Our ‘Dramatic Spaces: The Imaginative World of the TV Studio’ film season continues at BFI Southbank this afternoon, with a screening of ‘The Life of Galileo’, a version of Brecht’s epic history, recorded in Television Centre for the BBC’s Festival series in 1964. Over the course of the season we will be writing short posts about each play shown, and would welcome thoughts and responses from those who attend the screenings.

Charles Jarrott’s[i] Galileo exuded a confident sense of certainty about what could and could not be achieved in the BBC Television Centre studio, acknowledging that the production was studio-made through the inclusion of cameras and the production gallery in shot, an artistic decision that complicates the view of ‘as live’ studio television as being best suited for an “intimate” form of drama.

British television of the late 1950s and early 1960s offered both bardic and dramatic forms of narrative for the viewer, bardic storytelling lying mainly in the realm of news and reporting, while television drama (especially the majority made in the studio, rather than on film) progressed in a sequential, ‘dramatic’, manner. The format of television news presented verbal information directly to the viewer through the newsreader’s narration, followed by filmed footage of the events, with an explanatory commentary on voice-over, sometimes followed by a correspondent explaining the significance of events in the studio. This structure allowed the viewer to understand news as occurring backwards and forwards in time, encouraging contemplative and dispassionate consideration through showing events in a temporal context of cause and possible effect rather than exclusively as dramatic occurrences in the present. The growth of television satire during this period also included bardic elements of narrative, such as Cy Grant’s regular ‘topical calypso’ on Tonight (BBC Television, 1957-65) and the use of sketch and monologue in That Was The Week That Was (BBC Television, 1962-3). Viewer response to Jarrott’s production of Galileo was as much conditioned by the conventions of television current affairs coverage as it was by television drama.

Charles Jarrott’s production of Galileo fulfiled Brecht’s wish for broadcasting that affected the listener (or viewer) through presenting both imaginative insights into the life and scientific investigation of Galileo and a wider, more educative, insight into the running of institutions, culminating with the directorial imposition of footage of nuclear missiles at the end of the play. The production achieved this effect by adopting its form as much from factual and informative forms of television as from exclusively dramatic ones, unlike the one previous Brecht production on BBC Television, Rudolph Cartier’s Mother Courage (World Theatre, 1959), which is always clearly a television play.

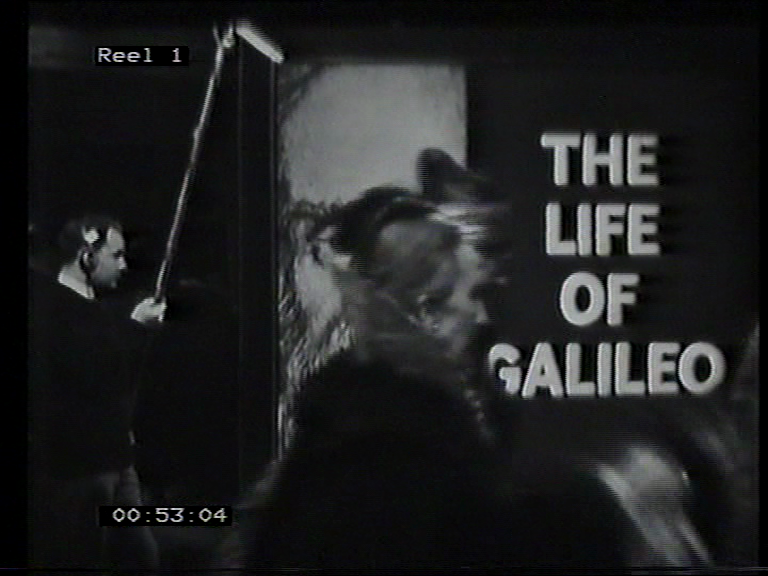

Jarrott’s production is unique among BBC television adaptations of Brecht in not disguising that it is a television programme. This is achieved through bookending the production with ‘documentary’ scenes set in the television studio. The adaptation starts by showing the studio gallery at work, with the opening music shown to be a disc being dubbed over the pictures. The studio floor is then shown to be an artificial place. It is displayed to its full extent; cameras are seen beyond the end of the flats of the scene, microphones above them, and the company milling about waiting for their cues, in costume but clearly not in character. The title placard does not fill the entire screen, but is framed by a boom operator. This presentation of the mechanics of production, in the form of cameras and microphones, makes Galileo a self-reflexive production, made manifest through its self-awareness as a work of art, and therefore a modernist production.

