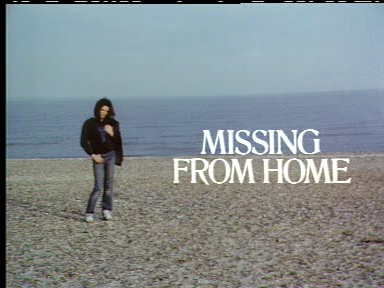

Last February, I had the good fortune to interview one of the great screenwriters of British TV drama, Roger Marshall in his Richmond home. His extensive C.V. has included episodes of The Avengers, The Sweeney, The Professionals, two plays for Armchair Theatre, the serials Missing from Home, Traveling Man and Floodtide. He was also the creator of three series: Zodiac, Mitch and (with Anthony Marriot) Public Eye. In this part of this interview he discusses his 1984 BBC1 serial Missing From Home – an exceptionally successful and popular drama that has subsequently been all but forgotten – and the work of its director, Douglas Camfield:

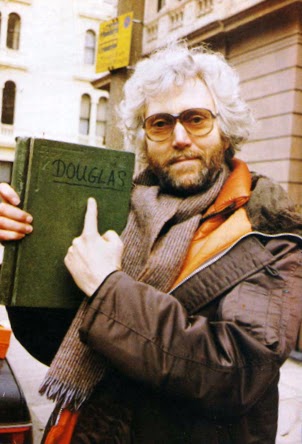

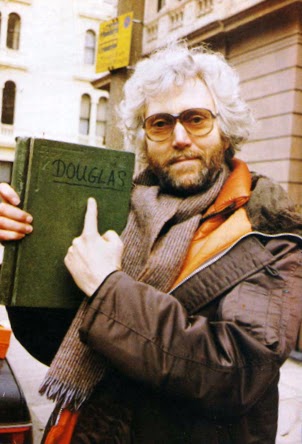

Douglas Camfield

RM. I was reading in your note that you’re a fan of Dougie Camfield. I was just remembering with my wife, the first came that he came into our house we were in the front and he said to me “So this is where you churn them out, is it?” and that wasn’t the greatest start to our friendship, but we did survive that! He did a very good job on Missing From Home, without a doubt. I thought that Judy Loe came out of it best of all, and he came out of it second best, and I think that I was probably third best. I didn’t like the ending much.

BS. Missing From Home is an interesting production in your career because, first of all, it’s a BBC production, of which there aren’t many.

RM. No, there aren’t. A producer in the BBC told me quite early on that, “The problem with you is you’re too expensive.” And I said, “Well, you’ve never even asked how much I’m on!” You know, this is agent talk. So until Missing From Home I’d never really cracked the BBC, you’re right.

BS. I only know the one episode of Survivors before then –

RM. Rubbish! Nothing to stick your chest out about. But later, I did quite a few Lovejoys for the BBC.

BS. Missing From Home was a serial rather than a series, the form for which you’d become extremely established for writing. Would that have been more difficult to get commissioned and get off the ground?

RM. It came about because Ron Craddock, the producer, actually contacted me and said “We’d love you to do something for us at the BBC. Have you got any ideas?” I said “Well, I have got an idea.” He said well tell me and I told it to him and he said, “Could you put that on three or four pieces of paper and we’ll take it from there.” And good as his word, he did. So, one of those things.

BS. What sort of form did you envisage the story taking?

RM. I envisaged it taking the form that it did, really. Six interrelated hours, like six chapters of a book.

