(Text of a paper given by Billy Smart at ‘Television for Women’, University of Warwick, 17 May 2013)

What I’m going to do today is present a long-forgotten drama of some significance to you and – through close textual analysis of it – demonstrate how the spatial conventions of studio television drama could be used to present women’s experience to viewers, realised through visual codes – of performance, physicality and aesthetic detail – as much as through verbal means. By ‘studio drama’, I mean drama that was made on videotape in a multi-camera television studio, the dominant form of television drama in Britain up to the 1980s.

I’m very excited about the programme that I’m going to discuss today, because its not very often that you can say that you’ve uncovered a major work, but Patricia Hooker’s 1973 Armchair Theatre play, ‘The Golden Road’ really is one. It’s a work of major historical significance because – even if it perhaps wasn’t the first lesbian play for British Television – it must surely be the first one written by a woman. But more than that, it’s also quite terrifically good, and no one – save for Leah Panos and myself – has seen it for forty years!

The play has a simple Aristotelian rise-and-fall narrative. A young woman, Anna (Katy Manning), arrives unexpectedly at the door of mother and housewife Cass (Olive McFarland) and becomes her lodger. The exotic Anna has a transformative effect on Cass’ life, awakening dormant aesthetic and sensual perceptions to change the way that she comprehends the world and sees herself: “Not Mrs. Hunter, not mummy. Cass!” Anna and Cass sleep together. The husband, Jim (Neville Barber), realises what’s going on and goes back to his mother (Joyce Heron), taking the daughter, Christie, with him. Jim denies Cass any access to Christie (Karen Corti), and Cass realises that to have any possibility of keeping her daughter she must cease contact with Anna. The play ends with Anna locked out of the house.

Lesbians were rarely seen in 1970s British television drama. I’ve only found four single plays with lesbian themes (Armchair Theatre: Wednesday’s Child, ITV, Thames, 1970; Armchair Theatre: The Golden Road, ITV, Thames, 1973; Second City Firsts: Girl, BBC2, 1974; Play for Today: The Other Woman, BBC1, 1976), plus a handful of subsidiary plots in episodes of legal, police and medical series. The inclusion of lesbian characters generally served one of two dramatic purposes; either a device for partial and withheld character information – so half way through an episode the viewer would think, “Oh, of course, I see, so that explains the hold that she had over her!” – or, more problematically, as a psychological or social “issue” to be explored. The nadir of the “issue” approach is perhaps an episode (‘For Life’, 1975) of the women’s prison drama Within These Walls (ITV, LWT, 1974-78) that ends up being about the heroic tolerance of the prison chaplain, rather than the prisoners he ministers to. This episode makes more sense to a present-day viewer once you learn that the actor who played the chaplain (David Butler) also wrote the script.

‘The Golden Road’ combines elements of both approaches. Cass doesn’t realise Anna’s sexuality or understand the nature of their attraction until the end of Part One, and after Cass loses custody of her daughter ‘The Golden Road’, of necessity, has to become an ‘issues’ play, once Cass’s legal status as mother becomes dependent upon her sexual identity.

So who was the mysterious Pat Hooker? It took me two years to find out anything about her. Before the Internet, you could have a writing career and leave no trace at all of your personal identity for posterity. Initially all that I had to go on were a dozen or so television credits between 1971 and 1981; three plays and assorted episodes of legal, police and medical series. She also had a play, A Season in Hell, on at Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre in 1967 and went on to adapt various science fiction classics for BBC Radio in the 1980s (The Death of Grass from John Christopher, 1986; Fear on Four: Survival, from John Wyndham, 1989).

Eventually, I discovered one 350-word newspaper interview, from which I found out a few pertinent facts. She was Australian! She was born in Balgowlah, Sydney, in 1934 and made a name for herself in Australian television and theatre with a play about Rimbauld and Verlaine. In order to further her writing career she moved to London in 1964, supporting herself by working as a court reporter.

