Written by Sharon Maxwell, Archivist (Cataloguing & Projects)

I have recently been cataloguing the personal papers of Professor Francis J Cole, (1872-1959), the first Professor of Zoology at the University of Reading. The fascinating papers in the Cole collection include research for his academic writings and publications, bibliographies and indexes relating to his library and his bibliographic studies and photographic material including thousands of glass negatives and lantern slides used by Cole in his teaching. Cataloguing this material has given me an insight into Cole’s research methods and his interests.

Cole was born in London, England on 3 February 1872. On leaving school Cole’s aim was to go to Oxford and read zoology. He learnt zoology at the Royal College of Science, and he also attended lectures at the Royal Institution and studied at Christ Church, Oxford and the University of Edinburgh. In 1894 he was appointed lecturer in zoology at Liverpool University College, later the University of Liverpool. He stayed there for twelve years and combined work during term time at Liverpool with research during vacation at Jesus College, Oxford. In this way he obtained a B.Sc.

In later years Cole re-used many of his old College notebooks to record his research notes, examples of which can be seen here, alongside a photograph of Professor Cole taken in 1939 (MS 5315/2/2)degree at Oxford by research in 1905.

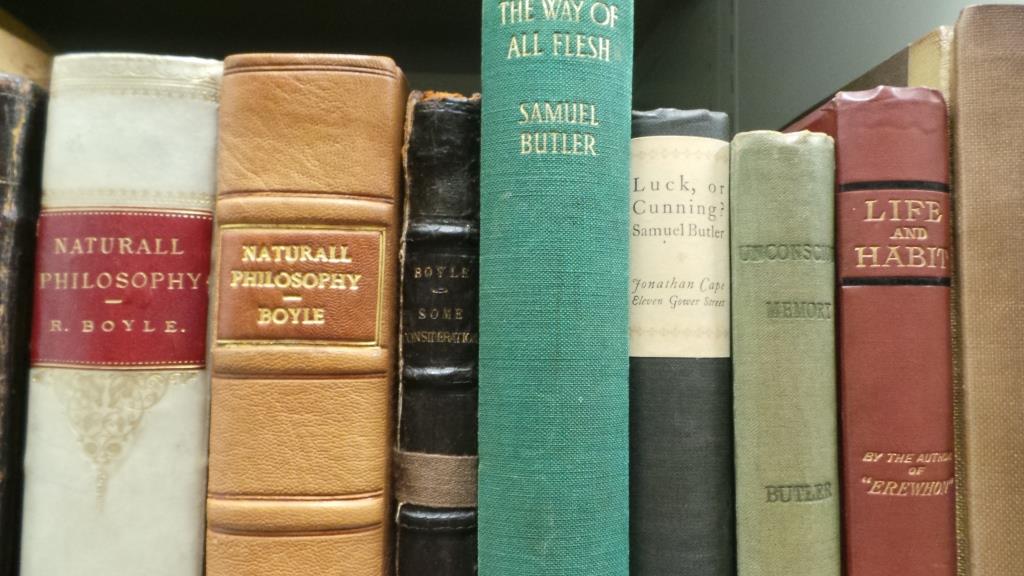

degree at Oxford by research in 1905. In 1906 Cole took up an appointment as lecturer in zoology at University College, Reading, and in the following year became the first occupant of the chair of zoology, which he held until his retirement in 1939. In these thirty-two years he built up a flourishing department, founded a Museum of Comparative Anatomy which is now called by his name, and collected a magnificent library of early works on medicine and comparative anatomy.

He was awarded the Rolleston Prize at Oxford in 1902 for his researches on the cranial nerves of fishes, Chimaera. Later he published a series of papers on the myxinoid fishes and received the Neill Gold Medal and Prize of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1908. His D. Sc., Oxford, followed in 1910. During World War I he was commissioned in the 4th Territorial Battalion

A small image of Professor Cole in his uniform and a notebook he used to record notes for his work with his Battalion on the east coast during WWI, you can see his diagram detailing positions and trenches

of the Essex Regiment and was stationed on the east coast in charge of a coastal gun emplacement.

Returning to Reading after the war Cole turned more and more to the history of biology. His collection includes research for many of his major publications on this subject, including the zoological researches of Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), and his history of comparative anatomy.

The material that has survived in Cole’s archive gives you an insight into his style of research, he liked to produce detailed indexes to sources that he used, which refer you to material within his own library and to sources he found in other libraries and museums, so that you can closely follow his research path. He also took great care with the illustrations produced to accompany his published writings, drawing many of the original images himself and annotating proofs until they were perfect for publication.

Proofs and original drawings by Cole for his study on the nerves and sense organs of fishes, (MS 5315/1/2)

Cole clearly liked to enliven his lectures and talks, and his collection includes thousands of glass

negatives and lantern slides. Ceri, our Reading Room Assistant is currently cataloguing these images and each negative will soon be digitised so that an image of the negative will appear alongside its catalogue description. Our volunteers Ron and Jan are carefully re-packaging these items into acid-free covers and boxes to preserve them for the future.

Professor Cole’s papers are available for research in the reading room, reference MS 5315 and the glass negatives will be available to view on our online catalogue in the near future.

Sources and further reading:

Much of the biographical information above was taken from an article written by N.B. Eales in the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1959, Vol. XIV, No. 1

See also the Cole Library and the Cole Museum for further insight into Professor Cole’s collections