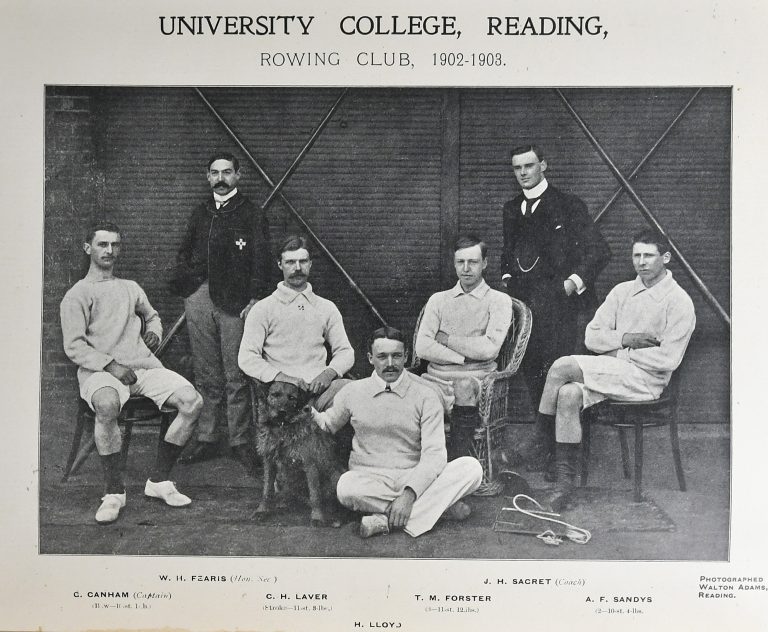

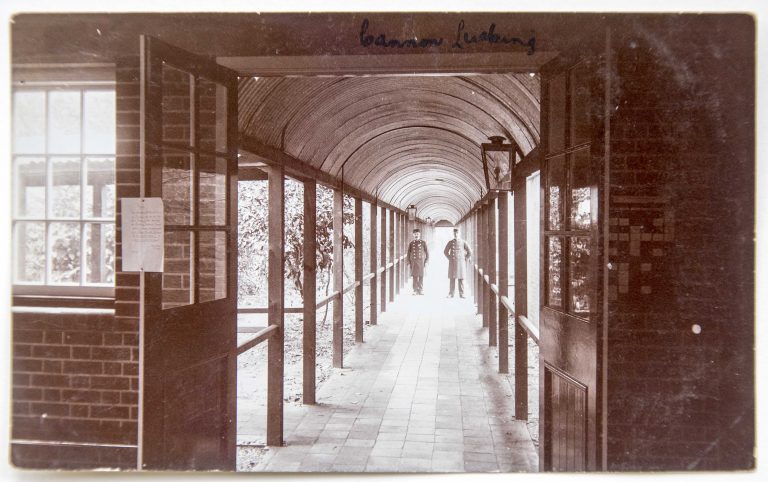

During the early days of the London Road Campus, a wide range of picture postcards was produced showing scenes of the College grounds and buildings. Many of these have been preserved in the University’s Special Collections and they include views of the cloisters, the front entrance, porters’ lodge and Green Bank. There are also interior shots of student hostels and halls.

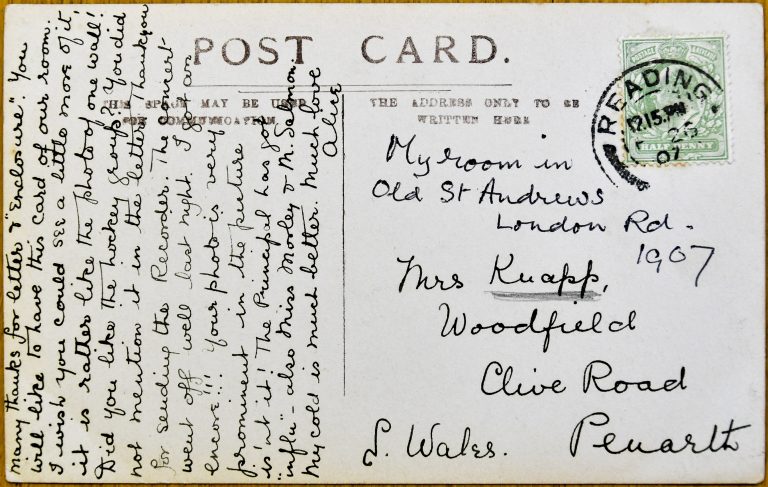

Very occasionally a card turns up that has been written on, sent home and, at some stage in its long history, has been returned to the University and retained in its archives.

