The Salamanca declaration (UNESCO, 1994) is often thought to mark a turning point in the move towards inclusive education. It declared that education was right for all and that the education should take place in regular education settings. It has been reinforced by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (aka CRPD – UN, 2006) which asserted that “States Parties shall ensure an inclusive education system at all levels” (Article 24 of CRPD). Ten years after this, the UN took stock of the situation and showed that 87% of UN Member States had ratified the convention (weblink). Figure 1 shows the status of the convention around the world.

Figure 1 Taken from the weblink above, this map shows the legal status of the CRPD. Most of Europe is coloured orange which indicates the highest level of agreement with the CRPD and its optional protocol.

Figure 1 Taken from the weblink above, this map shows the legal status of the CRPD. Most of Europe is coloured orange which indicates the highest level of agreement with the CRPD and its optional protocol.

My interest in this topic had however been piqued earlier because a friend of mine began work for the European Agency for Special Needs Education which publishes data on the extent of inclusive education in a number of member countries through a biennial survey. When I looked at the data tables in the surveys I was struck by how different the levels of inclusive education were across the jurisdictions of Europe. I have carefully used the word “jurisdiction” here because nation states do not necessarily have unified education systems. For instance in the UK there are four education systems which are evolving differently (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales). In Germany each of the Länder have their own education policies and so on. So my first step was to look at the data. I chose as an indication of inclusive education to display fully segregated education which is the converse of inclusive education because I naïvely believed that the data would look much the same whereas the definition of inclusive education is less clear. Some forms of inclusive education simply educate the children with SEN in the same buildings as other pupils even though they have little contact with each other. Other systems use inclusive education to mean that children with SEN are educated in the same classrooms and following the same curriculum at the same time.

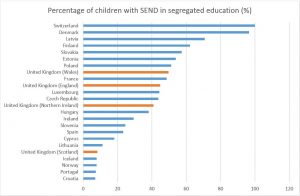

According to the latest survey data the percentage of pupils with Special Educational Needs in fully separate education settings varies between 100% in Switzerland and 7.11% in Croatia. The data is displayed in figure 2:

Figure 2 Bar Chart showing the Percentage of children with SEN educated in entirely separate settings. The home nations are shown in orange to highlight their differences. Note that some large countries (Belgium, Germany) are not represented in this dataset.

I have been trying to understand why the rates of segregated education are so high in some countries and almost non-existent in others. In the USA researchers have found that school districts with more people in them (largely urban ones) have much higher rates of segregated education than school districts with scattered populations (rural ones). There is however a confound between population density and poverty with more rural communities often having fewer financial resources than urban districts. At the level of jurisdictions as represented in figure 2 we might be able to identify whether there is higher correlation between population wealth and segregation. Alternatively it might represent a problem of geographical distance – populations that are more scattered cannot transport their children to segregated schools which might be several hours travel time away from the child’s home. So I compiled data on rurality from the EU, income levels from the trading economics website and a measure of income inequality (The GINI coefficient) from the World Bank. Unfortunately the correlations between percentage of children in segregated education bear little statistical relationship to any of these indices: Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Segregation-GDP per head) = 0.17, p = 0.88; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (segregation-GINI coefficient) = 0.03, p=0.88; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Segregation-rurality index) = -0.04.

There are a couple of other factors that might be significant but which are not obvious from the data presented so far. Using the 2008 dataset on the levels of inclusive education shows that Italy is statistically different from the other jurisdictions – see figure 3. Why might this be so?

Figure 3 shows the proportion of children with SEN educated in inclusive settings in the primary age range. The only point that is labelled is Italy which has nearly 100% of its pupils with SEN in inclusive settings. The plot is a double square root plot which compares the square root of the number of pupils with SEND at primary age in inclusive settings (vertical axis) with the square root of the number of pupils with SEN of primary age in segregated settings (horizontal axis).

