(Review of Red Letter Day: The Complete Series, originally published on Tachyon TV, 2011)

Thanks to the canonical status of the BBC’s Wednesday Play and Play for Today, people have a selective memory when it comes to the single play. We tend to remember two particular types of drama whenever the form is mentioned as something now gone that British Television used to do; the Ken Loach–Tony Garnett Cathy Come Home/ Up the Junction mode – filmic, directly socially engaged with a documentary feel – or the Dennis Potter–David Mercer Brimstone and Treacle/ Let’s Murder Vivaldi model – intensely concentrated and realized in a consciously experimental and stylized form with strong affinities to the stage play.

This only tells some of the story, as the version of the single play which most viewers experienced most often was in series such as Red Letter Day – on ITV rather than the BBC, 50 minutes long rather than 75, and only infrequently overtly political in content or experimental in form (although Red Letter Day does include examples of both these approaches). This DVD release follows on from Network’s two superb recent collections of 1970s Armchair Theatre plays from Thames, and gives viewers a further chance to see more popular ITV single plays in this mode.

Made by Granada and transmitted in 1976, Red Letter Day was an anthology series based around the easy-to-follow premise that each play would follow a day of unusual significance and consequence for its protagonists. The series was originated and script edited by Jack Rosenthal, who wrote two of the plays and supported the development of the other five. Rosenthal’s own status as leading television playwright gave him particular sympathy into the idiosyncrasies and concerns of other writers, resulting in a series of consistently high quality and intelligence, marked by the widest range of styles and authorial preoccupations imaginable. Any viewer who especially enjoyed one play in Red Letter Day who tuned in the next week expecting something similar would be likely to be disappointed.

Until now, Red Letter Day has been best remembered for only one production, Rosenthal’s ‘Ready When You Are, Mr. McGill’, repeated by Channel 4 in the eighties, remade by ITV thirty years later, and already commercially available. Much loved by people who worked in television at the time, Mike Newell’s film shows a day in the life of Joe McGill, an extra given a small but vital line in a television play being shot on location, a chance that he blows after being left waiting, ignored and patronized on set all day. Much of the pathos and conviction of this production come through the casting of a real-life extra, Joe Black, as Mr. McGill. Because the unfamiliarity of the lead really does convey obscurity to the viewer, the inappropriateness of McGill’s fellow feeling towards the experienced TV professionals and the sadness of his failure feel uncomfortably convincing. McGill’s position is shown in parallel to the misfortunes and anomie faced by the (fictional) play’s director, a terrific performance by the youngish Jack Shepherd. The film builds towards a memorable confrontation between these two characters and their viewpoints after McGill’s hapless delivery of his line,:

McGill (exploding): This isn’t real life, lad! It’s pretend! It’s all pretend! You’re pretending! The whole damn-fool film’s pretending!

Director: Real life is how well we pretend, isn’t it, sir? You, me. Everybody in the world.

It must be said that once you’ve seen a few of Rosenthal’s single plays you tend to know how they’re going to work. You’ll be shown how a certain profession works – a taxi driver learning the knowledge, a football referee, an electoral register – and through the vicissitudes faced by one character a wider view of how the world operates and the value and function of the individual within the system will be presented. The familiarity of this form is unproblematic in a great play like ‘Ready When You Are, Mr. McGill’, but in lesser material such as Rosenthal’s other Red Letter Day, ‘Well Thank You, Tuesday’ his approach can become more cozy than surprising. This drama shows a registry office at work, following the three parties who arrive to register one individual birth, marriage and death through their day. As with a lot of dramas with several interlaced stories, ‘Well Thank You, Thursday’ suffers from some being less interesting than others. If you’re old enough to remember the mid-1970s, subsidiary interest is maintained by the attention to detail paid to the various domestic interiors realized in the Granada studios. Watching this with a colleague, we both found ourselves continually distracted by thoughts like, “My mother used to have a hairdryer like that” or “I’d forgotten that domestic homes used to have those heavy telephones mounted on the wall”

