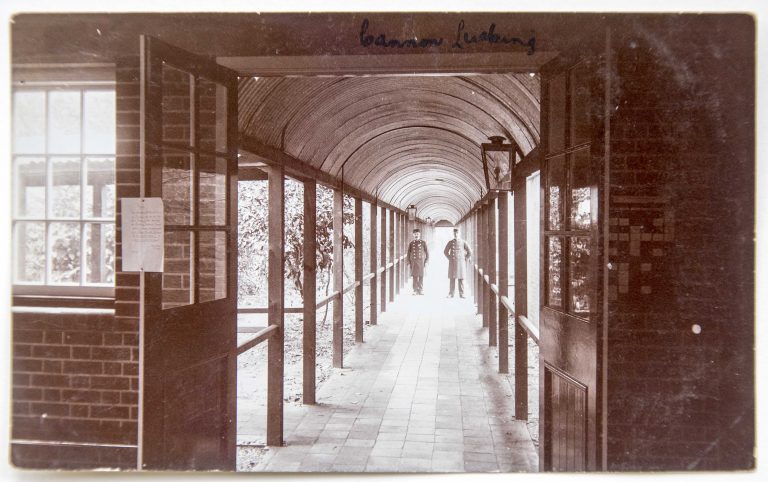

Of the many postcards produced by University College, Reading, the image below is not the most inspiring view of the London Road campus.

