Three years after the decision at at the International Botanical Congress in Melbourne (July 2011) to give botanists and mycologists the option of writing new species descriptions in Latin OR English (ICN Article 39.2) the press seem to have noticed the change (BBC News: New plants will no longer have Latin descriptions). Concern has been expressed at the loss of Latin. However, as a practicing plant taxonomist who did not have the opportunity to study Latin at school and who has seen a steadily dwindling number of colleagues with enough Latin to form a description I am not at all convinced that this change is one we should mourn – and this is why…

Firstly, the adoption of an absolute requirement for Latin descriptions in 1935 replaced an effective free for all where any language was allowed (even though Latin was encouraged from 1908 onwards). This is not the first time therefore that English descriptions have been permitted. In fact the eighth edition of Phillip Miller’s Gardeners’ Dictionary, published in 1768 and famously written in English, was one of the key places of publication of new plant names of the time. It listed the extensive plant collections of Chelsea Physic Garden and other plants in cultivation in the UK. A search of the International Plant Names Index yields over 1500 names attributed to Miller.

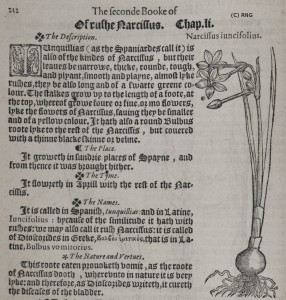

Narcissus jonquilla from Lyte’s ‘A niewe Herball’ of 1578. A recognizable latin binomial accompanied by a decription in English (Admittedly translated from original Dutch via French!)

Secondly, the use of Latin as the international language of science is in the past. Latin was chosen for use as something every educated person would be able to read – an open international form of communication. It has lost that value. Latin was displaced by a form of international English many years ago and scientific publication is strongly dominated by the English language. English is the official language of more countries than any other single language (although it does not have the largest number of native speakers, coming third after Mandarin then Spanish). Five of the world’s 10 largest Herbaria (scientific dried plant collections) are held in English speaking countries (the others in France, Russia, Switzerland, Austria & Sweden) and the formal code that governs the naming of plants and fungi (ICN, 2012) is written in English. Perhaps, as a native English speaker, it is easy for me to accept a change into a language I speak anyway, and that I might resist if I did not speak the language.

Thirdly, Latin remains an option for new descriptions – it has not been replaced. And the use of Latin names remains sacrosanct even though the etymology of many of them has little to do with Latin in its classical form. For instance the worryingly difficult classification of Hebe led to the genus Hebejeebie being described, and an orchid with black and blood-red flowers looking like a little dragon gained the name Dracula, it’s species including Dracula vampira and Dracula nosferatu. There are many more: Ledermanniella maturiniana (a semi aquatic plant named after Patrick O’Brien’s character Dr Stephen Maturin who kept falling in the water), Macrocarpaea apparata after the apparate spell in Harry Potter books due to the sudden discovery of a 4 m high flowering specimen of this plant from mist on an Ecuadorean hillside after a whole day of searching, and a whole series of fossil plants named after Terry Pratchett characters including Ginkgoites nannyoggiae – which I fear may have a knob on the end.

Finally, the use only of Latin for descriptions effectively excluded many active plant hunters from naming the species they discovered, giving nomenclature an exclusive and stuffy reputation. Surely it is better that those who have discovered the plants in the field have a fair chance of naming them?

So botanical Latin is not really Latin at all, it is just a language that follows the conventions of classical Latin and then cheats by incorporating modern words and making them look exotic. There is no current plan to abolish the use of Latin form in scientific names – it would make them impossible to distinguish from common names – so botanists will not lose the chance for fun and word play. What has become optional is the slog of trying to form a Latin diagnosis, get a competent scholar to check it, and then know full well that the majority of readers would go straight to the longer and more comprehensive description in English anyway.

Part of my job is to run the University of Reading Herbarium (RNG). I care for TYPE specimens and we have an extensive library of reference books, I direct the MSc in Plant Diversity, a masters course launched in 1969 and celebrating 45 years of continuous running in 2014, and I train a team of PhD students from around the world. I’ve even described a few new plant species 🙂 In the past we had to set aside time for teaching basic botanical Latin – we can now use that time to teach more science, to better understand species, their conservation and diversity. I’d rather our students engaged with promoting botany on Twitter than learning an archaic language that excludes others from the good work they will do.

I’ve published new names with English descriptions since the rules changed. I don’t mourn the option of English in descriptions, it was long overdue.

To me the much bigger change in the Melbourne code was the abandonment of a requirement to PRINT and circulate the new description – botanists can now publish on the web only…. But that is another story.