(Text of a paper given by Billy Smart at ‘Walking in Eternity’, University of Hertfordshire, 3 September 2013)

(Text of a paper given by Billy Smart at ‘Walking in Eternity’, University of Hertfordshire, 3 September 2013)

What I’m going to do today is examine the spatial realisation of a fantastical world in the 1981 Doctor Who story, Warriors’ Gate, draw some conclusions as to how the story’s distinctive visual style is inextricable from its narrative form and consider how the drama shows and investigates fantasy itself.

I’m going to do this in relation to the strong affinities between Warriors’ Gate and Jean Cocteau’s two films Orphee (1950) (a reimagining of the myth of Orpheus, the poet who travels to the underworld in order to rescue his wife Euridice from death) and – especially – La Belle et la Bête (1946), his telling of the beauty and the beast story. Commentary on Warriors’ Gate tends to mention the similarities of mise-en-scene and visual motifs between the films and the programme, but only ever in passing. What I want to do today is consider how these forties cinematic antecedents work in greater depth, and what they mean for the viewers’ understanding of the eighties television story.

It’s my contention that the use of Cocteau motifs is ingrained in the narrative of Warriors’ Gate, and acts as something more significant towards our understanding of the story than a handful of convenient borrowed visual devices. Instead, the references are integral to the visual and philosophical construction of the world of Warriors’ Gate. Cocteau’s conception of film has been described as “cinematic poetry”. David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson provide a useful definition of this poetic effect, describing Cocteau’s films as:

[S]elf-consciously “poetic” works, seeking to create a marvelous world sealed off from ordinary reality and to convey imaginative truths through evocative symbols. (…) Cocteau conceived rich images that could be translated into many media, confirming his belief that the poet is not merely a writer but rather someone who creates magic through imaginative means. (2003: 380-1)

Cocteau himself, a polymath who – as poet, novelist, dramatist, director, designer and artist – created both written and visual art, accepted this poetic conception of his films, finding and layering the rhymes that exist between diffuse images in his cinema, just as he did with words in his verse:

[F]or me the image-making machine has been a means of saying things in visual terms instead of saying them with ink on paper. (1954)

Creating a whole work from this approach required a “syntax”, obtained as much through the clash between images as the connection between them. Through adopting this discordant syntax (which lacked the sense of flow that appealed to movie critics) films could become ‘vehicles for thought’:

My primary concern in a film is to prevent the images from flowing, to oppose them to each other, to anchor them and join them without destroying their relief. (1954)

‘Warrior’s Gate’, an exceptionally complex Doctor Who story with a narrative that is difficult to make linear sense of, operates through just such an unsettling syntax. Set in the negative space of E-space, as opposed to the positive universe of N-Space, the story concerns a slave ship, marooned in E-Space by time winds. The ship’s slaves, the Tharils, are a race of lion-people used as navigators by the slavers because of their extrasensory psychic powers.

The Tharils lead the crews of the slave ship and TARDIS to a world behind a magical mirror, revealing that the lion-men were once the masters of their own kingdom, when they in turn enslaved humans.

It is also the story in which the Doctor’s companion and fellow time lord, Romana, parts company with him, to live amongst the Tharils, taking K-9 with her.

Set in a non-world of white empty voids, obviously artificial monochrome gardens, cobwebbed castles and magic portals, Warriors’ Gate is understood by the viewer through imagistic metaphor and associative logic, rather than through concrete and linear narrative.

The story is structured through “overt poetry, where thematic associations link the very fabric of the world together as much as through scientific reason” (Sandifer, 2012).

This non-linear storytelling has sometimes attracted hostility – a typical review reading:

[‘Warriors’ Gate’] is told in such a complex way that it fails totally to be comprehensible to anyone without a lot of time for the programme and access to a video recording. And there are more of them than there are of us. It may be a brilliant experimental television drama, but is unforgivable in its contempt for the family audience. (…) there’s so much to fathom out that even the Doctor is baffled until the very end. (Owen, 1997: 21-2)

Two early eighties TV innovations helped 1981 viewer understanding of the story, particularly amongst younger viewers – the home video recorder, which allowed stories to be immediately re-watched – ideal for finding sense in an allusive narrative – and the rapid growth of promotional music video, most famously David Bowie’s ‘Ashes to Ashes’ (1980, d. David Bowie and David Mallet), bringing abstract videographic landscapes to everyday television, their visual ontology similar to that of Warriors’ Gate.

