Two publications from Raina MacIntyre of the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales[i] suggest that bioterrorism or accidental lab release could explain the origin of the MERS coronavirus. Is this a possibility? For me the answer is a very firm NO.

In essence the authors use standard epidemiology parameters to assess the pattern of MERS infections to date. The methodology is fine but the dataset used is not. The accepted problem for any modelling is the quality of the data used for the predictions, cynically termed the GIGO problem (garbage in, garbage out), a minor change in which can have a disproportionally big outcome. Think about the numbers that were predicted to have nvCJD (human BSE) or to die in the last influenza pandemic – both hugely overestimated early on in the epidemics. The issue with MERS is the dataset is small and much of it uncertain (the number of cases increased sharply following the change of Saudi health minister in June but these cases were mostly anecdotal as the patients are all dead. The precise details of the cases and technical proof of MERS infection are lacking). It is true that the exact origin and route to man is still unclear but there are no grounds to invoke bioterrorist or accidental release. For bioterrorism the virus clearly doesn’t work well in man so is hardly going to change the course of anything – it is a poorly transmitting virus so why would it be released? And who is it targeted at? Similarly, accidental release would require a local lab working on the virus or a very similar virus – none known, especially in the Middle East. In the latter case the epidemiology would also clearly trace back to the originating lab instead of being all over the place.

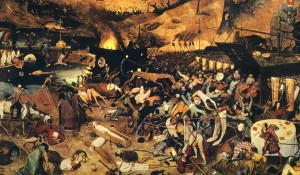

Pieter Bruegel’s “The Triumph of Death” is a favourite accompanying picture for bioterrorism texts. But is it a realistic scenario for the Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus?

The latest molecular studies show that the virus is able to infect camel, goat, cow, and sheep cells, which would fit the idea of a zoonotic origin (probably bats) that gets across to domestic livestock, likely as a silent infection that is not reported. Occasionally and via circuitous routes it gets to man where it can lead to severe respiratory distress, especially if the patient is already compromised in some way. The age and male predominance of cases to date fits with typical social roles that would interface with livestock. My own view is that low level contamination of food is also a possibility and the recent finding that the virus can survive for several days in unpasteurised milk shows this is a realistic possibility. Overall however the data are too fragmentary to offer a clear answer.

The papers from UNSW do not offer any direct evidence for a deliberate or accidental release of MERS-CoV. With our present state of knowledge you might as well drag up viruses from outer space (nonsense that was wrongly invoked to explain the SARS outbreak). It is none of these things. MERS CoV is a newly recognised and rare zoonotic infection whose pattern of spread will only become clear when more case controlled studies like those recently initiated by the new Saudi health minister have been completed. Science will get to the bottom of MERS, not speculation.

- MacIntyre CR. The discrepant epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Environment Systems and Decisions. Formerly The Environmentalist. 2014 10.1007/s10669-014-9506-5

- Gardner LM, MacIntyre CR. Unanswered questions about the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). BMC Res Notes. 2014 Jun 11;7:358. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-358.