An earlier post dealing with the period from 1905 to 1926 showed that a South Cloister had been planned from earliest days of the London Road Campus. A further post covering 1926 to 1947 showed how these plans changed over time and were never carried out. The purchase of Whiteknights in 1947 put paid to further developments.

In the meantime Sharon Maxwell, Special Collections Archivist, has found three items that fill some of the gaps and provide more clarity:

-

- Notes dated 1907 by the Architects, W. Ravenscroft and C. S. Smith, on the New Hall and Buildings (Ref.: UHC Box 1466).

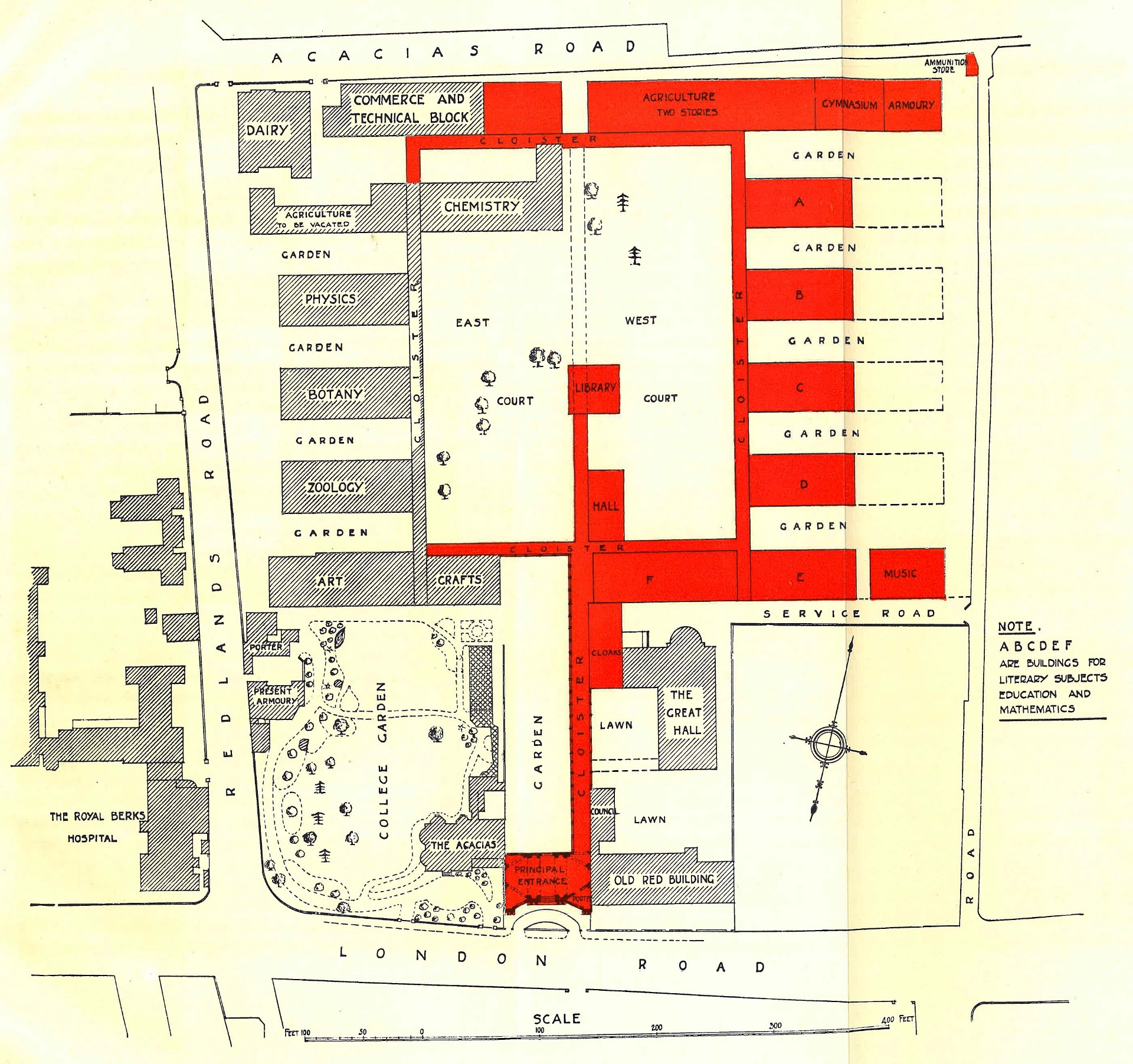

- A Report on New Buildings, submitted to the Council of the University by the Vice-Chancellor in January 1928 (Ref.: UHC CM GOV 8).