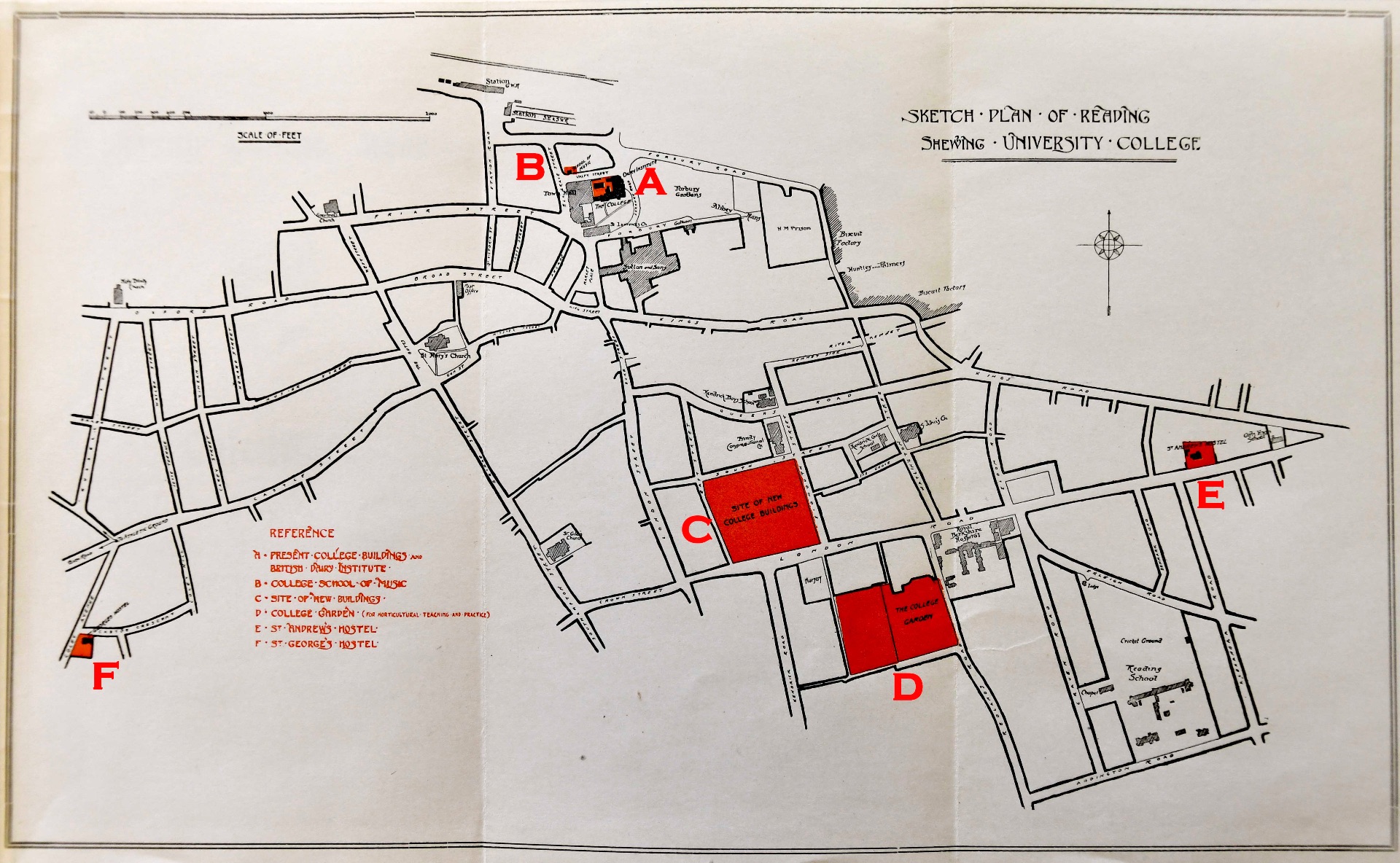

It shows the east cloister looking north towards Acacias and the porters’ lodge. In the distance, behind the Botany Department, is the sign for Zoology and Machine Drawing and, behind that, the sign for Building Construction. This matches a site plan published in the Students’ Handbook in 1907; the original Physics building would have been just behind the photographer.

There are much better images of the cloisters from this period, but what makes this postcard particularly interesting is that the student who sent it to her mother in Gosport was the young Nellie Eales who went on to work for the College and University for 42 years (retired in 1954), and lived to reach her hundredth birthday in 1989.

The message reads as follows:

‘Thanks for the chemistry apron. It will do very nicely. We shall have to get a new Strasburger [see note below] as it must be up to date. It will come to about 13/6 I expect.’

She continues:

‘Imagine having to run along 3 cloisters the length of this one when you are late. The Chemistry, Physics and Geography Halls are beyond this. The view looks towards the older part of the college. Where the posts occur on the R. hand side are gardens. There are beautiful flowers about still. We had a splendid time on Sat at the at Home. Please keep this p.c. as I want to get a collection of Reading College views.’

Written upside down in the space at the top it says: ‘Love from Nellie.’; and in very faint writing: ‘What about galoshes? It is wet here.’

Nellie Eales combined her studies in Science with Teacher Training. She passed the two-year course for Primary Education students (Class I) in July 1909 and was awarded her BSc (Hons, Pass Division II) in 1910.

Following graduation, she worked briefly for the Marine Biological Association before being appointed Curator of the Zoological Museum at University College, Reading In 1912. The museum had been founded by Professor Francis Cole in 1906. Today the Cole Museum is located in the new Health and Life Sciences Building on the Whiteknights Campus and still contains the skeleton of the circus elephant that figures prominently in the image below.

By the beginning of the academic year 1912-13, the museum’s collection had already been completely catalogued and labelled, and Eales’s duties are described in the College Review of December 1912:

‘The Curator will be employed in the first instance principally in making anatomical preparations to assist students in their routine work, and when this is accomplished she will enter upon the much larger task of making preparations illustrative of the general principles of comparative anatomy.’ (p.21)

During Professor Cole’s frequent absences on military duty between 1914 and 1919, Eales took over the Zoology Department laboratory and covered his teaching. She became Lecturer in Zoology officially in 1919, and in 1921 was the first woman at Reading to be awarded a PhD. This was followed by a DSc in 1926.

Dr Eales had a highly successful academic career, details of which can be found in Claire Clough’s post on the Special Collections Blog: “Guardian Angel” of the Cole Library: Dr Nellie B. Eales. The post also recounts how, following the death of Professor Cole, she arranged the transfer of his vast collection of rare volumes (The Cole Library) to the University and compiled the printed catalogue. She is also celebrated for donating a valuable Book of Hours from the early 1400s.

One thing that surprises me, given her academic standing within and beyond the University, not to mention her indispensable contribution to running the Zoology Department, is that it took until 1951, only three years before her retirement, for her to be promoted to senior lecturer.

Nellie Eales died in 1989 shortly after her 100th birthday. Her obituary was published in the Journal of Molluscan Studies.

An online exhibition about the Cole Collections, curated by Claire Clough, can be found here.

Note

‘Strasburger’ refers to the Botany textbook by Professor Eduard Adolf Strasburger, originally published as ‘Lehrbuch der Botanik für Hochschulen’ in 1894. An English translation of 1898 was purchased by the University College library under the title ‘Text Book of Botany’ in 1903.

The wording of the postcard is ‘a new Strasburger’, which sounds as though the students had been urged to buy an updated edition. The German original had reached its 8th edition by the time Eales had sent her card, so it is likely that the English translation followed suit.

Sources

University College, Reading. Official Gazette. No. 30. Vol. II, 3rd December, 1903.

University College, Reading, Annual Report and Accounts, 1908-09, 1909-10.

University College, Reading. Calendar, 1910-11.

University of Reading. Proceedings of the University, 1953-4.