The unconventional form of Warriors’ Gate can be in part attributed to the novice status of its production crew. It was 25 year-old Steven Gallagher’s first television script, having previously written science fiction for radio plays and his first novel. Gallagher’s initial script has been described by Script Editor Christopher Bidmead as being “a novel” rather than a work for TV, very long and primarily consisting of passages of description (Arnopp, 2009: 45-6). His aim was to write a strongly horror-based serial, since he disliked the “softer”, comical, approach to Doctor Who of recent years. He approached the task with the assumption that he was writing for three different audience constituencies: action and monsters for the children, mystery and imagination for the teenagers, and intellectual drama for the adults (Wiggins, 2009).

Director Paul Joyce had previously only directed one television drama, a Play for Today for BBC Birmingham, and his inexperience of directing drama in the TV studio affected both the process of making Warriors’ Gate as well as the style and form of the programme. Joyce hoped to make the serial in a distinctively filmic style, setting up pre-production screenings of several films that he wanted to emulate, including Kiss Me Deadly, Dark Star and Cocteau’s Orphee and Testament d’Orphee. He used the TV Centre studio like a film studio, his working method being to shoot scenes twice and then edit them together in postproduction. This caused great delays and was unpopular with BBC Staff, with Joyce at one stage being sacked from the production, until it became apparent that no one else could comprehend his camera script and he was quickly reinstated. Production was also delayed by a walkout of staff when Joyce insisted on filming the studio lights “off the set”, a safety officer declaring a set unsafe and a strike by BBC carpenters. The drama required extensive work in postproduction (Pixley, 2002, Wiggins, 2009).

Because of this preoccupation with film style, it had been assumed that the use of Coctovian motifs was a directorial decision on the part of Joyce, but Steve Gallagher has emphatically refuted this notion, to the extent of sending copies of his original draft script to writers who suggest this in print (Gallagher, 1994). Bearing this explicit authorial intent in mind, I suggest that the frequent use of Cocteau references in Warriors’ Gate acts as considerably more than as an act of homage, but as a visual code for understanding the story world of the drama. Gallagher uses the visual world of Cocteau as a template for achieving two essential concerns of Doctor Who –

Firstly, to form impossible connections between parallel worlds and realities. This is a recurring feature in Doctor Who, not just the transitional space of the TARDIS itself, but parallel spaces within worlds themselves, that can often be formulated as representing dream or unconscious states for those who cross between them – for example, the virtual reality domain of the matrix (‘The Deadly Assassin’, 1976) or the Continual Event Transmuter machine that stores sections of planets on a series of slides (‘Nightmare of Eden’, 1979). To cross from one world to another requires either a process (e.g. being connected to a machine) or a physical portal (such as crossing into a screen).

Gallagher took the idea from Orphee that mirrors are gateways into the other world.

The Princess and other emissaries of Death travel through mirrors –

– as do the Tharils in Warriors’ Gate.

The creation of trick effects for the mirror was much more complicated in Cocteau’s film studio, requiring false sets with elaborate carpentry. In contrast, BBC Television Centre Doctor Who production used an identical effect for all journeys through the mirror.

Joyce wanted to recreate Cocteau’s most celebrated rippling effect for passing through the mirror, but the use of mercury was vetoed as being too impractical and dangerous.

The mirror in Orphee is frequently shown to act as much as a barrier as a gateway.

