The final play in our season, ‘Dramatic Spaces: The Imaginative World of the Television Studio’ is Desert of Lies, written by Howard Brenton for television. The play interweaves the narratives of two expeditions to the Kalahari, one historical and one contemporary.In 1848 a family of Christian missionaries travel to the desert to find and civilize a mythical  tribe of savages whose heads are in their stomachs. Over a century later, in 1984 an explorer, George (Tim Wylton), leads a journalist, Sue (Cherie Lunghi) and a young man, Jake (Mick Ford), recently unemployed and up for the adventure, in an attempt to follow in the missionaries footsteps, to find out what happened and seek out the tribe. Neither group is able to cope with the harsh reality of the desert conditions: The missionaries are driven mad by the heat and solitude, and slowly perish through hunger and, in the case of Uncle Abel (Tom Bell in a stunning performance),

tribe of savages whose heads are in their stomachs. Over a century later, in 1984 an explorer, George (Tim Wylton), leads a journalist, Sue (Cherie Lunghi) and a young man, Jake (Mick Ford), recently unemployed and up for the adventure, in an attempt to follow in the missionaries footsteps, to find out what happened and seek out the tribe. Neither group is able to cope with the harsh reality of the desert conditions: The missionaries are driven mad by the heat and solitude, and slowly perish through hunger and, in the case of Uncle Abel (Tom Bell in a stunning performance), alcoholism. In the modern group, George is fatally wounded after their jeep overturns, Jake eventually dies of thirst, and Sue, the sole survivor, is rescued by bushmen and bears a child by one of them, eventually returning to England but refusing to tell her story. Brenton cleverly weaves in moments of great humour through two bushmen who observe the struggling group with amusement, cleverly inverting Western voyeurism and paternalistic attitudes while introducing a welcome relief from the scenes of suffering: (“Who are these idiots?”/ “We could leave them food.”/”No, they won’t know what it is.”)

alcoholism. In the modern group, George is fatally wounded after their jeep overturns, Jake eventually dies of thirst, and Sue, the sole survivor, is rescued by bushmen and bears a child by one of them, eventually returning to England but refusing to tell her story. Brenton cleverly weaves in moments of great humour through two bushmen who observe the struggling group with amusement, cleverly inverting Western voyeurism and paternalistic attitudes while introducing a welcome relief from the scenes of suffering: (“Who are these idiots?”/ “We could leave them food.”/”No, they won’t know what it is.”)

In his excellent account of the play, Richard Boon (1991: 304) outlines how the play’s concern with the ‘colonial past and how that is perpetuated in modern thinking’ is developed:

In his excellent account of the play, Richard Boon (1991: 304) outlines how the play’s concern with the ‘colonial past and how that is perpetuated in modern thinking’ is developed:

‘Both groups go to Africa seeking to impose on it their own, mythologized views of what it ought to be. For the missionaries, it is a matter of finding the savages in order to make them repent and wear clothes and to discover a new ‘promised land’. George dreams that the ‘”headless tribe’ may be a reality, a ‘transformed human race” which possesses the secret of life. Sue is “hungry for experience: it’s a vice”… [contacting] an exiled SWAPO leader [guerillas against South Africa], for advice’ who, ‘though tolerant and polite […] satirizes her as a “decent, concerned white” who can never grasp the truth of Africa, the reality of its poverty, the horrors of its tyrannies and of its wars of liberation.’

The interest in characters’ visionary aspirations is shared with Brenton’s prior television play, The Paradise Run, in which the experiences of two disaffected soldiers are told in parallel, each pursuing different notions of paradise.

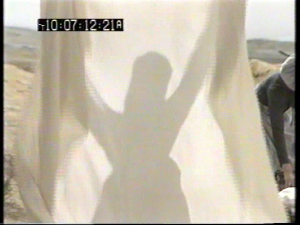

Piers Haggard’s strikingly accomplished direction emphasises the play’s dream-like qualities, his ethereal desert imagery both evoking the characters’ delirium in the desert heat and suggesting transcendent, utopian visions. He frequently layers images through slow mixes, integrating the parallel stories while creating surreal and beautiful montages within the frame, combining these with other beautifully composed, haunting images (below).

