On learning that Edith Morley had become Professor of English Language in 1908 (see my previous post) one might have thought that it was the end of the story. Far from it – and this time she didn’t just threaten to leave, she actually submitted a formal letter of resignation!

1911-12: A risky attempt at renegotiation

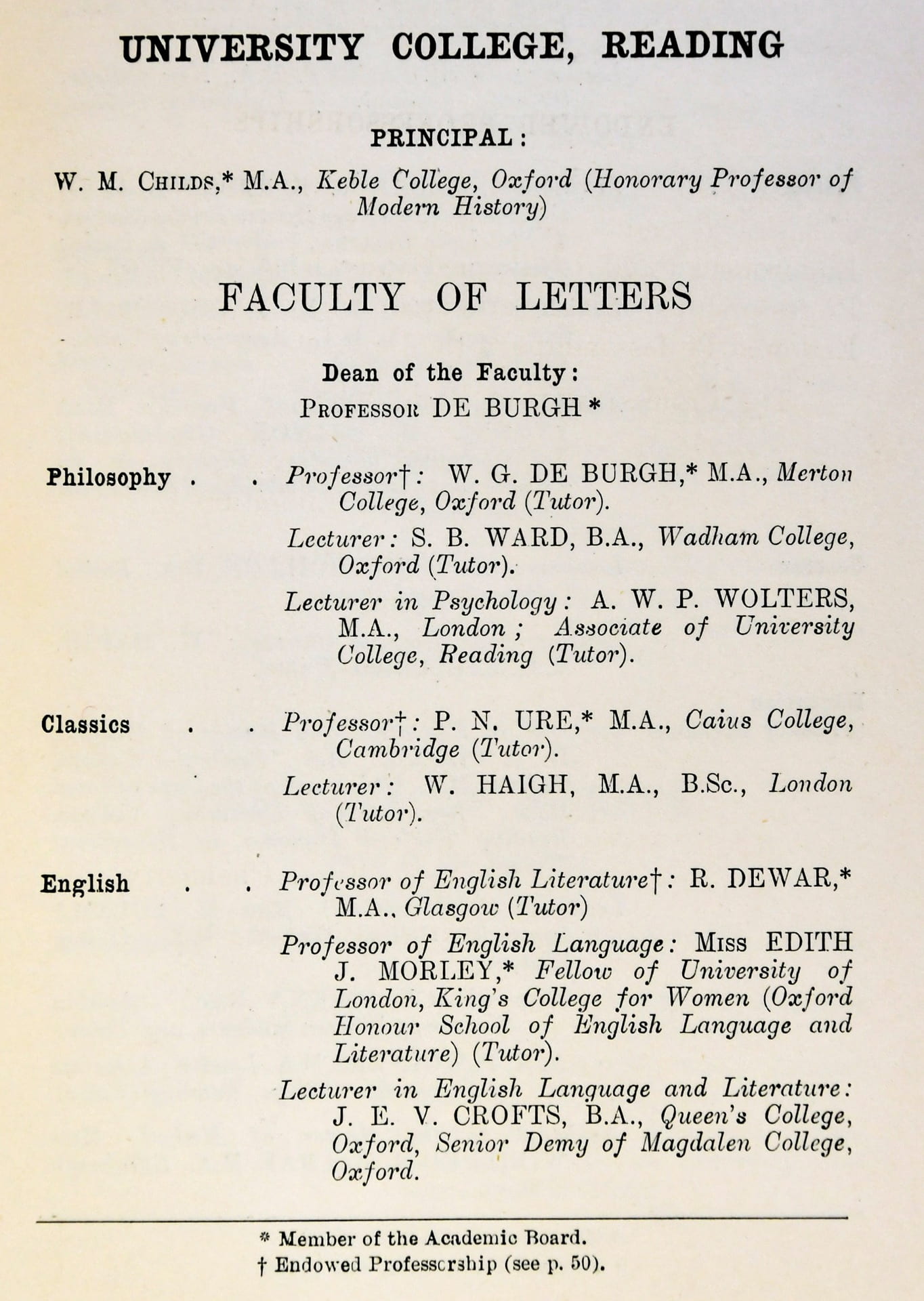

By 1911 the appointment of a Professor of English Literature was imminent. A Mr J. E. V. Crofts had recently been appointed Lecturer in English Language and Literature and, according to Childs’s handwritten notes, this new appointment would ease his workload.

In the meantime it is apparent that there had been attempts by Morley to renegotiate her position in the light of the impending appointment. The evidence for this is contained in a typed ‘private’ letter from Childs to Morley of 4th June 1912. In it, he stresses that he is not prepared to consider any change to their previously agreed arrangements, including the wording of her title. He wants her to stay but the half-time arrangement on a salary of £300 will not change. There is no prospect of the money increasing for a half-time contract and there is no chance of her becoming full time. Apparently she has told him that she had ‘prospects elsewhere’.

Further correspondence (Morley to Childs, 4th & 17th June 1912) shows that Morley is still deeply unhappy with the title of Professor of English Language. She has taken advice from elsewhere, however, and will agree to the title even though she regards it as anomalous (in her reminiscences, she refers to English Language as, ‘the branch of my subject in which I was not and had no intention of becoming a specialist’). Furthermore, she will keep to their agreement of 1908 even though her being half-time would compromise the equality of the two professorships.