‘The Five Pound Orange’ of Donald Churchill’s play isn’t a fruit, but a priceless Victorian stamp, around which the plot revolves. If you’ve seen Churchill’s contemporaneous Armchair Theatre plays on the recent Network collections then you’ll have a strong sense of what you can expect from this author; farcical stories in which quirks of fate throw a nervy and disappointed middle-aged man into the arms of a woman. ‘The Five Pound Orange’ is more in the same vein, but with the major advantage that there was never an actor better at conveying nervous and disappointed middle-age than Peter Barkworth. The material Barkworth has to deal with here is hardly Telford’s Change or Manhunt – and he faces the considerable handicap of wearing a costume that includes a pair of green tartan trousers – but he still manages to derive a lot of poignancy and empathy out of Churchill’s rather chauvinist light comedy, when seen alone stroking a cat and sighing in a darkened room or hiding in a wardrobe while being cuckolded by Bernard Horsfall.

Willis Hall’s ‘Matchfit’ is the only play in the series to derive from another source, one of Brian Glanville’s football stories for boys that were familiar to schoolchildren between the sixties and the eighties. This literary origin makes this edition feel more like a short story than a play or a film, told retrospectively in voice-over. A tale of a boy placed in a hospital room alongside an archetypally dour Glaswegian football manager, it’s not a play that holds much in the way of surprises, but touchingly realized by Roddy Macmillan as the coach and Steven ‘Tarrant in Blake’s 7’ Pacey as the young man.

Neville Smith’s ‘Bag of Yeast’ is based around a premise that you might expect to be light and comic – a young working-class Liverpudlian decides to become a Catholic priest – but is quite relentlessly glum, showing the consequences of this decision as a sequence of betrayals (of his father’s socialist humanism) and separations (from his family and fiancée). The style of this film is a flat, slow realism, recording key scenes in continuous takes and refusing to cut once confrontations have reached their climax, leaving the viewer watching sights like Alison Steadman (as the rejected fiancée) in tears, or the overturned glasses on an empty pub table after the father has hit his son, for an uncomfortably long time. The lack of any palliative catharsis that this play offers makes it a pretty grueling watch.

C. P. Taylor’s ‘For Services to Myself’ pivots around a teacher and community activist deciding whether or not to accept an OBE. Like ‘Bag of Yeast’, this film asks to what extent accepting public recognition requires compromising one’s principles, but – while it doesn’t shy away from showing the difficulty of the decision – is less overtly pessimistic. The play has a dual time scheme, showing an unsmiling and uncertain Roger (Alan Dobie) waiting in London hotel rooms and Regent’s Park working out if he should go to the palace to accept the ennoblement, interlayered with earlier scenes of him at work and with his family in the North East. The dilemmas faced by Roger in these scenes – facing the disapproval of his far-left brother, being looked over as head of department in favour of a younger and more conventional teacher, seeing his children struggle to support his granddaughters – make his impassive responses to his familywhen he gets to London more sympathetic, and give the play considerable subtlety and depth. The way that the play signifies the transition between the two streams is striking and effective, freezing the last frame of one scene for a moment before moving on to the next. Although the location filming of ‘For Services to Myself’ locates it directly in the specific world of 1975, this play felt the most contemporary of the series in its concerns to me.