Although this behind the scenes display is not continued into the actual scenes of the play, it still serves an important function in encouraging the viewer to accept Brechtian dramaturgy and illusion, establishing that the following story will work as a representation, rather than an attempt to imitate the reality of Galileo’s life. The convention of showing the mechanics of studio production surrounding performance had recent precedents in British television, with the satirical series That Was The Week That Was having presented the full extent of the studio with its cameras, microphones, and audience in its live transmissions, providing the domestic viewer with a greater sense of liveness and immediacy. In particular, this introductory sequence helps to establish the convention of the narrator breaking through the fourth wall. Direct address to camera was an established convention in most forms of television in 1964, but rare and potentially disconcerting in drama. By establishing Galileo as a work of television, through showing the mechanics of the studio, Jarrott turned the figure of the narrator into a convention that the viewer might find acceptable, allowing the technique to be understood in terms of broadcasting, rather than as a theatrical tradition.[ii]

An example of how the narrator served to mediate between the dramatic scene and the television camera occurs in the transition between Scenes Two and Three. The second scene of Galileo and the Doge is set in the public space of the harbour of Venice in front of a crowd. The final shot of this scene is shown on a television monitor, watched by the narrator, who then turns to the viewer to explain how this meeting affects the story of Galileo. This use of the monitor interprets Galileo’s audience with the Doge as reportage, presented to the viewer as a news item, which the narrator then elucidates to the viewer. Allowing the narrator to view events through a monitor encourages the audience to identify with him as an everyman figure, as he has witnessed events in exactly the same way that the domestic viewer has. The narrator also is integrated into the action by the use of disguises and costumes, adopting the role of a plausible bystander for every scene, by putting on a false moustache in scene four and wearing ecclesiastical robes in scenes with the cardinals. This integration into the worlds of each scene gives credence to the authority of the narrator as a witness to the events which he explains to the viewer, while also adding a sense of theatrical artifice and a comic register of role-playing to his instruction, making him both a part of, and detached from, the events depicted.[iii]

A sense of the studio as being a space of representation, rather than replication, is followed through in the design of the production, where sets combine naturalistic and obviously artificial features. This convention is established in Scene One, where the placard that gives the title and date of the play then becomes a unit of the wall of Galileo’s home. Throughout the production this motif is continued, with banners forming components of otherwise naturalistic sets. These properties add a sense of the artifice of the performance, as well as serving an instructive purpose in illustrating the wider social world and conditions that affect each individual scene, for example blown up line drawings and woodcuts represent the buildings of the Vatican. This design, which only comprised a fraction of the set in each scene, did not appear jarring to viewers, as the completely artificial landscapes of Mother Courage had in 1959. [iv]

The production ends with a further interpolation of the world of television on to the world of Galileo, with footage of a rocket and a series of stills of great scientists since Galileo’s time. The disruptive effect of this is different to that of the studio sequence at the beginning of the play. Where the purpose of the first scene appears to be largely aesthetic, establishing the conventions of the drama that will follow, showing the viewer that the play will not be a naturalistic attempt to replicate reality, the imposition of the rocket footage seems much more ideological in intent, forcing the viewer to draw parallels between Galileo and nuclear armament. This is perhaps the closest that this production gets to “Brechtian television” or agitational drama, through presenting the viewer with striking and unheralded juxtaposition. It is significant that this moment occurs after the seventeenth century story of the play had finished, and therefore appears as a coda rather than integrated into the main body of the play, where it would appear more disruptive. This ending of Galileo appears to have been the least popular aspect of Jarrott’s production with some viewers, the BBC’s audience reporting that:

‘The parallel need not have been drawn so obviously at the end’ ‘The play provided a complete set of judgements on morality and expediency without [the need for] added effects’ (BBC WAC VR/64/243)

However, only a small minority of viewers reported these complaints, with some others considering “that these devices added to the impact of the play and heightened its scientific theme” (BBC WAC VR/64/243).

The Life of Galileo was one of the most successful and well-received stage adaptations of the 1960s, and was chosen as one of the first BBC1 productions to be repeated on BBC2. Audience research for the production reveals a high level of enthusiasm, the reaction index of 78% far above the 58% recorded for Mother Courage five years earlier (BBC WAC VR/64/243). What is striking about the enthusiasm expressed towards Galileo in this audience research is the combination of intellectual stimulation and emotional engagement that viewers reported. Great approval was expressed towards the most naturalist elements of the production; historical detail and production values were felt to accentuate the story and the acting:

‘Costume plays with a factual background can generally be relied upon to provide good entertainment’ wrote an Architectural Assistant, and this example, it seemed, had been extremely successful in giving ‘reality and life to history’ (…) a production which drew the warmest praise on all counts – settings, costumes, make-up, camera-work – all were ‘quite marvellous’, it seemed, lavishly and imaginatively recreating the very essence of the period, and carrying the action along with such smooth dexterity that attention was firmly riveted from first to last. (BBC WAC VR/64/243)[v]

