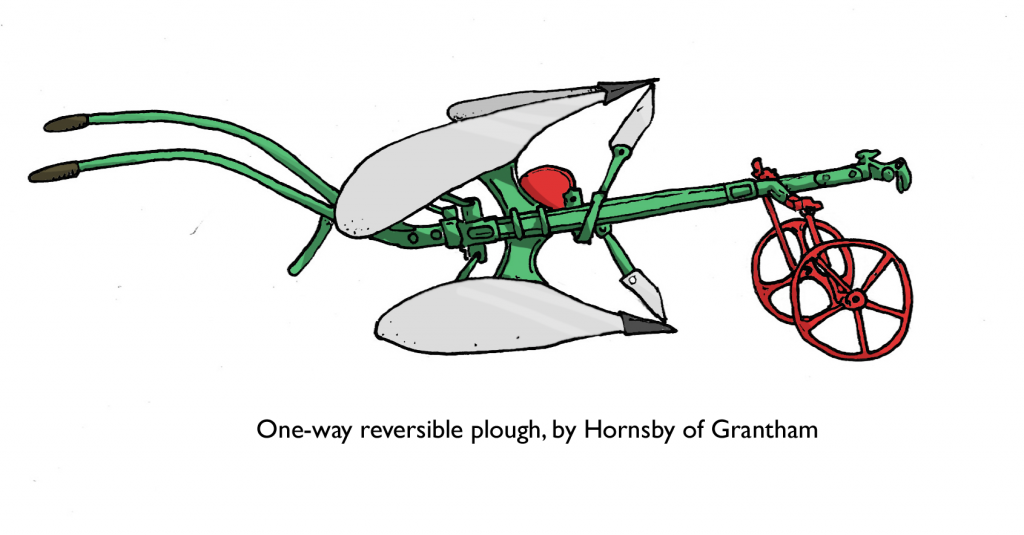

The new temporary exhibition at MERL is now open to the public. Collecting the countryside: 20th century rural cultures is largely comprised of objects drawn from the Museum’s recent Collecting Cultures project. This ran from 2008 until earlier this year and involved the Museum’s curatorial team selecting items that connected in some meaningful way with the twentieth century countryside or with perceptions of rural life. With the generous support of the Heritage Lottery Fund, many of these things were then purchased for the MERL collection. This exciting departure has enabled the Museum to address new stories previously untold at MERL, as well as to acquire many materials we’re not particularly well known for holding. So, alongside the usual mishmash of smocks, ploughs, and wagons you will now find a rich mixture if advertising materials, posters, rurally-themed toys, and much, much more! You can read more about the wider project here and follow the early stages of the collecting process by accessing the original blog.

It was always hoped that the opportunity to acquire new (or perhaps we should say ‘slightly old and largely unfamiliar’) artefacts would lead to fresh avenues in the exploration of our rural past. The book shown here is a perfect case in point. It superseded another text by the same author entitled ‘The Map That Came To Life’ (1948) and both volumes were illustrated by the graphic artist Ronald Lampitt. His striking work also adorned the pages of many Ladybird books and, although largely unrecognised for these extraordinary illustrations, he now has a small but rapidly growing following. Both of the books can be seen on display in the new exhibition. However, what the labels won’t reveal is that MERL has recently opened a dialogue with Lampitt’s grandsons. So, as with these books and very much like the English countryside itself, this exhibition should be read as far more than the sum of its parts. We hope to use the varied collections within it to find new points of departure, innovative approaches, and exciting dialogues through which to champion the people whose powerful ideas and creations have helped to shape the way we come to know and understand the English countryside.

The exhibition will serve to help the Museum explore how best to incorporate more recent histories and ideas about rurality into its displays as part of the new Our Country Lives project. As well as exploring how we interpret and use the countryside, the exhibition asks you as a visitor what you think of the issues and events of the 20th century and how the museum can best act to record and communicate them. Feel free to comment on the blog, or visit the exhibition itself to leave your own opinions!

What would you collect to represent your idea of the English countryside? What do you think the future might hold for rural life in the UK? What would you like to see in a redisplayed MERL?