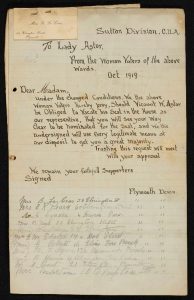

By the seventeenth century, depicting Winter as an old man was nothing new. This painting, taken from a set of The Four Seasons by renowned Flemish artist David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690), was part of an allegorical tradition stretching back to antiquity. The theme was old but the setting and detail were contemporary. In its need to convey symbolic meaning to early modern European audiences, the image can provide insights into cultural assumptions about masculinity and ageing from this period.

Teniers painted several versions of The Four Seasons. He used figures of men, and usually repeated the same allegorical motif for each version: Spring holds a tree to be planted, Summer gathers a wheatsheaf, Autumn raises a glass of wine or spirits, and Winter wears heavy clothing, and warms himself with a brazier. A clear visual clue that the figure of Winter is old is his ‘hoary’ (white) hair and beard. This age signifier was referenced in drama, artwork, and texts. The King James translation of Proverbs 20:29 stated: ‘The glory of young men is their strength: and the beauty of old men is the grey head’.

Using an old person to depict cold, wet Northern hemisphere winters worked on more than one level in this period. Not only was Winter perceived as the final senescent, barren stage of the year, but also old men’s bodies were believed to be constitutionally cold and wet.

According to the dominant Humouralist concepts of the body, the process of ageing gradually used up our life-giving store of good moisture and heat. Eventually, ‘olde folk’ would be left cold, dry in their ‘solid parts’, and clogged up with cold, wet humours such as phlegm. The old man in our painting makes his way through a cold, snowy landscape beside a frozen lake or river, carrying a brazier for warmth. Winter is dressed in thick clothes, with a fur-lined hat. Instantly we can see old age visually related to both coldness and wetness. In medical understandings of the body, however, these associations had significant repercussions for masculinity.

Coldness and wetness were linked to weakness, softness, ill-health… and womanhood. Women’s bodies were believed to be cooler and wetter than men, compounding pervasive assumptions about women’s feebleness and inferiority. Conversely, healthy men in their prime (25-45/50 years) were supposed to be the perfect balance of heat and moisture, often labelled as ‘hot and dry’. Masculinity was consequently linked to heat, fire, and strength, whereas femininity was associated with coolness, water and weakness – especially in art. This meant that, in what Gail Kern Paster refers to as early modern humouralism’s ‘caloric economy’, as men entered old age and began cooling and abounding in cold, wet humours, they essentially started to embody undervalued ‘female’ constitutional properties.[1]

In our image of Winter, the old man is also hunched, diminished in size, and his walking stick suggests lameness – both indicating a loss of manly strength. On his belt he carries a full purse which was probably a reference to widespread beliefs that older people, like women, were prone to ‘covetousness’ and ‘avarice’. The English author Thomas Wright wrote that ‘olde men, and women are consecrated to covetousnes’ because they lacked the ‘force’ of young men to gather more money and goods.[2] The expression on Winter’s face appears apprehensive, with his slightly opened, downturned mouth, and frowning raised eyebrows. Fear was associated with coldness, old age, and women. Emotions were deeply embodied in this period, and doctors believed that a person’s warm blood and lively spirits rushed to their heart when scared or fearful, abandoning the face and limbs and leaving them pale, cold, and trembling. The Dutch physician Levinus Lemnius explained that coldness made men ‘fearefull, timorous and fainthearted… which is a thing peculiar to womenkinde’.[3]

Another unique feature of the figure of Winter is that he is looking backwards, unlike the other three seasons who stare straight out at the viewer into the present. A tendency to look backwards and dwell in the past was thought to partly explain a further non-masculine trait in old men, that of excessive talkativeness, and wanting to share ‘What they have bin, what they have done, what they have had’.[4] Talkativeness was firmly associated with women during this period, and was tainted with connotations of idleness and ‘folly’. Theologian Richard Baxter declared: ‘Women, and Children, and old folks, are commonly the greatest talkers’.[5] The term ‘gossip’ originated from the group of ‘gossips’ or godparents who attended a baptism, and were mostly women.

Yet, it was not all bad news for our figure of Winter and ageing masculinity. In comparison to the other seasons, Winter seems to be affluently dressed, with a fur trimmed coat and hat, and a gold chain. Older men, who had retained their status and their memories, and were ‘sober’ and ‘temperate’, were thought to have access to positive ageing masculine attributes. Authors listed wisdom, good council, and steadfastness as admired qualities which were easier to attain in old age, after the lusts and ‘heat’ of youth had subsided.[6] Richard Steele declared that ‘Youth have usually the large Sails, but Old-age hath the solid Ballast, and therefore doth sail more steadily and more safely’.[7] The ageing ‘male’ stereotype could therefore encompass authority and wisdom, as well as weakness, fear, and miserliness.

While Teniers’ allegorical image of Winter cannot testify as a historical source for a specific individual, event, or lived experience, it does seem to capture expressively the ambivalent cultural attitudes towards older men in Europe during this period. It helps illustrate how the ‘natural’ cooling and weakening of old age could both erode certain early modern masculine traits and give easier access to others during the winter of a man’s life.

Further reading: Shepard, Alexandra, Meanings of Manhood in Early Modern England (Oxford, 2003); Toulalan, Sarah, ‘‘Elderly years cause a Total dispaire of Conception’: Old Age, Sex and Infertility in Early Modern England’, Social History of Medicine, 29/2 (2016), 333-59.; Reinke‐Williams, Tim, ‘Manhood and Masculinity in Early Modern England’, History Compass, 12/9 (2014), 685-93.

[1] Paster, Gail Kern, ‘Unbearable Coldness of Female Being: Women’s Imperfection and the Humoral Economy’, English Literary Renaissance, 28/3 (1998), 420.

[2] Wright, Thomas, The passions of the minde in generall (London, 1604), 38.

[3] Lemnius, Levinus, The Touchstone of Complexions, (London: 1576), 16v.

[4] Steele, Richard, A Discourse Concerning Old-Age, (London: 1688), 47.

[5] Baxter, Richard, A Christian Directory, (London: 1673), 434.

[6] See: Cicero, Marcus Tullius, The worthye booke of old age (London, 1569), 11r.

[7] Steele, Richard, A Discourse Concerning Old-Age, (London: 1688), 108.

Amie is a PhD researcher at the University of Reading. You can find her on Twitter @AuntieAmie