There are two main paternity assurance strategies which are generally found in birds: mate guarding and frequent copulations. The latter is expected particularly in species such as raptors that cannot guard their mates efficiently because of ecological constraints, such as frequent courtship feeding. An experiment investigated the prelaying behaviour of red kites, in which the males undertook courtship feeding. The study compared pair behaviour in situations of varying breeding density and simulated male territorial intrusions by presenting decoys.The results showed that males’ certainty of paternity was likely to decrease with increasing breeding density because of the proximity of other males and more frequent male territorial intrusions during the presumed fertile period.

The percentage of time spent by males within their breeding territory during the prelaying period was positively related to the number of close breeding neighbours, suggesting territory surveillance and mate guarding. Copulation frequency prior to and during laying increased with breeding density, and in isolated pairs in response to simulated male territorial intrusions. These results support the idea of paternity assurance through frequent copulations during the presumed fertile period of the female, and suggest that early copulation activity is related to functions other than fertilization, such as pair bonding or mate assessment (Mougeot 2000).

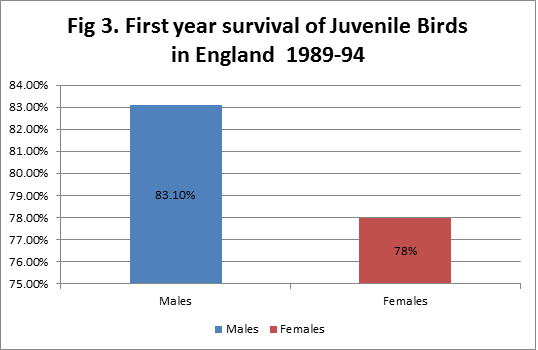

In an attempt to extend the breeding range of the Red Kite within the United Kingdom, 93 juvenile Red Kites, originating from Spain, Sweden and Wales, were released in southern England in 1989–94 (Fig 1), and 93 juvenile Red Kites, originating from Sweden, were released in northern Scotland in 1989–93 (Fig 2). Minimum estimates for first-year survival were 83.1% and 78.0% for male and female Red Kites in England (Fig 3), and 50.0% and 52.5% in Scotland, respectively (Fig 4).

Annual survival then improved in the second and third years. Several sick or injured birds were recaptured, treated and returned to the wild, and some of these eventually bred. In their first year, birds released in Scotland tended to disperse greater distances than those released in England, females travelled further than males, and birds released during the early years dispersed further than those released during the later years. Successful breeding started in 1992 in England and Scotland. The mean age of first breeding was 1.9 years and 2.6 years for males and 1.8 years and 1.7 years for females in England and Scotland, respectively (Figures 5 and 6).

Demographic parameters were used to construct deterministic models for population growth. At current rates of growth, it is predicted that the English and Scottish populations will exceed 100 breeding pairs by 1998 and 2007, respectively (Evans et al. 1999).

Reference List:

- Evans.M.I., Summers.R.W., O’Toole.L., Orr-Ewing.C.D., Evans.R., Snell.N., & Smith.J., (1999) Evaluating the success of translocating Red Kites (Milvus milvus) to the UK. Bird Study, 46, 129-144.

- Mougeot.F., (2000) Territorial intrusions and copulation patterns in red kites,(Milvus milvus), in relation to breeding density. Animal Behaviour, 59, 633-642.

Hi Thomas,

I am interested to know where one can find a red kite decoy. Do you have to make your own?

David

Dear David

I believe for this study, the researchers made their own decoy, which was a plastic model painted with the same plumage as a Red Kite, and smaller in size than a female in order to mimic a 2 year old male bird.

There is definitely potential for a market in Red Kite decoys though!

Thomas Whitlock