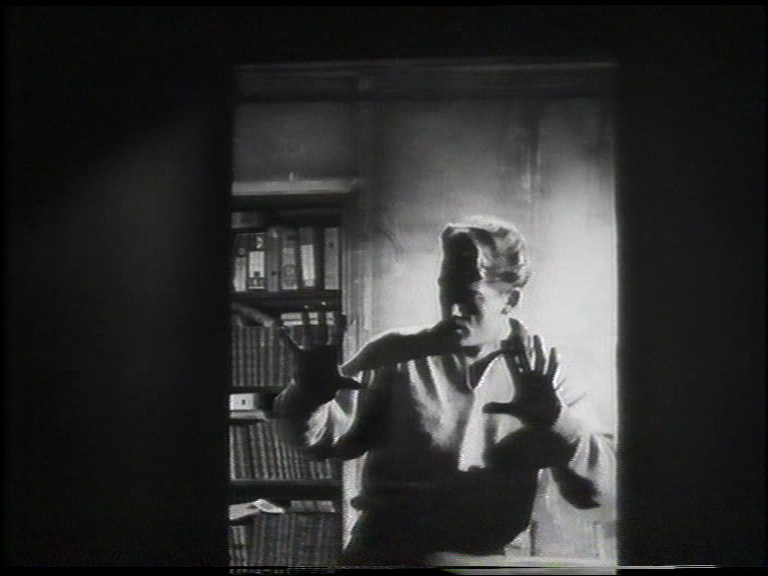

Orphée is eventually enabled to travel through the mirrors in part by putting on gloves (much as the Doctor’s hand becomes changed by the time winds); and in part by blocking out the concerns of our world, much as lead Tharil Biroc urges the Doctor and Romana to “Do nothing” to escape the slave ship. Ability to traverse the mirror in Warriors’ Gate is shown to be a process only allowed to those with telepathic sympathy; Tharils can pass through mirrors like doors, Time Lords and Ladies can learn the gift, but the frustrated slavers lack the wherewithal to pass through, as seen here as the Doctor looks through from the other side of the mirror.

The mirror is not the only means of communication with the underworld that Warriors’ Gate shares with Orphee. Cryptic messages from the realm of death are transmitted by radio in the film –

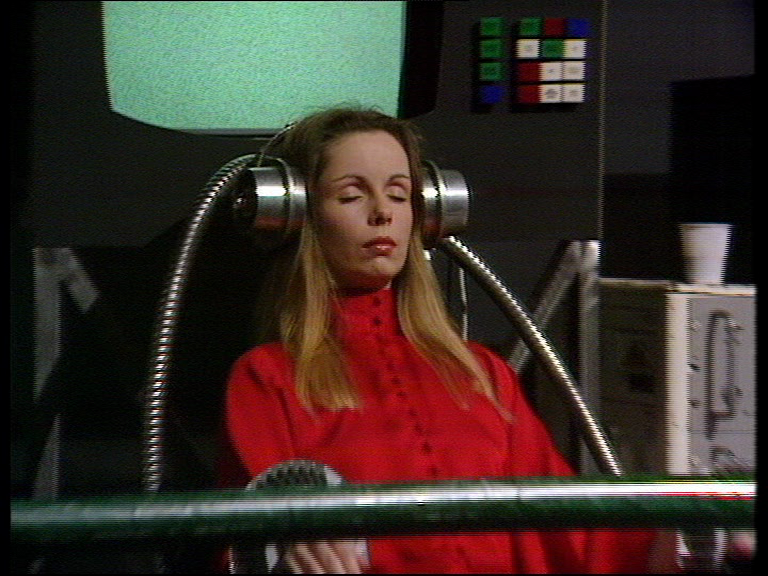

– a device used in two settings in Warriors’ Gate. First the time-sensitive Tharils, and then Romana are wired up in the hope that they will receive messages from beyond the gateway, the headphone apparatus drawn from Orphee.

And, like Orphee, the Doctor tinkers with cumbersome equipment to receive haltering, stentorian, instructions from the other side through the airwaves.

The second lesson that Gallagher takes from Cocteau in order to create a strong Doctor Who story is the application of the topography of La Belle et la Bête to create an imaginative fantastical world, governed by its own rules and logic. From my own experience, the abiding memory of watching Doctor Who as a child was the powerful, immersive, sense of looking in on a fully realised fantastical world, with access limited to just a fleeting 25 minutes on Saturday afternoons in the autumn and winter. Popular memory tends to concentrate upon the fear felt by the infant viewer of Doctor Who, but there was also an equally strong aspect of fascination to childhood engagement with the programme.

The various landscapes that Warriors’ Gate adopts from Belle et la Bête feel like a more fully-realised world than a collection of stages. The Doctor’s initial arrival at the castle acts as both a quotation from – and a discourse with – the moment in the film when Belle’s father arrives in the mansion of the beast. The BBC scene repeats the same apparatus and composition used by Cocteau –

– with the Doctor also responding to the room – with its candelabra, seemingly deserted table, and empty chair – from the same position, evoking a similar mood of exploration and unease.

