By Bill Collins

Aerosols are fine particles or liquid droplets suspended in the air. They originate from many sources – both natural (desert dust, sea spray) and man-made (power stations, traffic). They generally act to cool the climate (a good thing); but are very bad for health and the environment and so pollution policies are aimed at cleaning up these particles. We now know that increasing atmospheric aerosol loading has offset some of the warming from carbon dioxide emissions over the last century or so. The world would be warmer today without them, but how much warmer? This matters, because most predictions for the second half of this century suggest that pollution from man-made aerosols will be dramatically reduced, potentially unmasking the full force of the warming from rising levels of carbon dioxide.

If the observed warming of 0.85°C (over the period 1880 -2012) is made up from warming from carbon dioxide countered by cooling from aerosols, the larger the cooling has been, the larger the warming from carbon dioxide must have been – and vice-versa. The latest IPCC Fifth Assessment Report has decreased the estimate of the effect of aerosols since the Fourth Assessment Report in 2007. The climate effects are quantified as the global average change in the energy flux (radiative forcing) in Watts per square metre (W/m2). The radiative forcing from aerosols was assessed as -1.2 W/m2 in the Fourth IPCC Assessment but -0.9 W/m2 in the most recent Fifth Assessment. So does this mean that the sensitivity of climate to carbon dioxide is less than previously thought? Some have suggested so, but this then disagrees with other estimates of climate sensitivity such as those derived from climate changes in the geological record.

Not all Watts are equal, or at least have an equal effect on warming or cooling. Aerosols don’t last long in the atmosphere before being washed out by precipitation. This means that the aerosols from man-made pollution are most abundant close to industrialised regions in northern mid-latitudes. In contrast, carbon dioxide is very well-mixed within the atmosphere, with a lifetime measured in centuries or even millennia. A recent study by Drew Shindell at NASA (Shindell 2014) has found that aerosols from industrial pollution have a 50% greater “efficacy” on climate than carbon dioxide does. This is mainly because the temperature change from each W/m2 in the northern mid-latitudes seems to be larger than for a W/m2 in the southern hemisphere.

So aerosols seem to be more important again, and hence the climate sensitivity to carbon dioxide is likely to be higher in order to have compensated. While this brings back consistency to our estimates of climate sensitivity it is bad news for the future, since cleaning up the man-made aerosol load may well result in the climate system being exposed to the unmitigated extent of the tropospheric warming from rising CO2 levels.

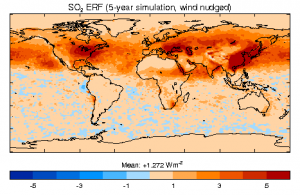

The University of Reading is collaborating within the European project ECLIPSE better to quantify the climate response to aerosols. Preliminary results (see Figure 1 below) seem in line with the Shindell findings. Cleaning up the aerosols leads to a positive radiative forcing which is strongest over the northern mid-latitudes, particularly the industrialised regions of North America, Europe, and East Asia. The warming response is greatest in the northern hemisphere and is amplified in the Arctic due to reductions in snow and ice cover.

Figure 1. Effective radiative forcing (top) and temperature response after 50 years (bottom), from cleaning up all man-made sulphate aerosols. Preliminary results from the HadGEM3 climate model. Strong changes in the Barents Sea and north of Iceland are from fluctuations in the modelled sea ice that may just be natural variability.

Shindell, D., 2014. Inhomogeneous forcing and transient climate sensitivity. Nature Climate Change, 4, 274-277 DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE2136