For me, the glace cherry is a staple ingredient of Christmas cooking. I include them in both my Christmas cake and Christmas pudding recipes – both are based on ‘Delia Smith’s Christmas’ although her original version of the pudding recipe does not have cherries in.

Cherry in English derives from the French ‘cherise’ which in turn comes from ‘cerasum’, the Latin for cherry which refers to the geographic origin of cultivated cherries; Kerasous ( Κερασοῦς, an ancient Greek name for Giresun in modern day Turkey). Some cherry species have this name embedded in their scientific name (e.g. Prunus cerasifera, Prunus cerasus, Prunus cerasoides) but, rather ironically, not the sweet cherry of cultivation!

Glace cherries usually have a very artificial look to them due to the bright colour, transparency and rather stiff texture however they are real fruit even if they don’t count as part of the 5-a-day. Despite their artifical appearance, the glace cherry comes from a beautiful and widespread Eurasian tree species valued for it’s beautiful spring flowers and warm reddish timber.

The Wild Cherry

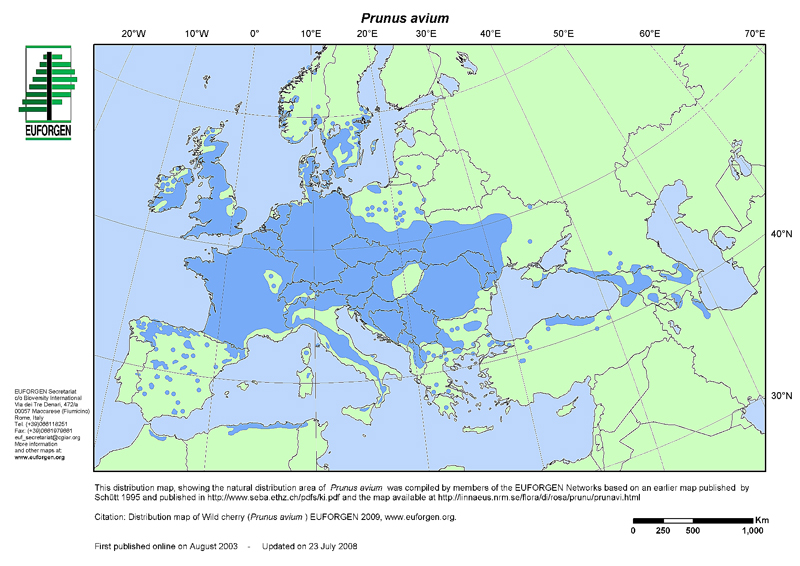

Sweet cherries are from a fast growing tree species called Prunus avium (Wild cherry) that is native to Britain, the rest of Europe and extends much further east (see map below). In Britain, widespread planting means that it’s possible to find wild cherries almost anywhere. Prunus avium generally grows 10-20m tall but can reach up to 30m in height. It is quite short lived, generally only about 60 years. It has shiny bark and profuse white (or pale pink) blossom in the spring. It’s timber is fine grained and the heartwood is reddish. It is often used as a veneer on furniture.

One of the quick identification features when the tree is in leaf are the two red glands on the leaf stalk (below). The wild species produces quite small but fleshy fruit with a large stone in the centre.

- Paired red nectar glands (circled in blue) on the leaf stalk

- Wild Cherry in flower

- Wild cherry fruit

Cultivated Prunus avium

The origin of the cultivated cherry may be as recent at 3000BP (Zohary et al. 2012) because selected clones can only be propagated by grafting. However the wild cherry does reproduce by suckering and it is not clear to me why earlier civilizations could not have reproduced trees in this way. Selection over many years has resulted in a wide range of cultivars that are much larger fruited than the wild species. Wild sweet cherries were certainly eaten by hunter-gatherer civilizations and archaeological remains show that Neolithic people ate wild cherries. The first reliable reports of cultivated sweet cherry are from Pliny reporting to Lucullus the arrival and cultivation of a superior form of sweet cherry in the first century BC. Sweet cherries were introduced into England by Henry VIII who had them planted at Teynham in Kent. He’d tasted them in France.

Modern cultivars

Glace cherries are made by a lengthy process of of boiling, bleaching, dyeing and infusing with sugar. Step 1 is to boil the cherry for a short while to make it more permeable. Step 2 involves bleaching with sulphur dioxide while the structure of the fruit is maintained with a calcium solution. Step 3 is to infuse the cherries with sugar by soaking them in a gradually increasing concentration of sugar syrup, at the same time adding a colourant to restore the red (or to make them green or yellow!). Common cultivars used for glace cherry production are ‘Bing’, ‘Dawson’, ‘Rainier’ and ‘Royal Ann’. If you don’t like the idea of bleached and re-dyed glace cherries, you can always make your own from fesh cherries.

Maraschino cherries are also preserved but in a different way. The original Maraschino cherries were the variety Marasca from Croatia, where they were preserved in a cherry liquer but modern cocktail cherries, most commonly called maraschino cherries, are preserved first by soaking in brine or a solution containing sulphur dioxide and calcium salts to preserve them and then infused with a sugar syrup (often corn syrup) and dyed red. Modern maraschino cherries are commonly flavoured with almond extract.

In many ways it’s lucky that neither glace nor Maraschino cherries have the stones remaining – the world record for cherry stone spitting is 28.51m, by Brian Krause of Eau Claire in Michigan, and it would not be a pleasant accompaniment to your Christmas celebrations to be dodging the hard stones!

Do put a cherry on the top!

Pingback: #AdventBotany 2018, Day 1: Put a Cherry on the Top! — Culham Research Group « Herbology Manchester

Pingback: Botanical University Challenge 2019! | Dr M Goes Wild