Up to this point, I have had nothing but admiration for Edith Morley and her achievements, as must be clear to anyone who has read the many references to her in this blog. Nevertheless, even I have to concede that she committed a serious tactical error in a letter of 17th June by including the following statements that, in my opinion, clearly conflict with the 1908 protocol:

‘If the post is given to a man, however promising, whose achievement is at present small, while in standing, teaching & other experience he is much junior to myself, I cannot accept his “authority in (literature) matters which concern us both”, but shall have to resign at once. I do not demand impossibilities, but the field is limited, & everything depends on the candidate selected.’

This apparent attempt to impose conditions on the new appointment did not go down well. In a letter of 18th June, Childs reminds her of their earlier agreement and points out that the College Council has a free hand to appoint any suitable candidate. He complains, ‘You raise fresh difficulties or prospects of difficulties at every turn.’ He feels unable to proceed with a previous arrangement that she is now trying to change and must be free to propose a new settlement.

Realising she has gone too far, Morley penned a retraction on 19th June: ‘My letter seems to have conveyed exactly the opposite impression from that which was intended.’ She insists that she intends to make the conditions of 1908 workable and wants Childs to give up the idea of replacing the old agreement.

The following day (20th June), she again writes that she is happy with the conditions of 1908 and wants this letter substituted for the one of the 17th. Nevertheless, Childs insists on forwarding both sets of correspondence to the Finance Committee.

The dean intervenes

On the same day (20th June 1912), Professor W. G. de Burgh, Dean of the Faculty of Letters, sent out a memo in which he claimed that Morley lacked the qualities necessary to lead such an important department and recommended a revision of the 1908 agreement, something he had never been happy with.

Her recent letters to Childs simply demonstrated her lack of judgement and discretion. He believes she could retain her title but should be unequivocally subordinate to the new Professor. Otherwise there was a danger that she might assume an albeit unofficial leadership of the women members of the College!

June 1912: The finance Committee’s verdict

The Finance Committee issued its report on 21st June 1912, and its decision was passed on to Morley in a letter from Childs on the 22nd June. There were three main points:

-

- There should be a ‘fair trial’ of the agreement of 1908; Morley would remain half-time.

- If the arrangements did not work they could be modified.

- When the College became a university, the Council would have the right to make a single professor responsible for the whole subject of English language and Literature.

Morley immediately sought clarification of the third point (22nd June), but Childs insisted that it spoke for itself and refused to elaborate (24th June).

July 2012: Professor R. Dewar is appointed

The appointment Robert Dewar as Professor of English Literature was made in July 2012; Morley was not impressed:

‘I abstained from voting for Mr Dewar because I object in principle to the appointment to so important a post, of a man who has not yet proved himself.’ (Morley to Childs, 19th July).

In the belief that she would lose her position when the College became a university she enclosed a formal letter of resignation. She says she intends to apply for a Readership at King’s College for Women and asks Childs for a reference.

Subsequent events unfold as follows:

-

- Childs protests about her taking such drastic action, claiming that she has made an ‘unauthorised’ and ‘unwarrantable assumption’ about Point 3 of his letter of the 22nd June. He is returning her resignation letter and advises her to await the outcome of her King’s application before finalising her decision (19th July).

- In a letter from Morley to Childs on the 24th July she has changed her mind and states that she has ‘definitely decided not to stand for King’s.’

- In a reply dated the 25th, Childs is glad she is staying but fears there may be future conflict. She must therefore commit herself wholeheartedly and ignore the setbacks. If she can’t do this she should go to King’s.

- In a response of 26th July, Morley agrees that she had misconstrued Point 3 of the Finance Committee’s decision, mistakenly believing she would be forced to leave when the Royal Charter was granted. She will accept the risk and hopes to stay on permanently.

- Morley to Childs on the same day: Childs has now returned her resignation letter. She will forget her grievances, she says, and affirms that: ‘I think you will agree that my decision to give the new conditions a trial after all that has passed, is the best proof I can offer that I am putting my “dignity” on one side.’

The New English Department

At the beginning of the autumn term 1912, the College calendar displayed the full complement of the English Department: two Professors – one for Language and one for Literature, and one Lecturer in both Language and Literature (see below).

As had been requested by Morley in 1908, her title is no longer Professor of English Language and Lecturer in English Literature but simply Professor of English Language. This, she believed, would remove any impression that she was subordinate to her new colleague.

Professor Dewar and Mr Crofts were soon to join the armed forces, returning from WW1 as late as February 1919. Presumably Professor Morley kept the department going during their absence. In 1934 Dewar succeeded W. G. de Burgh as Dean of the Faculty of Letters and held that post until 1948.

Sources

Holt, J. C. (1977). The University of Reading: the first fifty years. Reading: University of Reading Press.

Morley, E. J. (2016). Before and after: reminiscences of a working life (original text of 1944 edited by Barbara Morris). Reading: Two Rivers Press.

University of Reading, Special Collections, MS 2049/50: File of correspondence between William M. Childs & Edith Morley, including a memo from W. G. de Burgh.

University of Reading Special Collections, MS 5305: Photographs – Portraits Box 1.

University College, Reading, Annual Report and Accounts, 1918-19.

University College, Reading. Calendar, 1912-13.