of the 1980s reflects the political transformation in the Soviet Union. It compiles articles critical of social, political, and economic developments and endorses non-conformity and free speech. The front cover of the issue shows a young punk, an example of openness and tolerance of individuality, in this case of a subculture. The acceptance of other groups or subcultures who did not follow ‘the socialist norm’ is here seen as a progressive step towards reform.

The June issue from the end of the 1980s reflects the political transformation in the Soviet Union. It compiles articles critical of social, political, and economic developments and endorses non-conformity and free speech. The front cover of the issue shows a young punk, an example of openness and tolerance of individuality, in this case of a subculture. The acceptance of other groups or subcultures who did not follow ‘the socialist norm’ is here seen as a progressive step towards reform.