By Chelsey Geralda Armstrong

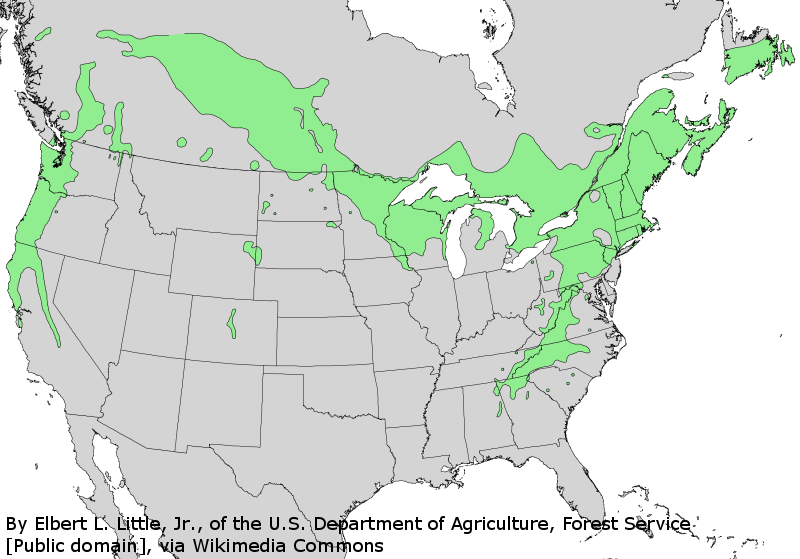

On Day 4 of the advent botany series this year we heard about the world’s 4th largest nut crop, the European Hazelnut (Corylus avellena). But, it’s poorly known cousin in the Pacific Northwest of North America, the beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta), is also a classic Christmas favourite! The name ‘cornuta’ means ‘horned’, appropriate for this species.

Beaked hazelnut produces a slightly smaller nut but can grow up to ten meters high. The Yurok Indigenous people of California still burn hazelnut to encourage the growth of young, straight shoots used in weaving. First Nations in British Columbia used slightly older shoots for making projectile shafts and other tools. The root was boiled to produce a blue dye, oily shells were used to keep fires burning and the nut was eaten or roasted and its oil rendered for chest and lung medicines. At one point, hazelnuts were an important currency in Southern British Columbia and a large sack of hazelnut was a typical bride price!

Although hazelnut is considered a wild shrub, ethnobotanists have been working with Indigenous people on documenting the ancient and recent management of sgan t’sek (hazelnut in the Gitxsan language). This “wild” shrub was likely managed using fire, coppicing, and was transplanted long distances – effectively creating little human-made hazelnut patches throughout Western Canada. One disjunct population in Northern British Columbia grows exclusively on old archaeological sites and in pairs, with another local favourite, native Pacific crab apple (Malus fusca).

After settler-colonial contact and widespread missionary work throughout British Columbia, a synchronicity of Indigenous practices exploded out of the resistance or adaptation to European traditions. Nlaka’pamux Elder, Marion Dixon remembers sewing little bags that were stuffed with local hazelnuts, and walnuts her grandfather bought from the store. A candy was placed on top of the bag and under the tree it went, “that’s all we ever got for Christmas, maybe some shoes if you were lucky.” During the Christmas celebrations Marion also remembers her grandmother crushing up the nuts to make a coffee-like drink. Darlene Vegh from Gitxsan territories told us it was the children’s duty to collect nuts in the fall, they would store them in the attic to let the involucres (green husk-like firs), rot off and by Christmas they were ready to go!

When discussing the hazelnut harvests in Northern British Columbia, most people lament how the squirrels seem to “get there first”. Indeed, between August and September hazelnut groves are absolutely teeming with squirrels! When asked if the squirrels disturb his hazelnut harvest, one Gitxsan Elder replied “they don’t bother me they help me!” – he would wait for the squirrels to clean the involucres aggregate and bury them, then raid their caches throughout the year.

So if you’re looking for a fun activity over the holidays, find a nice hazelnut grove and start poking around for a hard-earned Christmas treat!

Advent Botany 2015 Day 16, Day 18

Index to Advent Botany 2015

Pingback: Advent Botany 2015 – Day 17: Sgan t’sek « Herbology Manchester

Pingback: Advent Botany 2015 – Day 18: The Tangerine – Just Like a Virgin | Culham Research Group

Pingback: Tendrils: 151218 – The Unconventional Gardener