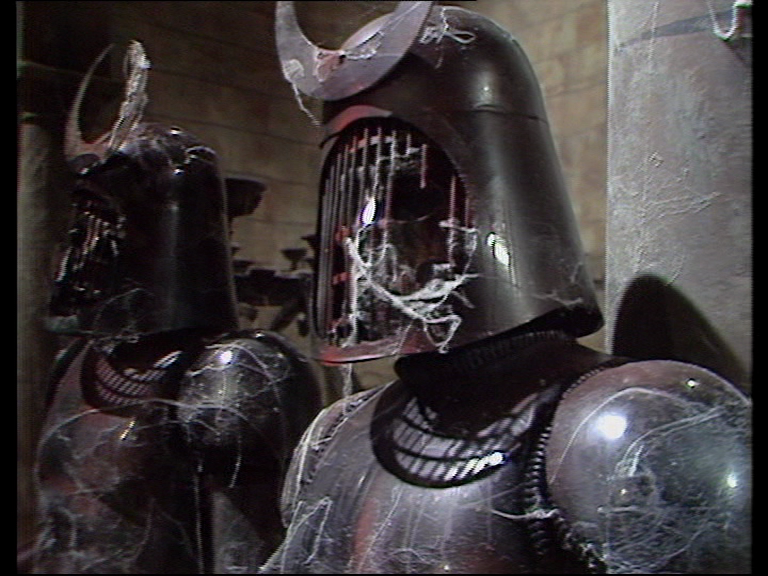

The beast’s castle is not, however, deserted, but populated by living statues!

Similarly long-dormant, but still living, suits of armour populate the Tharil castle, Gallagher deriving child-pleasing monsters (the Gundun Warriors) and suspense from Cocteau’s imagery.

In both scenes, the protagonist’s response to their alarming new surroundings is given an action through the prop of a goblet. In the film, the father takes a drink from a disembodied hand, considers, and then drinks from it.

While the Doctor arights an upended goblet, an object that the (very attentive) viewer will eventually learn that he himself upset centuries before.

While the castle room is a finely-realised interior set, ‘Warrior’s Gate’, like la Bête, presents the viewer with an impressive sense of the expansive topography of the beast’s magnificent home –

– surrounded by magical gardens

– an effect achieved by using detailed still photographs taken in the grounds of Powis Castle.

The monochrome photography elevates the onscreen garden from a potentially flat green screen special effect into an otherworldly magical location

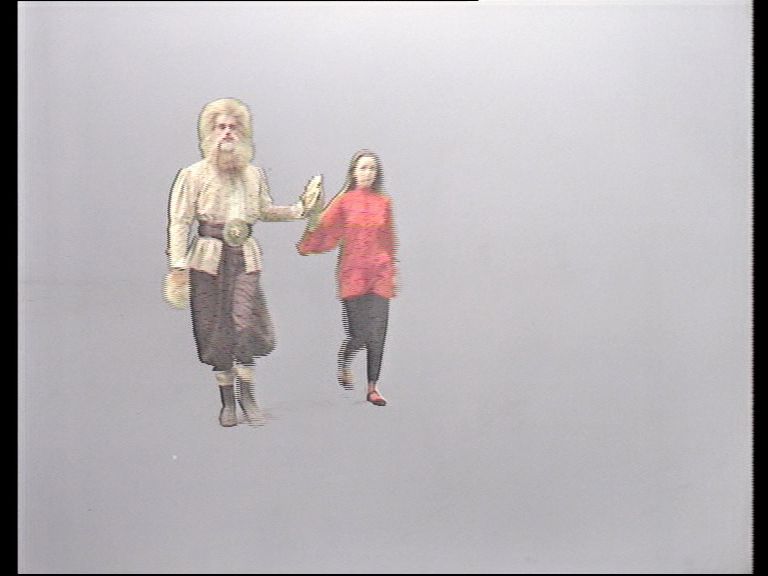

– where visitors lose their individual agency and can only follow the beast through warrens and mazes.

