By: Peter Cook

One of the big discoveries of recent decades has been the finding of thousands of exoplanets, and it now seems that most stars have planets. Remarkably, detailed measurements have now been made of some of these despite the huge distances involved. The first two exoplanets to have their atmospheres studied in detail, and their spectra directly observed, are HD209458b (also called Osiris) at a distance of 159 light years and HD189733b (having no other name at present) at a distance of 64.5 light years. Both are large planets, similar in size to Jupiter and mostly composed of hydrogen and helium. They orbit very close to their stars so are referred to as being “Hot Jupiters” (many of the exoplanets found so far are Hot Jupiters, though this is probably a selection effect as such planets are the easiest to find).

Osiris was first found using the motion of its star (as both go around a mutual centre of gravity) which revealed its mass, and then again when it transited its star (revealing its size). Osiris is only 0.047 astronomical units (AU) from its star (one AU is the average distance between the Earth and Sun) and orbits in only 3.5 days. While roughly similar in mass and radius to Jupiter it has a very low density (0.37 times that of water), and since its star is slightly more massive and brighter than the Sun Osiris has probably been inflated by violent heating of its outer atmosphere. By studying changes in the total infrared emission from the planet and star, as Osiris hides part of the star during transit and is then eclipsed by the star, the temperature of the atmosphere was revealed to be around 1400 K by the Spitzer Space Telescope. The spectra obtained seems to show a dry atmosphere containing sodium atoms and silicate particles, while high-precision observations by the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope and the CRyogenic high-resolution InfraRed Echelle Spectrograph (CRIRES) measured gasses streaming from the day to night side at a speed of around 7000 km/hour (Osiris must be tidally locked and so keep the same side facing its star). Further measurements imply that Osiris is very dark in colour, reflecting less than 10% of visible light, and has patchy high-altitude hot clouds composed of metal oxides. Osiris is surrounded by an envelope of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen, more than twice the size of the planet, with a significant tail pointing away from the star. This was discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope Imaging Spectrometer by measuring star light passing thorugh it and shows mass lost from the planet and blown away by its star. Osiris has probably lost a few percent of its mass over its lifetime.

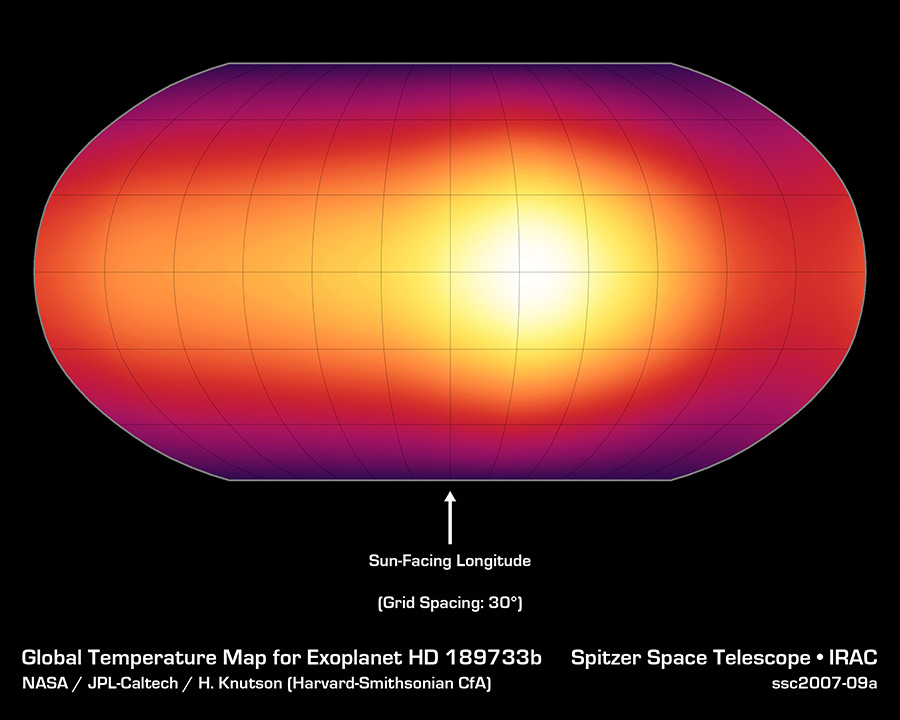

HD189733b was also found using both the transit and radial velocity methods, only 0.031 AU from its star and orbits in 2.2 days (though is not quite as hot as Osiris since its star is less massive and fainter than the Sun). Observations by the Spitzer Space Telescope over 33 hours were used to create a temperature map (see figure). These are in the range 973-1212 K with the peak offset 30 degrees east of the sub-stellar point (again the planet must be tidally locked) showing that absorbed energy is distributed fairly evenly through the atmosphere and hence wind speeds would be of order 8700 km/hour. Again, the atmosphere seems to be fairly dry; sodium has been detected (3 times the concentration as at Osiris) and carbon dioxide. Visible light polarimetry shows that HD189733b is blue in colour (unlike the very dark Osiris), probably due to Rayleigh scattering of blue light in the atmosphere and the absorption of red light by molecules. An X-ray spectrum of the planet’s transit (H1 Lyman-Alpha) shows an extended exosphere of hydrogen and hence a slow evaporation. Some further measurements indicated the presence of water vapour and methane in the atmosphere (though these should quickly react together in the high temperatures to form carbon monoxide), and silicate particles (in which case, HD189733b could have rain consisting of molten glass!).

This information is from Wikipedia, and the Spitzer Space Telescope map was also found online.