Data on the trends of inclusive education in Europe are instructive. They show that Italy has always had an exceptional percentage of children with SEN in inclusive settings throughout the 21st century. This probably because legislation in Italy to promote inclusive education started in 1971 and in 1992 legislated to include all pupils in inclusive settings with the exception of a few schools for the deaf and/or blind that pre-existed the legislation.

In Germany the situation mirrors that of Europe more generally. The Ministers of Education of all the Federal Länder agreed in 2010 to promote inclusive education. There is a wide variation between the Länder in the proportion of pupils educated in specialist segregated settings. Figure 4 shows the percentages of children educated in inclusive settings.

Figure 4 The percentages of primary age children with SEN in inclusive settings grouped by Land (Province). The greatest proportion of children educated in inclusive settings is seen in Bremen, with hte least in Bayern and Hessen. The bars in colour represent those Länder studied by Blanck, Edelstein & Powell (2013).

This data distribution is strikingly similar to the data from Europe displayed in figure 2. Blanck, Edelstein and Powell (2013) argued that the differences between the Länder might be due to institutional inertia and the presence of powerful forces resisting change not due to ideology, but potentially because of their financial and human investments in segregated education. They discuss four possible mechanisms for the persistence or otherwise of segregated education:

- Functional reproduction – the existing institutions continue to exist because there is no advantage to change from providing segregated education to providing inclusive education. The segregated institutions continue to provide all the examples of education of children with SEN so other forms of education are not able to demonstrate their abilities to be effective educators.

- Power-based reproduction – existing institutions have power because they have sequestered to themselves the knowledge necessary for effective special education and therefore they do not actively promote an inclusive model, and promote a segregated one;

- Law based reproduction – the system of laws may maintain a segregated system of education for SEN. Conversely, if a jurisdiction decides to enforce inclusive education (e.g. Italy) then inclusive education will spread.

- Utilitarian reproduction – essentially a financial argument for stability of maintaining a system of segregated education since the costs of change are too high.

In the German examples chosen by Blanck et al. (2013) there were very clear differences between the Länder. In Schleswig-Holstein, the Education minister determined as early as 1988 that inclusive education would be the route for the education of children with SEN. The educational professionals also developed training to enable inclusive education, thus weakening the power based reproductive stability. The authors point out that Bayern has long held itself apart as a separate entity within the German Federation and the traditions of education have been more closely linked to religious influences than elsewhere. In particular the Roman Catholic Church had invested heavily in providing charitable activities such as specialist and segregated education for children with SEN. The control of the Ministry of Education of local officials was seen as weaker since they had little local data on which to base their decisions.

Conclusions

The two sets of data (Europe, Germany) taken together show that important disparities in the success of inclusive education may arise. The data available do not suggest that the persistence of segregated education is due to economic factors, but rather as Blanck et al. (2013) have argued there are more “sociological” reasons for the success or otherwise of inclusive education. In this context one might note that Italy was also a major player in developing radical implementations’ of community (integrated) care for all people with mental illness (e.g. Reali & Shapland, 1986) including those that found themselves in police cells. In the future, it might be instructive to investigate the extent to which the four mechanisms suggested by Blanck et al. (2013) can hinder the changes in policy, or whether as the examples of Italy and Schleswig-Holstein suggest, a strong legislative impulse is also necessary for the abolition of segregated education.

References

Blanck, J. M., Edelstein, B., & Powell, J. J. (2013). Persistente schulische Segregation oder Wandel zur inklusiven Bildung? Die Bedeutung der UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention für Reformprozesse in den deutschen Bundesländern. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Soziologie= Revue Suisse de Sociologie, 39(5), 267-292.

Reali, M., & Shapland, J. (1986). Breaking down barriers: the work of the community mental health service of Trieste in the prison and judicial settings. International journal of law and psychiatry, 8(4), 395-412

Dr Tim I. Williams, D.Phil., AFBPsS

Associate Professor, Programme Director for the PGCert SENCo, Pathway Lead for Inclusive Education

HCPC registered Clinical and Educational Psychologist

Accredited Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapist

timothy.williams@reading.ac.uk