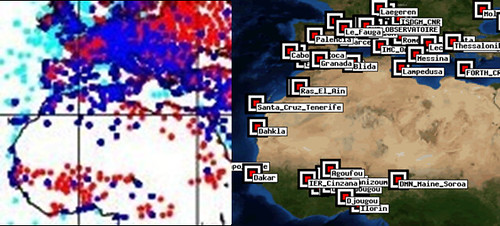

During June 2011 I was involved in some long-awaited fieldwork in Africa. The purpose of the fieldwork was to obtain measurements of the sparsely observed Sahara Desert (see image showing locations of synops and AERONET stations) in order to better understand Saharan climate. In particular, we want to understand how the Saharan heat low develops during summer and how wind blown desert dust may affect its development – for example, through radiative forcing. Better understanding of all these processes should improve NWP and climate models.

Left – locations of synoptic stations over North Africa, right – locations of ground based AERONET stations measuring aerosol optical depth in North Africa

To this end, a huge amount of effort had been put in by many universities to set up two supersites in the desert, making a range of ground based measurements (such as lidar, dust, sodar and radiosondes), and a dozen automatic weather stations dotted around the western Sahara, pretty much in the middle of nowhere.

The icing on the cake was to be airborne measurements made by the FAAM BAe146 aircraft (jointly owned by NERC and the Met Office). The aircraft would be able to sample specific weather and dust events which were being forecast by models or seen in satellite images in real time.

The FAAM BAe146 atmospheric science research aircraft in Fuerteventura

During the field campaign, planning starts around 2 days before a flight (day -2). At this stage we (the ‘mission scientists’) are looking at weather and dust forecasts, to try and see what sort of weather and dust storms might be on their way to the region we have permission to fly over. This turns out to be incredibly difficult for North Africa in the summer time. Weather tends to be dominated by large mesoscale convective systems (MCSs), which are not at all well forecast. Dust is often picked up by strong downdrafts from these MCSs, which means that both dust and cloud forecasts are quite unreliable. Thus on day -2, we end up looking at forecasts and making our best guess as to where to fly, and sketching out a rough flight plan.

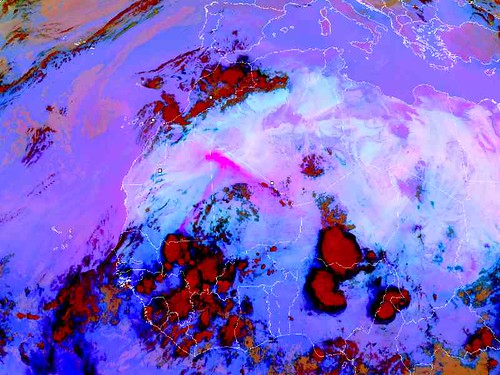

On day -1, we have to submit our flight plan by midday. This means an early start to check whether the forecasts have changed overnight (and rapid re-planning if they have!) and a look at the satellite images, as by this time we may be able to see large clouds or dust storms on their way towards us. (For example, see the ‘pink dust’ over Northern Mali in the image) We’ll have discussions with the pilots to work out exactly how much flying time we’ll have, depending on how far we want to go, the altitudes we’ve chosen to fly at and the order of the manoeuvres we want to do. For example, doing ‘orbits’ (360 degree turns in the air at a banking angle of 60 degrees), may only be possible at the end of the flight when the aircraft has used up most fuel and is lighter. The campaign operations manager will submit our flight plan to the authorities, and usually means notifying them that we’ll be doing special manoeuvres within a certain grid box, roughly 1 by 2 degrees in size. This is typically over the desert in the middle of nowhere, and therefore not a problem.

Satellite image of North Africa, showing high cloud in red and dust storms in bright pink. Note the intense dust plume over Northern Mali.

Once the flight plan is submitted we have a chance to consider the campaign logistics, such as how many flying hours we have left for the campaign, how many more hours the pilots can fly before they need a day off, which instruments on the aircraft need work and therefore time with the aircraft on the ground, and when engineers and instrument operators will need a day off. And the chances are that any plans made will not fit in with whatever the weather does, and will have to change at the last minute!

When day 0, the day of the flight arrives, it’s an early start. The airport opens at 7am, which means earliest possible take-off is 8:30am because the aircraft instruments require time to get going. We mission scientists will be up well before this to check up on the satellite images to see what happened overnight, and to check that our weather feature of interest has ended up in the grid box we got permission to fly in. If not, we’ll be talking sweetly to the pilots to see if they can change our flight location at the last minute, and more often than not they’ll manage this, albeit rolling their eyes at the meteorologists who cannot get their forecast right. Clearly this is a good reason to be trying to improve Saharan African weather forecasts!

Finally we’ll take off and transit at high altitude to our region of interest where we’ll be doing exciting flying close to the desert surface (and a chance to see camels and some amazing desert formations), performing vertical profiles to measure the Saharan boundary layer and dust vertical distribution, dropping radiosondes, and more flying at high altitudes to measure radiative fluxes. Flights last around 5 hours, and will generate masses of data which we’ll be poring over once we get back to the UK. If it’s a day with a ‘double header,’ we’ll have two flights in a row, with a change over of pilots in between to make sure they don’t work for too many hours. Doing a double header allows us to follow the meteorology as it changes during the intense diurnal cycle over the Sahara. It’ll be about 8pm by the time we land, and about 9:30pm by the time we get back to the hotel – time for a quick dinner before the next day’s flight for the instrument operators, and time to catch up with the ground planning team for the mission scientists – and then it all begins again.

Below are photos of some of the amazing desert formations we flew over. The things sticking down from the aircraft wings are aerosol and cloud probes.

A dried up river bed with some plants groing in it

Sand dunes