But that was all that I could find out, save for a minimal entry in the Oxford Companion to Australian Literature detailing her stage plays, which seem to have concentrated on the mythical, the biblical, the ancient and the poetic:

Hooker, Patricia was at one time employed in the ABC programme department; she left Australia in the late 1960s to write in London. Her plays include A Season in Hell (1965), which re-creates the personal relationship between the poets Rimbaud and Verlaine; Socrates, where the force of truth is ranged against that of malevolence; Concord of Sweet Sounds, a study of an ageing concert pianist; Twilight of a Hero, about the biblical father-son pair, David and Absalom; and The Lotus Eaters (1968). (Oxford Companion to Australian Literature, 1994)

From this thin set of resources, I’ve come up with the theory that Hooker’s dramatic style distinctively combined a mythical-poetic understanding with her court reporter’s eye for everyday detail. This dichotomy lies at the heart of the drama of ‘The Golden Road’ where Anna is a mythic figure with the power to bring an awakened poetic sensibility, placed in the quotidian location of a suburban household.

The disturbing effect that Anna has upon the quotidian world is made immediately apparent in her introduction in the first scene, when she appears, not at the front door, but an upstairs bedroom –

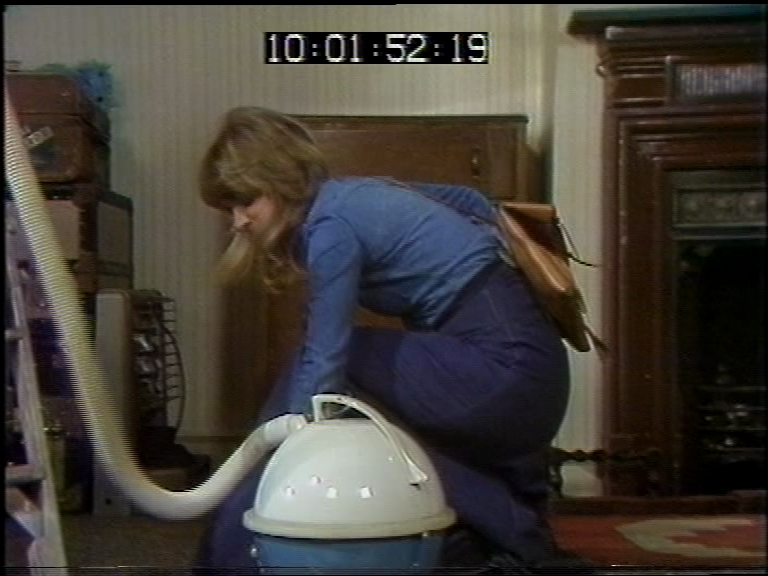

– disrupting Cass’s everyday domestic household procedure of cleaning –

– meaning that Anna’s very first action in the play is to turn off a vacuum cleaner, an understated, but highly symbolic action.

Note how these three frames are arranged: The arrival of Anna is immediate and not prefigured, Cass is placed in a physically awkward position on the other side of the room stood on a chair, and Anna physically imposes herself on the space. The disruptive effect implied in the script is fully realised through directorial decisions of composition and framing.

Which brings me to the second figure instrumental to the success of ‘The Golden Road’, director Douglas Camfield. Unlike Pat Hooker, much is known about Camfield, who is best remembered for his work on Doctor Who (BBC1, 1963-89) and The Sweeney (ITV, Thames, 1975-78). ‘The Golden Road’ isn’t the type of drama that he is best known for directing, and indeed he was only assigned to the play late on, when the intended director, Darrol Blake, fell out with Armchair Theatre’s producer, Joan Kemp-Welch.

Hooker’s script would always have been interesting whoever directed it, but having Camfield in charge was a stroke of unexpected good fortune. Because the one central quality of his direction, found throughout his work, lies in an acute sense of the dramatic possibilities of space. This makes ‘The Golden Road’ a happy instance where all of the nuances and implications in the writer’s script were realised with clarity and imagination through the ideas of the director, as I will go on to demonstrate.