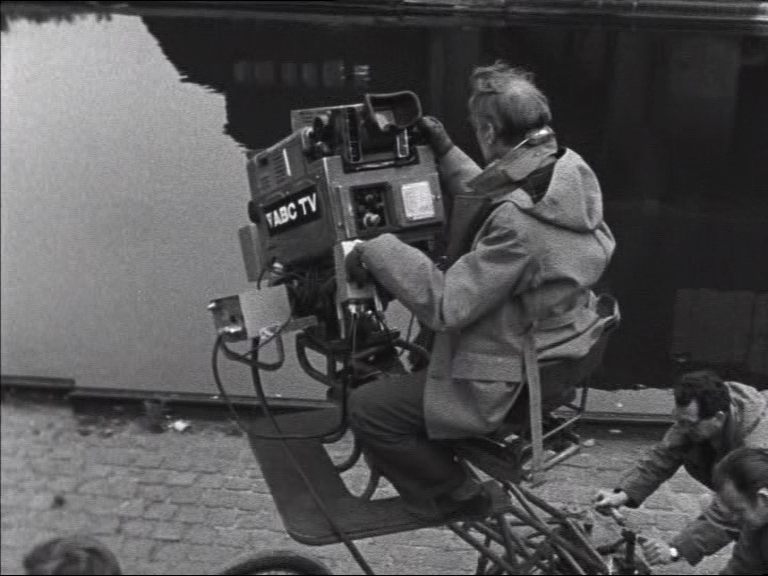

BS. One of the things that I particularly like about it is it’s a very good illustration of the merits of how television drama was made at the time; the interiors of the studio, and the exteriors on 16mm film.

RM. Yes, it was conventional old-fashioned television in that sense, with the studio and the filmed inserts. Because that’s now gone, hasn’t it? The sad thing about it was that it was very successful with the viewers and it topped the ratings – I was working in Granada when it was shown and we went to have a drink in the bar one lunchtime and somebody came up to me who I didn’t recognize and said, “Your show has just knocked the Street off the top of the charts.” I said, “Yes, its good, isn’t it?” He said, “Well, once is alright, but twice is a kneecapping” and then he turned on his heel and walked away, and I said to somebody “Who the hell was that?” and he said, “That’s Bill Podmore, he’s the overall producer of the Street” I never spoke to him again, he never spoke to me again, and that was the end of that.

But sadly, after its terrific success the show sort of disappeared; it didn’t get sold anywhere, its never been repeated. I’ve no idea why, you never know. Everybody worked on it, including the producer who was employed by the BBC would have wanted it to go on, and it didn’t happen.

BS. What do you attribute its particular success to?

RM. Well, I think that it probably worked on the level of “I’ve got to watch the next week, just to see what happens next”, on that basic level. And Judy Loe was very good in it. How did you see it? I’m interested in how anyone would get to see it today. I’d imagine that few people would have heard of it now, its just a name.

BS. I saw it for the first time recently, but I do remember my parents watching it when it was on. I didn’t see it myself because I was still at primary school, but I remember the simplicity of the title – Missing from Home – capturing my imagination.

RM. Did your parents enjoy it?

BS. Yes, they watched it for six weeks!

RM. Well, that’s good enough, isn’t it? It was a good success. There are bits of it that I remember with great affection, and I think that Dougie did it very well. I was trying to think, prior to your coming, if I’d worked with him on something else.

BS. Yes, there’s one Sweeney, ‘Bad Apple’ (Thames, 11 October 1976) –

RM. About corruption in the force. I’d forgot he did that, and I think he did a Professionals.

BS. Yes, an odd episode (‘Take Away’, LWT, 12 October 1980).

RM. The Chinese one. Yes, I thought he did that very well. It was interesting, I’d been working in Hong Kong and I was sort of gung ho on the Chinese at the time, so I sold them the idea. I got a very sweet letter from a Chinese actress in it that said it was lovely to work on something that restores my belief in British television. I don’t know who she is or where she went, but it was good.

BS. The only other thing that I’ve seen her in is Philip Martin’s Gangsters where she plays a Chinese gangster’s moll.

RM. Of course, with things like The Professionals there was no read-through where you’d meet, so we probably never came across each other.

BS. Thinking about Missing From Home, one of the points where it fits in quite interestingly with Camfield’s career is that it has a continuity with the programme that he’d directed immediately before, The Nightmare Man (BBC1, 1981), in that they both use a lot of location and are set in secluded places, but also the way in which the viewer understands the story changes throughout the run of the series. So the first episode of Missing From Home could be a thriller, when the police investigate the husband’s secret service connections, and the drama then changes to become increasingly domestic and internal.