One such example is this card posted in 1907 that shows the sender’s room in St Andrew’s Hostel.

The reverse of the card reveals that it was sent by someone called Alice to a Mrs Knapp in Penarth near Cardiff.

The written message reads as follows:

‘Many thanks for letter & “Enclosure”. You will like to have this card of our room. I wish you could see a little more of it, it is rather like the photo on the wall! Did you like the hockey group? You did not mention it in the letter. Thank you for sending the Recorder. The concert went off well last night. I got an encore!!! Your photo is very prominent in the picture is’nt [sic] it! The Principal has got “influ” – also Miss Morley & M. Salmon. My cold is much better. Much love Alice.’

The three members of academic staff with ‘influ’ were:

- The Principal: W. M. Childs who became Reading’s first Vice-Chancellor in 1926;

- Miss Morley: Edith Morley who became Professor of English Language in 1908, the first woman to hold an equivalent position in the UK;

- M. Salmon: Professor Amédée V. Salmon, Professor of French.

So who was Alice? It seemed logical to assume that she was writing to her mother or close family member and I was convinced that I had seen the name Alice Knapp somewhere in the College records.

Lists of graduates were published in the college calendars so it was a simple matter to discover that Alice graduated in 1907 with a second class honours BA in English and French (hence the references to Edith Morley and Amédée Salmon).

The following year she was made an Associate of University College Reading (with Distinction) by virtue of her honours degree.

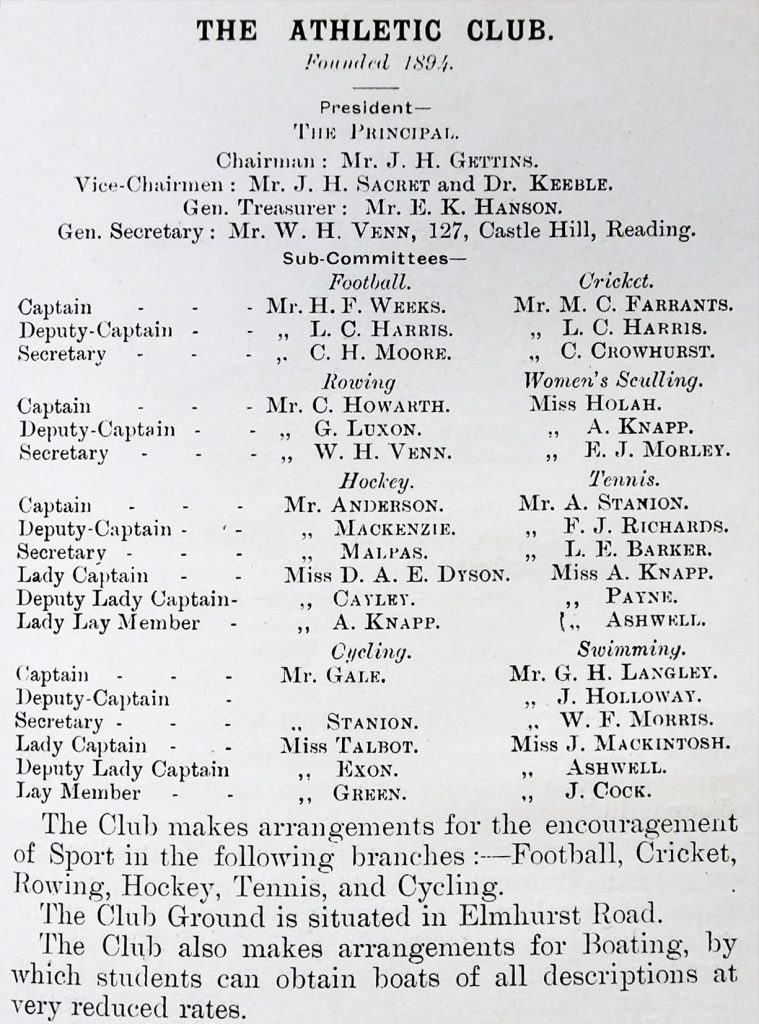

Lists of committee members of College societies in the Calendars show that Alice was a student who enjoyed extra-curricular life to the full.

- In 1906-7 she was:

- Deputy-Captain of Women’s Sculling,

- Lady Lay Member of the Hockey Club,

- Lady Captain of Tennis,

- Member of the Debating Society Executive Committe Calendar.