Camfield’s direction always achieves movement, in the studio as much as on film. Two simple things immediately set his studio work apart from his peers – mobility of the frame and depth of field. A simple description of what made Camfield’s direction distinctive is that it makes the use of the camera and editing act like a narrative voice. Unlike most television direction of his time, his productions seem familiar with the idea of moving the TV frame around in order constantly to refocus the viewer’s attention or delay revealing an important development until the best possible moment. I’m going to play you a whole scene from ‘The Golden Road’ – Cass introducing Anna to her mother-in-law, to demonstrate Camfield’s studio sense in action: bringing out the rhythm of the scene through framing and shot selection that makes underlying attractions and conflicts explicit, and tells us something of how much each character understands the situation. (clip)

Several things are worth observing here. On paper, the scene is potentially rather static – four people eating dinner talking about their lives – with action contained in the inferences of the dialogue. After a teasing, and thematically astute introduction with a close-up of unfamiliar exotic food, Camfield brings out these inferences through close-up observation of individual responses, giving the viewer a precise and detailed sense of individual character; Anna provokes, Cass is naively enthusiastic, mother forbids, Jim spectates. It isn’t until three minutes into the scene that we get a prolonged shot of all four characters together. The scene also achieves mobility in how it places Anna within the frame, in charge of the evening, moving to and from the table. This arrangement is implicit in Hooker’s script, but Camfield accentuates it by, throughout the scene, only moving the camera in shots where Anna is doing things; the character with the catalysing power to affect and change situations. It is important to remember that this scene, consisting of 44 shots in four minutes, would have been shot in one take, with mixing between cameras done live at the moment of performance, giving the viewer a real sense of spontaneous reaction.

Camfield’s close directorial style enhances Hooker’s more symbolist and poetic scenes as much as it does to her relatively straightforward domestic ones. This is particularly apparent in the play’s most overly allegorical scene, in which the two women discuss the Golden Road to Samarkand and the fate of the daughters of the Philistines in the book of David while Anna rubs ointment into Cass’s face. Camfield concentrates on the action of the anointing, the sharply-defined 2” videotape image picking out exotic details of Anna’s braided dress, jewellery and nails.

Camfield’s shots emphasise the strange and otherworldly aspects of the women’s situation, with Cass seen upside down from Anna’s point of view –

– and, eventually, blinded to the outside world.

Unusually for this time and medium, Camfield’s treatment of the scene uses point of view shots continually, and with precision.

The effect is like a novel, with insights into both women’s understanding of the situation allowing the allegorical discussion time – and space – to take root in the viewer’s imagination. This makes a scene that might otherwise be rather silly seem surprising, even spellbinding.

The viewer has become Cass, with no option but to lie back, listen to the strange stories and allow Anna to rub our face.

A frequent Camfield technique is to add mystery and surprise to the viewer’s spatial understanding by starting a scene on a detail of a space, and letting the viewer work out its place in the room that will eventually be revealed. ‘The Golden Road’ does this frequently, emphasising the potential strangeness in the everyday domestic –

– and reflecting the changed situation of characters, understanding familiar places from a new, perhaps frightening, perspective.