The factor that raised the viewers’ approval in acclaiming this production as exceptional was found in Brecht’s dramaturgy, presenting Galileo with a sequence of dramatic dilemmas, and clearly placing them within a wider historical context. Through presenting these dilemmas within the television studio, mediated to the viewer through the contemporary figure of narrator-as-broadcaster, Charles Jarrott’s production gave the pay a particular, medium-specific, sense of immediacy and relevance. Viewers report having found the story of Galileo exceptionally gripping and significant, praising the production for its instructional qualities, and recommending its educational value:

‘It was like being transported back in time, and understanding all the difficulties of Galileo’s struggle against ignorance and power’ (…) The theme too, it was held, had all the elements of a good play – ‘the human struggle, the historical and scientific interest, the religious question and the present-day parallel’ (…) ‘it is such a pleasure to see a play with a real message and meaning’ (BBC WAC VR/64/243)

Viewers reported a great sense of sympathy and affection towards Galileo, as well as admiration for Leo McKern’s performance, perhaps making him a more empathetic figure than the “untragic hero” of the epic drama suggested by Walter Benjamin:

Galileo was “presented as ‘a humorous, living, breathing, loving, enjoying human being’, who ‘became a real person, not just a name in a science text book’ (…) ‘The irony, the shades of meaning, the subtleties of character, the humanity of the man – so many facets to relish. It was delightful’ (BBC WAC VR/64/243)

The Life of Galileo works as a fully realised Brechtian production, that not only used the conventions of studio camera movement and vision mixing to explain and illustrate the decisions made by characters and their place within a wider social structure, but also succeeded in placing these characters within a sustained bardic narrative. This bardic storytelling operated through the use of the guiding figure of the narrator, as well as through the integrated use of captions, monitors, sets that were clearly artificial and, in the sequence of nuclear missiles, the use of interpolated non-original footage. The production achieved an original Brechtian form that was unique to television, through not disguising the programme’s means of production: a television studio, with microphones and cameras.

The undisguised artifice of Jarrott’s production assisted viewers’ ability to follow the story of Galileo and to draw conclusions from it. Encouraged by the confidence that they were being told a story, viewers felt permitted to empathise with the figure of Galileo, whilst being able to place his life within the context of the state of Rome in the seventeenth century. Jarrott’s adaptation managed to achieve this effect by following a model that derived as much from forms of television other than drama, such as news and commentary, an innovation distinct from the more abstract and less broadly social experimental studio tradition established by the Langham Group. This created a model for studio television that encouraged a drama that was ‘dramatic’ in Brechtian terms as opposed to the more realist model that ‘as live’ drama generally used. This rethinking of the studio and how it could be used for television narrative showed unexpected possibilities for taped ‘as live’ drama, capable of engaging and encouraging the curiosity of a broad television audience.

[i] Charles Jarrott (1927-2011), after starting his career as an actor, became one of the most respected and prolific directors of contemporary drama in British television in the 1960s, directing 34 separate Armchair Theatre (ABC/ Thames, 1956-74) productions between 1959 and 1969, as well as some controversial single plays for the BBC such as The Wednesday Play: Cock, Hen and Courting Pit (1966) and Harold Pinter’s Tea Party (1965) and The Basement (1968). Jarrott moved to Hollywood in 1969, winning a Golden Globe for his first film, Anne of the Thousand Days (1969).

[ii]Audience research appears to suggest that the use of a narrator was merely accepted, rather than embraced by Galileo’s otherwise enthusiastic audience (“I like a play to proceed without somebody telling you the story every few minutes”, BBC WAC VR/64/243), although the convention of narrator does appear to have been understood by the audience, rather than seen as confusing.

[iii] This narrative convention had also been recently used in the theatre in the role of ‘The Common Man’ in Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, a highly successful and popular play.

[iv] See the BBC Audience Research Report for Mother Courage (BBC WAC VR/59/372)

[v] Such few adverse comments as can be found attack the play on the same terms, treating it as representative of television period costume drama per se: “I am completely at a loss why these plays are produced. I hope the actors got a kick out of it, dressing up like a lot of B.Fs. I endured it for an hour until I could cheerfully had shot the lot” (BBC WAC VR/64/243)

Pingback: Exercise Bowler by T. Atkinson (BBC, 1946) | SCREEN PLAYS

Pingback: From Television World Theatre to the BBC Shakespeare: The fluctuating status of the classic play on BBC Television 1957-1985 | Forgotten Television Drama

I saw this remarkable adaption in 1964 and

it shaped my view of both Galileo and Brecht.

The use of Verfremdungstechnik made the

action very immediate to me. McKern was palpably

engaged in a drama played at a high level of

both intellectual and emotional commitment.

When he later went on to fame as Rumpole, I

kept thinking of how much more he might have done.

His radio portrayal of Scatcherd in Trollope’s

“Dr Thorne” came close to recapturing the visceral

integrity of his depiction of Galileo Galilei.

David Broadhurst