- In 1907-8:

- Vice-President of The Women Students’ Union (founded in 1906),

- President of the Women’s Branch of the Students’ Christian Union.

- And in 1908-9:

- Secretary of the Debating Society.

I wondered why she was still on committees after the award in her degree. The answer is in the lists of Education students – she was training to be a teacher, and in 1908 she passed the one-year postgraduate ‘Certificate (Theoretical and Practical) of the Teachers Training Syndicate, Cambridge‘.

ST ANDREWS HOSTEL

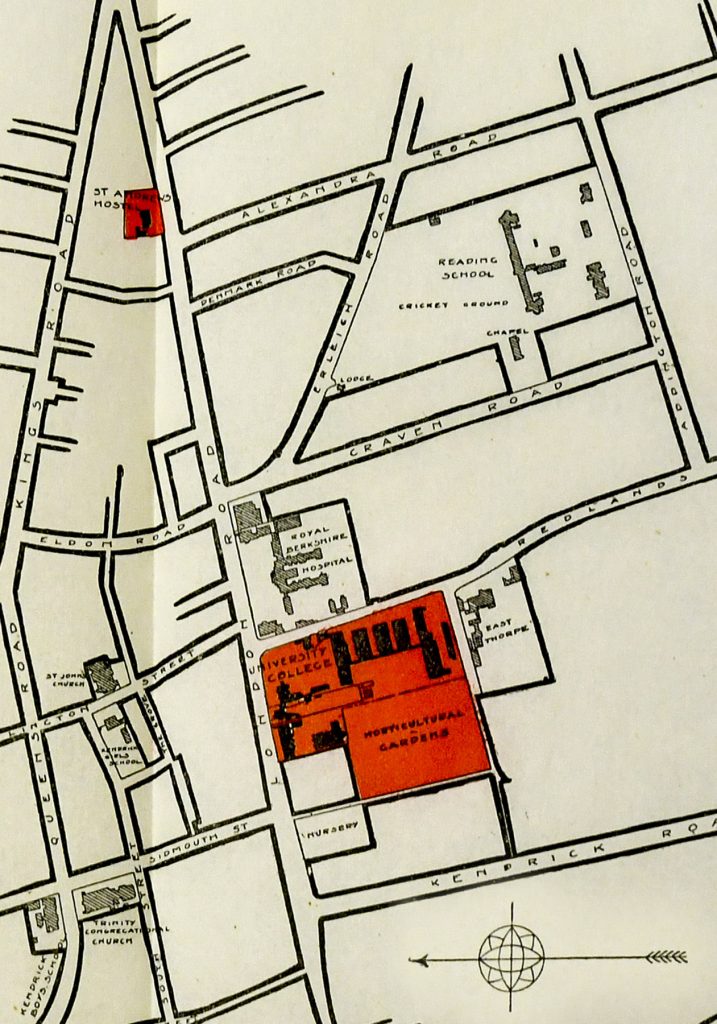

With regard to Alice’s accommodation, note that the words ‘My room in Old St Andrews London Rd. 1907‘ above the addressee indicate that Alice was lodging in the original hostel in London Rd rather than St Andrew’s Hall on Redlands Rd (see map below). The site for the latter was offered to the College by Alfred Palmer in 1909 and formally opened in 1911 (see Childs’s memoir, p. 176). Originally called ‘East Thorpe‘, it is now occupied by the Museum of English Rural Life and the University’s Special Collections.

The hostel in London Road was run by Mary Bolam, Censor of Women Students, as shown by the Student Handbook of 1908-9.

POST SCRIPT

I don’t know what happened to Alice Knapp when she left Reading. All I can find is an announcement of her BA in The Englishwoman’s Review (see front cover below) in an inside section headed University and Educational Intelligence. The Review apparently recorded the academic qualification of every woman graduate.

THANKS

To Professor Viv Edwards for locating the census records of the Knapp family in Penarth.

SOURCES

Childs, W. M. (1933). Making a university: an account of the university movement at Reading. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

The Englishwoman’s Review of Social and Industrial Questions, Vol. XXXIX, No. 1, January 1908.

University College Reading. Students’ handbook. Second issue: 1908-9.

University of Reading. Calendar, Issues from 1906-7 to 1910-11.

University of Reading Special Collections, MS5305: University History, Photographs – Halls, Great Hall.