While researching the history of gender identity I have come across numerous debates over a variety of issues. Appropriate terminology, categorisation, the genesis of gender fluidity are all hotly contested issues and let’s face it, as historians we love a good debate. One of the most contentious issues is the relationship – or lack thereof – between gender history and the history of sexualities. Scholars such as Jay Prosser have expressed the legitimate concern that combining studies of historical sexuality and gender identity leads to the silencing of gender fluid individuals who become amalgamated into narratives of same-sex attraction or economic necessity. This silencing is particularly prevalent in cases of individuals who presented as male before the advent of sex reassignment surgery. Billy Tipton and James Barry are among the historical figures who have been ‘reclaimed’ by women’s history as ‘passing women’ who adopted male identities to follow their chosen careers and pursue female same-sex relationships.

This antagonism between gender and sexuality is not only an academic concern. A cursory look at LGBT+ activism reveals the frequent marginalisation of transgender, non-binary and gender non-conformity within the movement as a whole. Equally, the countless cases of sexual and physical violence against transwomen speaks to the degree to which the conflation of gender and sexuality can have devastating results. Gwen Araujo’s murder in 2002 by four cisgender men, two of whom she had previously had physical relationships with is a case in point.[1] Their use of the ‘panic’ defence allowed the defendants to misgender Araujo as male, thereby portraying her as a man who ‘deceived’ them into homosexuality.

Gwen Araujo

Araujo’s gender identity was reduced to her genitals by her murderers. Historical gender non-conforming figures often suffer the same fate. Bernice Hausman has argued that transgenderism – or ‘transsexualism’ to use Hausman’s term – cannot exist before the development of sex reassignment surgery.[2] The reconstruction of the genitals is what makes a person transgendered. It is true that the individuals considered in my own research would not have recognised the term transgender or identified with it. However, their personal testimonies mirror modern autobiographical accounts from transgender individuals and their experiences are evidence of gender fluidity that predated surgery and modern terminology. The category of transgender may be a modern construct, but it seems very misguided to assume that a label creates an identity. Hausman’s argument not only ignores the numerous individuals who identify as trans who do not physically transition, but it also returns us to the preoccupation with genitals in determining gender. This begs the question, has the merging of gender and sexuality led to the dominance of genitals in LGBT+ studies?

Despite the array of potential sexual activities, the focus often rests on penetrative heterosexual intercourse which excludes a myriad of experiences. In terms of gender identity, the focus on genitals is even more reductive. As a cis gender woman, the idea that my female gender is solely dependent on my biology is diminishing and misguided; how much more insulting for individuals who are misgendered due to their bodies?

All of the points above suggest that a complete separation between gender history and the history of sexualities is needed. At the start of my research, I was certainly passionate about stressing the difference between gender non-conformity and sexualities, partly due to the constant assumption that transgender history was an offshoot of queer sexualities rather than gender identities. However, I have quickly discovered how frequently the two areas not only overlap but impact on each other. The lives of Roberta Cowell and Michael Dillon, the first trans woman and trans man respectively to undergo sex reassignment surgery are prime examples.

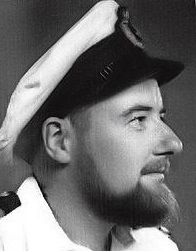

Michael Dillon

Michael Dillon identified as male from childhood. Dillon acknowledged his female physicality and in his early years was compelled to live as a woman, but his gender identity was always unequivocally male. For Dillon, his transition merely enabled him to live more easily as a man without being questioned by outsiders as to his gender. It did not originate his male gender. Dillon’s physical transition also did not influence his sexual preference for women. On the other hand, his inability to father a child led Dillon to avoid any romantic relationships throughout his life with the exception of Cowell who ultimately rejected him. Dillon believed that ‘[o]ne must not lead a girl on if one could not give her children’,[3] and when the only woman whom Dillon felt would understand his experiences refused to marry him he remained celibate.

Roberta Cowell

In contrast, Roberta Cowell’s sexual orientation was inextricably linked to her gender identity. Vehemently homophobic, Cowell stressed her heterosexual attraction to women prior to transition when presenting as Robert, marrying and fathering two children. Following her surgery, Roberta was again heterosexually attracted to men while during the transition Cowell identified as asexual.[4] Clearly then, in certain cases gender and sexuality cannot be completely segregated without losing the nuances of individual narratives.

Dillon and Cowell also demonstrate the importance of a more individualised case study approach to queer histories. As historians the obligation to impose our own interpretations on individuals is often inescapable, particularly where no concrete information remains. The reclaiming of figures as either homosexual or gender variant leads to the construction of rigid categorisations which do not account for the rich variety of identities and sexualities that exist both historically and in the present. The best approach then would seem to be that of any good relationship, where both parties – in this case gender identity and sexuality – are considered in tandem as complimenting one another in the light they can reciprocally shine while maintaining their status as distinct facets of identity.

Amy Austin is a PhD Candidate in History, specialising in transgender history of modern Britain. You can also catch Amy on the podcast Surprisingly Brilliant, discussing transgender identities in 1800s Britain with Susan Stryker and Laurie Metcalf.

[1] Anon., The Murder of Gwen Araujo and the “Panic” Defense, [website], (N.D.), https://www.queersiliconvalley.org/the-panic-defense, (accessed 21 July 2021).

[2] Bernice L. Hausman, Changing Sex: Transsexualism, Technology, and the Idea of Gender (North Carolina, 1995).

[3] Michael Dillon/Lobzang Jivaka, Out of the Ordinary: A Life of Gender and Spiritual Transitions (New York, 2017), 125.

[4] Roberta Cowell, Roberta Cowell’s Story (New York, 1954).