RM. That’s true. Dougie Camfield of course worked a lot at Thames, as did I, so we came across each other quite a lot, and he lived just across the bridge in Twickenham, so we knew each other reasonably well. It was very funny, when he got the script he came over and said, “Who have you got in mind for the lead?” and I said, “Well, there’s a girl I worked with a couple of times at LWT, Judy Loe” and he said, “I don’t think I know her”. And we got Spotlight out and we saw a picture of her and he said, “I can’t make a comment but I’ll at least meet her and talk to her”. That weekend, he went up shopping in Peter Jones in Sloane Square and, lo and behold, it’s not believable, across the counter buying something for her child was Judy Loe. So he said that he did a sort of Philip Marlowe and followed her round the store, keeping an eye on all her reactions and who she spoke to, and he said, “She looks interesting. I will definitely meet her” and the rest you know.

BS. Something that’s particularly good about both her performance and the way that Camfield turns it out, which is very specific to the way that television studio drama of that period worked, is the way that she responds to rooms and is aware of space. It’s particularly striking to see the amount of time that’s devoted to showing her alone in her domestic space in that series.

RM. Yes. That was an integral part of the story. That suddenly there’s a lot of time when she is on her own, with one boy at school and another one at home, but no man around the place, and suddenly she’s got time to look around and consider.

BS. Camfield brings out a tremendous rhythm that must be there in your script, alternating between quite silent, slow, domestic scenes and her then visiting other peoples’ offices and being fobbed off.

RM. Yes. I think that’s more instinctive in the writing than considered – You don’t think ‘that will balance that’, it sort of happens.

BS. With the best directors of that period, the sense of rhythm in the script is much more apparent.

RM. Yes, well that depends upon the quality of the director. The good ones get it and those who are not so good miss it.

BS. The Suffolk locations in Missing From Home are particularly distinctive.

RM. I placed it there because it was a part of the country that I knew. We had an actress friend who had a cottage just outside Saxemunden. We took it a couple of times, so we got to know the area, and it seemed relatively unexplored in terms of television, so we honed in on that, everybody liked the idea.

That tale reminds me of a rather funny story that when we took this cottage the first time it was a very, very, hot summer and we took the kitchen table into the garden, there were a couple of apple trees, and we had our meals out there. One day we were sitting having our lunch and our son, who would have been four at the time, was sitting at the table and he had his chin literally on the table. We said “Sit up, Christopher, sit up.” He said, “I am sitting up, I haven’t got a very big chair”, they were his lines, I remember. And he hadn’t, he’d got this dinky little chair, so we changed it around and went on. A year later, we went to see an Alan Aykbourn play, Table Manners, with this vet sitting with his chin on the table. I mean this was ridiculous; it was exactly the same scene. I said to the actress who had hired us the cottage “You didn’t have Alan Aykbourn?” She said he had it the year before you did. Obviously, the same thing had happened to Alan Aykbourn as happened to us. Lovely little coincidence.

BS. With the rooms and the houses that Judy Loe visits in Missing From Home, in the end when she meets her husband’s mistress, there’s a very immediate and intricate sense for the viewer of this being a different space, in the way that all of the mistresses’ furnishings reflect the way that she lives her life. Do you think that this was something that worked particularly well in studio drama?

RM. I can’t remember that, it’s been a long time since I saw it. I imagine that it would have been something that Dougie had done very deliberately, to have visually set up what was happening in the relationship. I didn’t even remember that one saw the husband’s mistress.

BS. The casting of it is also interesting in that Camfield used a kind of repertory company, so there are people like Jonathan Newth in it –

RM. Well, he was the man that she met when she went to the school. He was a father. I thought that those scenes together worked very well, I thought he was excellent.

BS. There’s a counterpoint to the interior, studio, scenes in the way that Judy Loe responds to the Suffolk countryside and locations like the railway station and canals. Do you have a kind of geographical sense when you’re writing of the topography of where things are set and how the viewers come to understand them?