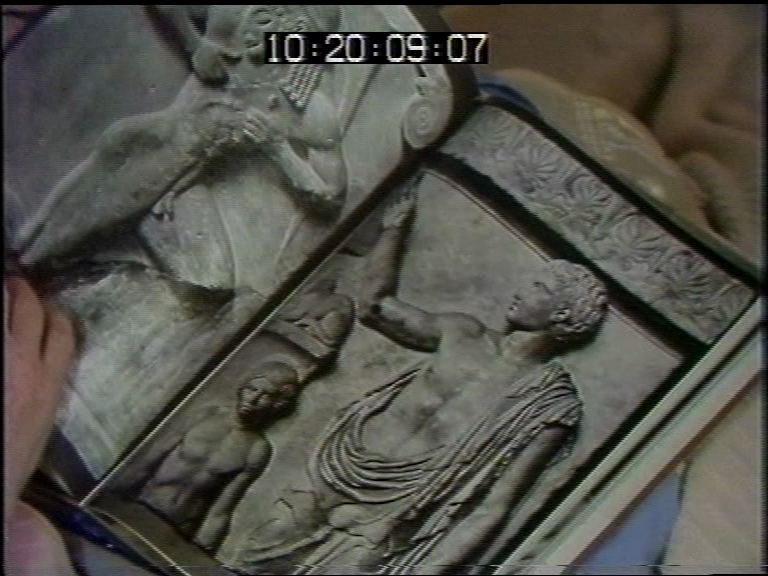

This bold close-up attention to detail make the viewer of ‘The Golden Road’ share Cass’s experience of the unusual new stimuli that Anna has introduced her to, such as exotic cooking –

– and an interest in mythology.

This reversal of the viewers normal spatial expectation of how information is conveyed – giving the detail before the establishing shot – is frequently used to introduce Anna unheralded into a scene that has already started, cutting into a close-up –

– before establishing her relationship to the space of the room.

– emphasising her disruptive nature as an initially mischievous – and eventually tragic – figure.

Anna is often presented within the frame as an active character, engaged in activities that just slightly push against expectations of decorum within the environment depicted, such as drinking beer at the table –

– or smoking in bed.

This activity sometimes takes the form of actively physically imposing herself on the situation, here bumping against Jim as she goes into the bathroom dressed in only her underwear –

Or, in one of the play’s final scenes, vigorously intruding into the mother-in-law’s home.

Sometimes this motif of Anna’s physical assertion into the space doesn’t even need Anna’s corporeal presence, felt in her place through the introduction of alien exotic details into the home, such as this coffee percolator.

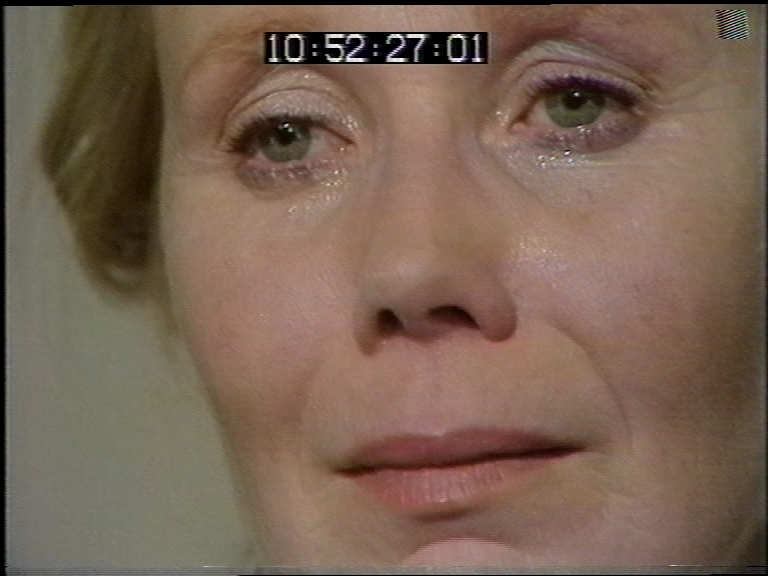

By contrast, Cass is presented within the frame as a reactive figure, rather than an assertive one. Unlike Anna, her self-understanding is presented through moments of literal self-reflection. Her developing understanding of the constraints of her marriage –