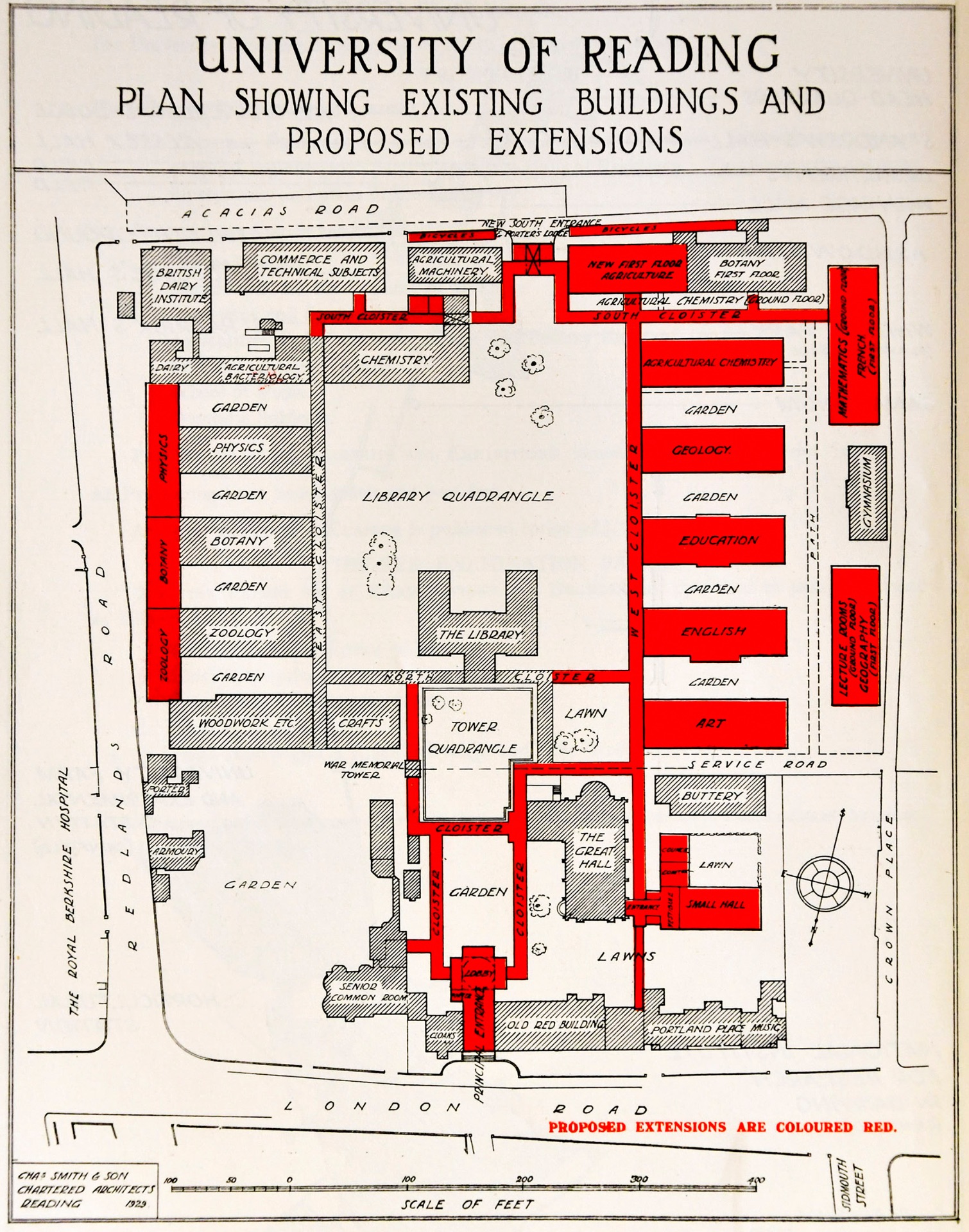

- A full-sized original plan of the site that includes proposals for a new South Entrance, a South Cloister and the West Cloister, dated 1929 (Ref.: UHC – PLANS Box 1).