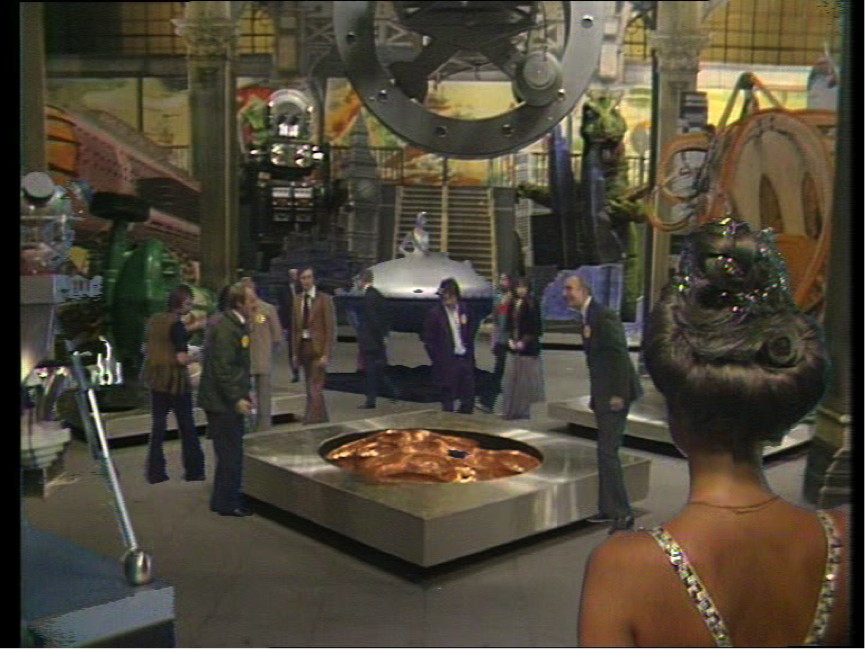

Howard (Rock Follies) Schuman’s wildly non-naturalistic ‘Amazing Stories’ is very much the joker in the Red Letter Day pack, reviewed in The Stage under the memorable headline ‘Sometimes there’s such a thing as television drama that’s too original’. When Schuman’s off-the–wall script arrived at Granada, producer Michael Dunlop wanted to drop the production and had to be compelled by Rosenthal and Head of Drama Peter Eckersley, to continue with the production. The play revolves around two separate red-letter days – in the world of the television studio, friends Stanley and Eddie (Joe Melia and John Normington) attend a science fiction convention to meet their hero author E. B. Fern, while a concurrent black-and-white narrative – a story dreamed up by Stanley – is realized as an Invasion of the Bodysnatchchers-type film within a play, in which fictionalized versions of his family are transformed into carrots. Stanley hopes to escape from his own unsatisfactory family life through gaining the approval of Fern, but the creator of amazing stories has his own real-life troubles to escape from.

Apart from the cinematic pastiche, ‘Amazing Stories’ is filled with a dizzying amount of spectacular images and incidents. The mundaneness and enervation of Stanley’s domestic life is realized in absurd terms, dad, wife and mum as a gloomy chorus in a grey and threadbare room while he dances around them. This is contrasted with the tremendous visual flair with which the sci-fi convention is realized, a TV studio aesthetic somewhere between pop art and fringe theatre, using a lot of CSO to create an elaborate and fantastical world out of nothing.

There are an awful lot of extraordinary things to look at in this production; King Kong, wolfhounds, a dematerializing TARDIS… and – most strikingly of all – Rula Lenska in a silver lame bathing suit as Ms. Fandom and Ian McDiarmid as the supercool Blade (“I think you could get very excited about apathy”), whose shades, leathers and bleach-blonde image is a doppelganger for Lou Reed circa Sally Can’t Dance.

All of this originality and imagination certainly runs the risk of overpowering the viewer, and that it manages not to is a tribute to Joe Melia’s performance as Stanley, which always manages to remain rooted in an emotional reality, whatever bizarre circumstances he finds himself in. Melia was Schuman’s first choice for the role “I couldn’t think of anyone who could do that energy masking deep despair better than Joe”

Although some are of greater interest than others, every play on Red Letter Day is rewarding to watch and has its moments of emotional engagement for the viewer beyond historical curiosity. ‘Ready When You Are, Mr. McGill’ fully deserves its canonical reputation as a masterpiece, and in their very different ways, both the C. P. Taylor and Howard Schuman plays are extraordinary. One is left wondering what other of these two writers’ plays are still gathering dust in the archives, and if we can ever get to see them again, please. Red Letter Day is a fitting tribute to Jack Rosenthal as both a writer and as an editor who had the confidence to see the potential in other writers’ work, encourage them and to let them follow their own individual instincts, creating a series of tremendous diversity and value.