School Bulletins of Highbury Hill High School, 1977 and 1978 – personal collection. Copyright: Seona Myerscough

School newsletters or bulletins were a common feature of grammar schools, especially in the late-twentieth century. Used to share news with parents, alumni and pupils, communicate important changes, and celebrate the achievements of pupils, the newsletters also communicated a sense of institutional identity. These two covers show scenes from the life of Highbury Hill High School in Islington: girls on their commute, and the taking of school photo, likely to have resulted in panoramic snapshot to be rolled up and taken home. By delving into the history of the school, it is clear that these images served a particular purpose during a moment of potential crisis in the history of the school, by attempting to unite the wider school community and preserve a sense of institutional identity.

Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, local education authorities nationwide began a process of ‘comprehensivisation’, as the tripartite system of technical, grammar, and secondary modern schools was replaced with mostly co-educational comprehensive schools. Critics of the tripartite system saw the selection process for grammar schools as inherently unjust, sorting pupils at age 11 by supposed intellect, and replicating an unequal class system. Yet in some areas, such as Reading and parts of London, single-sex grammar schools persisted. Many girls’ grammar schools prior to comprehensivisation promoted a strong sense of school identity, sometimes rooted in the long historical legacies of such schools as spaces of academic and social achievement for girls.

Such schools were also seen by some pupils, parents, and teachers as spaces in which girls could flourish and be free from unwanted male attention and distraction. Research in the fields of sociology and education in the late-1970s and early-1980s had found that girls benefitted in many ways from the absence of boys in the classroom. Education researcher Sheila Riddell observed that in mixed settings, the dominance of loud male classmates in drawing teachers’ attention meant that girls were at times deprived of support and could easily abandon their work for quiet chats with friends. Harassment and victimisation of girls by boys was also a major concern for supporters of single-sex schooling. These understandings of the benefits of single-sex schooling meant that across the country, some single-sex schools survived the spread of co-educational comprehensivisation.

Highbury Hill High had become a comprehensive school in 1976 after decades as a grammar school, expanding its pupil base from those who had achieved higher results at age 11+ to an intake of varied academic success. This new intake drew in girls from across the bands of the London Reading Test. Some years later, it was revealed that administrators within the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) had an unfortunate habit of reclassifying some top performing girls into lower bands. This was to maintain a truly ‘comprehensive’ intake in co-educational schools but meant that many high-performing girls lost their first preference of secondary school. This tension for local authorities between balancing the egalitarian spirit of comprehensives with the problems girls faced in co-educational spaces proved a difficult issue for educationalists, feminists, and teachers throughout the late-twentieth century.

Highbury Hill was unusually left as a single-sex school, despite co-education generally accompanying comprehensivisation. In the 1977 School Bulletin, the headmistress, Mrs Butcher, commended the successes of the school in adapting to this new mixed-ability intake. Yet she also alluded to tensions, drawing parallels between the academic ability and behaviour of the new comprehensive intake, as she warned newcomers of the ‘self-defeating habit’ of truancy and the danger of future unemployment should such behaviour continue. Conceptualisations of intellect and class fundamentally shaped how teachers saw and interacted with their pupils; many former grammar schoolgirls from working-class backgrounds have reflected on the hostility and elitism they faced from teachers and peers. Such tensions between staff and new pupils had the potential to jeopardise the harmony of the school.

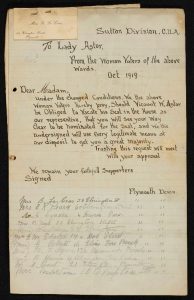

In contrast to the concerns of the Headmistress, the School Bulletin cover of 1977 shows happy, cheerful girls with handbags, bicycles, and a mix of hairstyles heading towards the school, a picture of youthful enthusiasm. Similarly in 1978, the cover shows the taking of a whole school photo, girls cheerfully sat cross-legged in the playground. Both depict moments of social cohesion and school pride. If considered alongside the recent changes to Highbury Hill High and the threat of comprehensivisation to school identity, the images can be seen as representative of the need to unify the student body and project an image of harmony to potentially concerned parents and pupils. The covers were drawn by a pupil from a cohort of exclusively grammar pupils. Whether the representation of unity was encouraged by teachers or not is uncertain, but the decision of the pupil to present a harmonious image of this new mixed student-body suggests the possibility that for pupils, these supposed tensions were less threatening than they were for some teachers.

The illustrations and accompanying newsletter provide a snapshot into the life of one London school, and suggest that while comprehensivisation was regarded as a mission in equalising educational opportunity for all pupils, in some areas it led to unforeseen complications – particularly for girls’ schools. The images on the covers of the School Bulletins represent the efforts of schoolteachers and pupils to unify an ever-changing student body and wider school community, and to preserve the identity of Highbury Hill High School in an era of transformative local and national change.

Amy Gower is a doctoral researcher and sessional lecturer at the University of Reading. You can find her on Twitter @AmyG_Historrry.