The site plan of 1929

The plan shows how the route of a proposed South Cloister is linked to the creation of a new South Entrance on Acacias Road. It is similar to other plans of 1926 and 1929 except that its large size allows additional detail. One interesting feature that weren’t on the other maps is the inclusion of a ‘creeping way for pipes’ running from the East Cloister to the West Cloister and eventually turning south to link with the Agricultural Chemistry and Botany Building (now L22).

The Architects’ Notes dated 1907

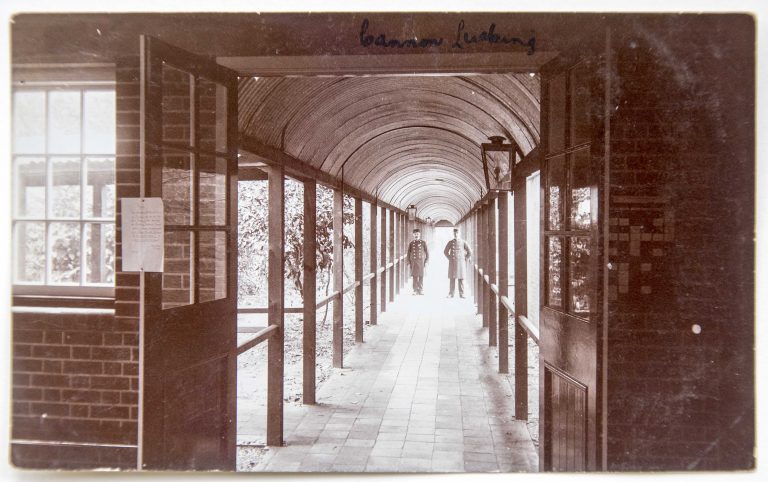

This wasn’t the only mention of a ‘creeping way’, however ; the Architects’ Notes of 1907 found by Sharon Maxwell mentions them in the context of both the Great Hall and the East Cloister:

‘A creeping way has been formed under the whole length of the Cloister, in which all pipes, both hot water, gas, and cold water supply are laid. Here are also all the electric cables, for supplying both these one-storey buildings and the new Hall. Thus periodical inspection is made a simple matter, and any future extensions or improvements are facilitated.’ (p. 6).

The Vice-Chancellor’s Report on New Buildings, 1928

The relevance of the proposed new creeping way is that its course had also been considered (and rejected!) as a possible route for the South Cloister. This is made clear from the third document located by Sharon Maxwell: the Vice-Chancellor’s 1928 report to Council.

This report makes the case for a new ‘southern entrance gateway’ complete with porters’ lodge (possibly residential) on the grounds that, with halls of residence and homes of staff mainly to the south of the site, Acacia Road had become the main means of access. The gateway would be linked to the South Cloister, as shown in the above plans.

As can be seen, however, one problem was that the cloister would have needed to cut through the spur of the Chemistry Building (now L19).

Nevertheless, it was concluded that no other route was feasible, the route following the course of the proposed creeping way having been ruled out:

‘It was suggested formerly that the link from Long Cloister to long cloister might pass immediately to the north of Chemistry (East). This route, however, would mean (1) obstruction to the lighting of these chemical laboratories, (2) a serious diminution of the Library Quadrangle, and (3) the destruction of one, probably more than one, of the trees which form a beautiful group to the north-west of Chemistry (East). These trees are a yew, a walnut, a cedar, and a lime. Their preservation from age to age should be a matter of duty to all who care for the amenities of the University.’ (Vice-Chancellor’s 1928 report to Council, p. 14).

The position of the four trees can be seen clearly in the enlarged area of the 1929 plan (see above). The image below shows the same area today but I don’t know whether any of the trees are the same.

The South Cloister and the new entrance never came to pass. Fortunately, neither did a suggestion in the same report to improve the North Entrance on London Road by demolishing Green Bank and the School of Music.

Thanks

Many thanks to Sharon Maxwell and the Reading Room team for all their help.