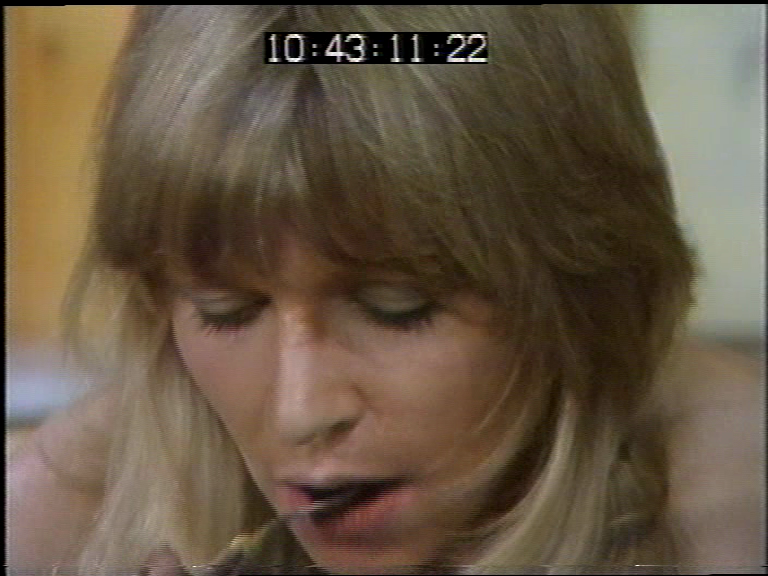

– is itself mirrored at the post-coital apex of her journey within the play, a moment of epiphany that is immediately followed by a swift fall.

Close-ups of Cass show her reacting to situations, rather than instigating them. Unlike Anna, Cass’s expressions are always easy to emotionally read. When seen at such close range, these displays of Cass’s feelings, so emotionally unguarded as to be rather childlike, work as staging posts in the rise-and-fall tragic narrative of ‘The Golden Road’.

As seen in the uncomfortable final shot of the play.

Much of the narrative power of ‘The Golden Road’ is achieved through associative visual logic, with each moment reflecting other moments in the play. So, the play’s last scene acts as a mirror of the first, with Anna again an unexpected apparition at the door –

– and Cass again interrupted while performing housework, but this time she is packing up Anna’s things –

– with Anna now unable to impose herself on the scene, instead leaving the room, a literal moment of closure.

So, to conclude, ‘The Golden Road’ subverts its domestic mise-en-scene to present a coded representation of different female experience. The domestic space is reconstituted through the physical presence and aesthetic sense of the women within it, realized through exotic, ‘other’, details of costume, décor and food. This rich, allusive and associative drama was fully realised through the intimate, watchful and spontaneous conditions of studio drama.

A companion piece to this article – ‘Looking for Pat Hooker: The Invisible Writer’ by Billy Smart – can be read here.

Here’s a fifth single play with a lesbian theme that went out in the 1970s. ‘Connie’ was written by the poet and playwright Derrick Buttress and was directed by Derek Lister. The name character was played by the superb Marjorie Yates; also in the cast were Ray Mort, Gwen Nelson and Janine Duvitski. The play went out on April 27th 1979 in the series of plays made at Pebble Mill for BBC2 under the title ‘The Other Side’. I know because I was the producer.

Pingback: Armchair Theatre: The Golden Road (ITV/ Thames, 30 October 1973) | Forgotten Television Drama

Pingback: Angels: Series 2 (BBC1 1976) – Viewing Notes | Forgotten Television Drama

Is this available for viewing and/or purchase anywhere? I know a lot of Doctor Who fans who would be very interested.

Thanks for your comment, Gabriela. “The Golden Road” is not publicly available but there is a copy held in the National Film and TV Archive at the British Film Institute, London.

I have been trying to identify a play I saw back late 1973, early 1974 which had a lesbian theme and from what I remember it is not any of those mentioned here.

It was on ITV (I was in Wales at the time so not sure who produced it) and for some reason we ended up watching it instead of Monty Python.

The basic plot was that a young couple living in suburbia are visited by a female friend (no memory of her connection to them) who seduces the wife, but in the end the wife goes back to the husband. I say it’s none of plays listed as one thing I clearly remember is that the seductress was ‘older’ than the couple (probably late thirties or older) with shortish smooth dark hair (well, we saw in in b&w, and a picture of Prunella Ransome in Wednesday’s Child does not match my memory of the actress – was that play repeated at the time I am thinking of?) and carried an air of sophistication compared to the couple.

The identity of the play has been bugging me for years and questions on TV forums have failed to help. I am wondering it was a live production wiped afterwards .