The monochrome artificial effect is also used for the corridors of the Tharil kingdom, reconstituting Cocteau’s grand corridors –

– and allowing characters the space to move between foreground and background in magnificent rooms

Sometimes Warriors’ Gate replicates the shot sequence of particular scenes from la Bête, the point of view shot through which the prone Belle first sees the beast –

– is also experienced by Romana and the viewer

– as, in turn, is the beast’s point of view

Perhaps the most significant visual quotation ‘Warrior’s Gate’ takes from la Bête is the hand-in-paw conjoining between Belle and the beast –

– being an action recreated by Time Lady and Tharil, signifying a point of tactile connection between two worlds of the story.

It is when presented with this touching image of union between Noble Princess and Beast, that the fantastical fairy tale source of Warriors’ Gate is most apparent, but wholly consistent with the depiction of the Tharil kingdom throughout the story. Gallagher’s imaginative use of Cocteau’s imagery – and Joyce’s application of it – are consistent with Cocteau’s own rationale for telling fantastical stories on film, which calls for great precision and craft:

[It is up to me] to avoid those impossibilities which are even more of a jolt in the midst of the improbable than in the midst of reality. For fantasy has its own laws which are like those of perspective. You may not bring what is distant into the foreground, or render fuzzily what is near. (1949)

Cocteau’s introductory prologue to La Belle et la Bete can serve as well as a justification of the form and style ‘Warriors’ Gate’:

The characters of this film obey the rule of fairy stories. Nothing surprises them in a world to which matters are admitted as normal of which the most insignificant would upset the mechanics of our world. (1946)

As much as any Doctor Who story, Warriors’ Gate works through paradoxes and confusions within and between space and time. As in Cocteau’s films, the unconventional visual aesthetic of the story means that it achieves this through poetic means. “Typically when we use the word “poetic” we really mean “lyrical,” that is, essentially working according to a non-narrative structure. Lyric poetry, contrasted with the narrative form of epic poetry, is a poetry based on the expression of emotions” (Sandifer, 2012). This lyrical storytelling acts as a boon to Warriors’ Gate, a story made during a particularly cerebral period of the show when, under the script editorship of Bidmead, it was reluctant to dramatize the emotional journeys of characters.

Because Warriors’ Gate was not conceived as a standalone viewing experience, but as four 25-minute episodes of an on-going series watched on Saturday afternoons. As a segment of a continuing viewing experience, the story would always be best remembered for the departure of Romana. It is through the appropriation of Cocteau’s world that Romana’s story works on an associative level. As in La Belle et la Bête, a lion man takes a princess into his world. For all of the sophistication and elegance of the piece its most elemental narrative fascination is achieved through fairy tale. Although the verbal storytelling of Warriors’ Gate is opaque, the essential story is told through visual means.

The celebrated words of the Princess to Orphee apply just as well to the viewer of Warriors’ Gate: “The point is not to understand, but to believe.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnopp, Jason, ‘Science Friction’, Doctor Who Magazine 407, 29 April 2009, pp. 42-7.

Bordwell, David & Thompson, Kristin: Film History: An Introduction (Second Edition): New York, McGraw Hill, 2003.

Cocteau, Jean, Beauty and the Beast: Diary of a Film: New York, Dover Publications Inc, [1949] 1986.

Cocteau, Jean, Cocteau and the Film: London, D.Dobson, 1954.

Gallagher, Steve, ‘Scripting ‘Warriors’ Gate’ – so what actually happened?’, In-Vision 54, November 1994.

Owen, David, ‘Doctor Who: The E-Space Trilogy’, Doctor Who Magazine 257, 22 October 1997, pp. 21-2.

Pixley, Andrew, ‘Archive: Warriors’ Gate’, Doctor Who Magazine 315, 3rd April 2002.

Sandifer, Philip, ‘Going To Be Alone Again (Warrior’s Gate)’: http://www.philipsandifer.com/2012/02/going-to-be-alone-again-warriors-gate.html , 2012.

Wiggins, Martin, ‘Production Information’, Doctor Who: Warriors’ Gate: BBC DVD, 2009.

Pingback: Doctor Who: Warriors’ Gate (1981) | Tombolo

Pingback: (TIMES AND) SPACES OF TELEVISION – DOCTOR WHO: WARRIORS’ GATE (1981) | British Television Drama