RM. Well, it was particularly appropriate in the shows that I did at Granada, the two big ones where I wrote all of them [Travelling Man and Floodtide]. Because they were such a long stint of work, four years or something, I got to know all the Production Managers, and got to a sort of wonderful thing that you can’t really achieve in television very often when I would be able to say to them, “Look, give me a location and then take me to it and show it to me, and then I’ll write the script about what you’ve shown me” and they said that’s fabulous, because it suddenly brings them into the forefront of the production, and it worked terribly well on both of those series. And then in Floodtide I went with them to France and it paid off again. Not easy to do – I mean it was easy for John Ford to go up to Monument Valley and the rest of Hollywood will wait. Television doesn’t work that way. Not often, but it did on these two occasions.

BS. I’ve read that both of those series were shot on Outside Broadcast on single camera. So when you initially went to the locations were you recording them on a camcorder?

RM. Oh no, I just went with a pad. They’d say, “Well there’s that farm over there, and if you’d get… I think that it might be good, and you could see the hill behind and the train.” So it was evolving, and it just required me to move the pieces around in the front, which was great fun.

The two series that I made for Granada were interesting in your relation to the theory of space. They’re both heavily full of location, but the locations came before the story which was a lovely, luxurious way to work in that you were writing a scene for a place that you know exists and you can visualize it. It was just lovely. It gave the whole show a lift – particularly when you’re walking around Harfleur on the French coast and you see the fisherman with their nets and you think, ‘Oh God, this is all there, isn’t it? I don’t have to do anything!’ Lovely, a great privilege.

BS. Single camera was very much a different discipline to film or studio. Did you approach that warily?

RM. No, I didn’t. I left that to them. I’m not sure that many directors want too much in the way of camera instruction, and I certainly didn’t give it to them. But then, of course, in this particular instance one guy was directing them all as I was writing them all, so we had a sort of shorthand, where he would say “I’m not happy about… I think we could…” etc, that give and take.

BS. Something that I’m very interested in historically is the relationship between the writer and the director. In the series that you initially worked in the sixties and seventies, were you aware of whom the director was going to be, or be likely to be?

RM. Well just occasionally you had a director who brought so much more to it than you imagined that anyone could do, that you immediately thought “He’s somebody I’d like to work with again” and I sort of evolved the idea that the writer-director relationship was a great element so – you mentioned Public Eye. Well, the original director of that, Kim Mills, stayed with it all the way through, of course, and we had a very profitable relationship.

BS. Because he produced the Brighton series as well –

RM. As well as directing three of that series. That was just marvelous.

BS. It’s interesting that you talk about this close relationship between the writer and the director with Public Eye, Travelling Man and Floodtide – it being both a preferable state of affairs, but also quite a rare one.

RM. Yes it is, I don’t know why it should be that rare. But the most successful things that I have ever been associated with, The Avengers or whatever, have been with a small handful of particularly good directors.

Dougie was never very strong. He had a bad heart, which killed him in the end

BS. You were fortunate to get his work right at the end. Missing from Home was shown posthumously.

RM. Oh God, that’s terrible. Another strange thing is that Judy Loe was absolutely rock solid – super performance all the way through – and the next year nobody wanted her, because she was a star now, so they thought they couldn’t afford her. And the next thing that she did was a part in Travelling Man. That was the first time that she’d worked since. She knew Leigh Lawson quite well, so it was marvelous to see her working.

BS. She’d recently been widowed when she made Missing from Home.

RM. Yes, Richard Beckinsdale. We watched an episode of Porridge at Christmas. He was so good, such a tragedy. She’s married now to a director, ex-BBC.

BS. In comparison with contemporary television drama, it’s interesting that you could have such a successful series that wasn’t predicated or marketed around any star casting.

RM. No, but then you can be very badly served by your masters. I did a series for LWT with John Thaw called Mitch (LWT, 1984) and we started with a series of thirteen and then we were cut down to ten because they were in some sort of financial difficulty. And then because of this mythical financial difficulty we were on the shelf for eighteen months, so by the time that the opener, which was about policing the streets of Brixton, was transmitted it was about as topical as Victoria’s Coronation. We never got any publicity although we had the hottest actor in British television playing the lead. But it was a good idea, well done with no reward at all. Very disappointing. That happens.