Growing up in Europe late last century, I would have been a little surprised at this question, and my knee-jerk answer would have been a firm no: hurricanes happened on TV in far-away tropical places, bending and breaking Caribbean palm trees, but not European oaks.

Some thirty years later, I have learnt that this question is worth unpicking a little more. It is true that most North Atlantic hurricanes form over the ocean at low latitudes before travelling west or northwest primarily making landfall over North America’s Gulf and Atlantic coasts where they can cause damage through the strong winds and rain they bring. Some hurricanes do however recurve into an eastward path and eventually reach Europe (Figure 1). They change as they do so, losing the characteristic eye, tending to weaken, and developing warm and cold fronts. In short, some (ex-)hurricanes reach Europe, but they are no longer hurricanes when they do.

Figure 1: Path and lifecycle of Hurricane Katia (August/September 2011).

Recent work at the University of Reading and the National Centre for Atmospheric Science has given us a better idea of how often such storms affect Europe, what properties they have, how damaging they are, and what factors control their incidence. Baker et al. (2020) show that these so-called post-tropical cyclones (PTCs) are rare; about two PTCs make landfall in Europe per year on average with some years seeing none at all and more than five landfalls in other years. Interestingly, in a minority of these storms, aspects of their tropical origin can be recognised even as they make landfall in Europe, and it is these storms that are the windiest PTCs to reach Europe.

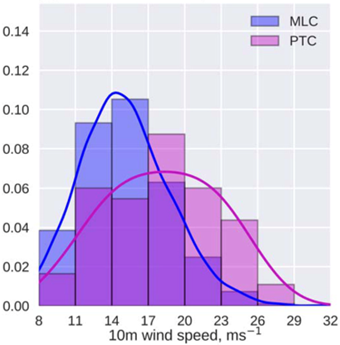

Given PTCs are so rare, one might argue that they are a curiosity but not overly important as a source of hazardous weather affecting Europe. To assess their importance fairly, PTCs need to be put in the context of the hundreds of midlatitude storms that affect Europe each year and do not originate in the tropics. This is one of the issues addressed by Elliott Sainsbury, SCENARIO PhD student at the University of Reading. Elliott and his colleagues have shown that, while only about 1% of all storms affecting Europe are PTCs, they constitute about 8% of the systems attaining storm-force winds (Sainsbury et al 2020, Figure 2).

Figure 2: (left) Normalised frequency of post-tropical cyclones (PTCs) and, other, midlatitude cyclones (MLCs) affecting Europe and attaining a given surface windspeed, and (right) the fraction of all storms which are PTCs and attain a given windspeed

In other work, they determined what controls the large variations in the year-to-year number of PTCs (Sainsbury et al. 2022). They show that the number of hurricanes recurving and entering the midlatitude North Atlantic in each year is primarily determined by the total number of hurricanes forming in the tropical Atlantic in the first place. This latter number, also called the activity of the hurricane season, can be predicted with some skill ahead of the season as it is controlled by large-scale and predictable modes of climate variability such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon. The results by Sainsbury et al. 2022 are therefore encouraging, as some of the seasonal predictive skill might extend to PTCs affecting midlatitude regions such as Europe.

Finally, it is logical to ask if the number or character of PTCs affecting Europe will change with global warming. The answer is, alas, not known. There is indeed some concern that more of these storms might reach Europe as the North Atlantic Ocean warms (Haarsma et al. 2013), yet climate model simulations do not agree on the future change – Elliott’s ongoing work shows that most models project an end-of-century decrease in the number of North Atlantic hurricanes offset by an increase in the fraction of hurricanes reaching the midlatitudes as PTCs. Crucially, the latest generation of models cannot be trusted to fully capture the physical processes controlling the character and trajectories of hurricanes, and further research and climate model development are needed to address this question with any degree of certainty.