Piers Haggard’s strikingly accomplished direction emphasises the play’s dream-like qualities, his ethereal desert imagery both evoking the characters’ delirium in the desert heat and suggesting transcendent, utopian visions. He frequently layers images through slow mixes, integrating the parallel stories while creating surreal and beautiful montages within the frame, combining these with other beautifully composed, haunting images (below).

The Kalahari landscape is a triumph, painted backdrops depicting the endless desert expanse, with perfect lighting and a hazy heat effect (achieved perhaps using filters or gauzes?) achieving an authenticity beyond what I would have imagined possible in the studio.

The Kalahari landscape is a triumph, painted backdrops depicting the endless desert expanse, with perfect lighting and a hazy heat effect (achieved perhaps using filters or gauzes?) achieving an authenticity beyond what I would have imagined possible in the studio.

The landscape’s effectiveness is also maximized through Haggard’s framing strategies. Many scenes are framed with an  object or figure very close in the foreground, keeping the background out of focus, and the camera is often kept at ground level (a visual device used by Haggard in other productions such as The Blood on Satan’s Claw) creating a sense of space, as well as generating surreally oblique angles, suitable for the play’s subject-matter. Haggard and the production designer, Stuart Walker, recall having used an early form of digital image compositing, via a Soho production house, to achieve a couple of the very long shots of the desert contained in the play, but otherwise the production was confined to Studio 1 of Television Centre.

object or figure very close in the foreground, keeping the background out of focus, and the camera is often kept at ground level (a visual device used by Haggard in other productions such as The Blood on Satan’s Claw) creating a sense of space, as well as generating surreally oblique angles, suitable for the play’s subject-matter. Haggard and the production designer, Stuart Walker, recall having used an early form of digital image compositing, via a Soho production house, to achieve a couple of the very long shots of the desert contained in the play, but otherwise the production was confined to Studio 1 of Television Centre.

The scheduling of Desert of Lies (at 9:35pm on Tuesday 13th March, 1984) meant that much of the production’s audience was lost to the lavish period drama serial, The Jewel in the Crown, showing on ITV until 10.00pm, and indeed the BBC Audience Research Report for the play (ARR/TV/84/52) states that many viewers tuned in late because of this, but were unable to ‘pick up the thread’. The appearance of the play’s setting was also criticised by some, who thought it ‘so false that it spoilt the total effect by creating a feeling of unreality’, suggesting that it suffered by being put up against the sumptuous and expansive location- filmed Indian landscapes on the other side.

Many viewers in the BBC’s sample were also confused by the production’s unconventional, non-linear time frame which cuts between the parallel expedition stories and contains flashbacks showing how the modern characters came to be there, finding it ‘too mixed-up and disorientating’. Conforming to a common, recurring pattern in BBC audience responses to single plays, many of the objections voiced by respondents concerned it’s unreality – some viewers finding it ‘far-fetched’ and the characters ‘highly implausible and unbelievable’. However, a small group ‘thoroughly enjoyed’ it and ‘praised its originality […] [saying] it was ‘unusual and different’’ and ‘thought-provoking’.

Bibliography

Boon, Richard, 1991, Brenton The Playwright, London: Methuen Drama.

Poole, Michael, 1984, ‘Lie Detector’, The Listener, vol. 111, no. 2848, 8 March 1984, p. 30.

May I ask where you found a copy of this? I would love to watch it too!

The best way to view commercially unavailable BBC programmes (that survive) is to request a viewing at the BFI – http://www.bfi.org.uk/archive-collections/searching-access-collections/research-viewing-services

I was in this, and I too would love to view a copy.