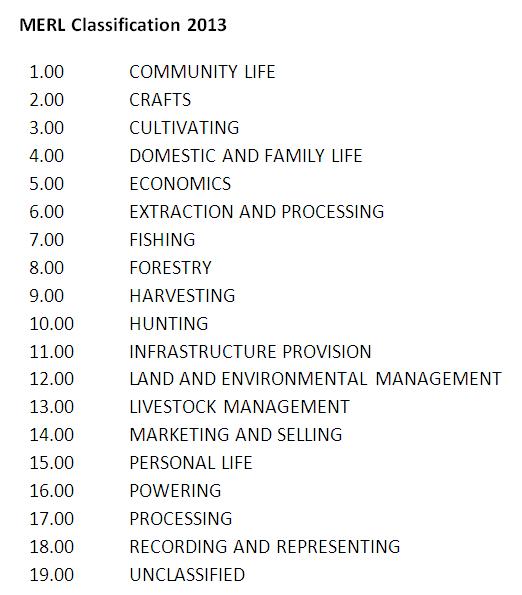

For those of you who have been following my posts (here, here and here) on revising the MERL Classification, you’ll be pleased to hear that yesterday afternoon I finally finished the hard work on it!!! It’s now ready for a final round of consultation before I begin building it properly in Lexaurus, our vocabulary software. I’ve circulated the revised Classification to the Rural Museums Network mailing list, but if you’re not on the list and would like to see it, please send me an email.

As well as putting together the final Classification, and providing scope notes to help define the primary and secondary headings, I have also mapped each of the primary and secondary headings in the existing version to the new version, so that the changes can be implemented easily when everything has been finalised.

Having been immersed in the Classification for so long, it’s quite hard to take a step back so consultation will be really useful in ensuring that everything is clear and makes sense. For example, is it obvious what the primary and secondary headings mean and what falls under them? Are the scope notes clear and accurate, or do we need to add to the definitions and examples? Does the mapping between the existing and the new versions work? Are there any further mappings to be made between the MERL Classification and SHIC (Social History and Industrial Classification).

Despite being rather wary of the Classification at first, I’ve really enjoyed this process and I am really looking forward to seeing it when it’s done. And it will be great to hear what the rest of the rural museums sector thinks – from both those who use the MERL Classification (either in its current or previous form), and those who don’t.