Inclusive design is a now well-established part of the second year BA Graphic Communication curriculum. We’re proud of how we’ve continued to evolve how we embed inclusive design in the degree since our early Breaking down Barriers team initiatives in 2015 and the impact this has had on both students’ design practice and their research. This academic year, Jeanne-Louise Moys and Rachel Warner invited two recent alumni to share their experience of learning about inclusive design and its relevance to their careers with our current Part 2 cohort.

Laura Marshall (class of 2019) and Eden Sinclair (class of 2020) both chose dissertation topics related to inclusive design during their BA Graphic Communication studies. Coincidentally, they both now work as Visual Designers for IBM.

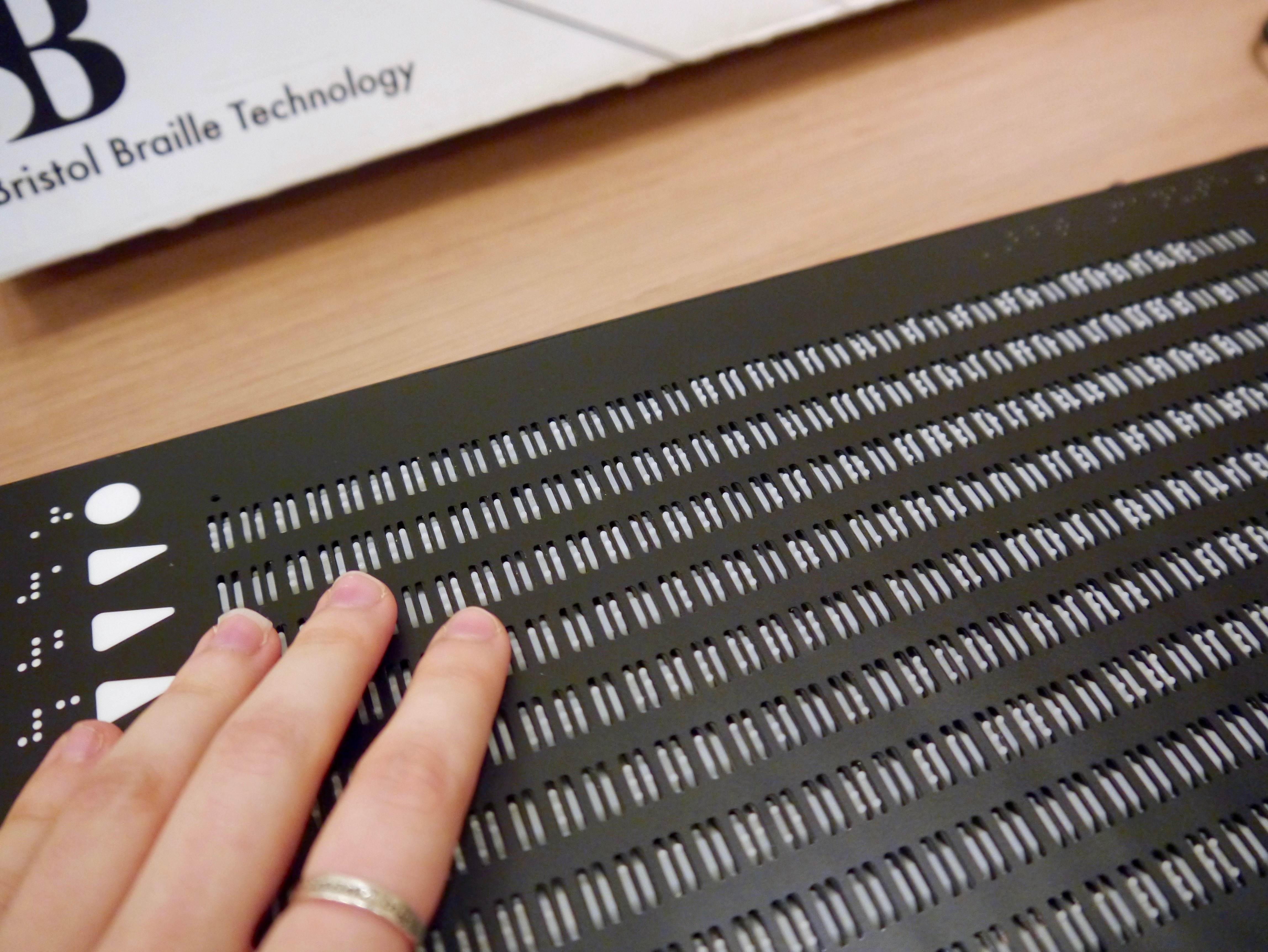

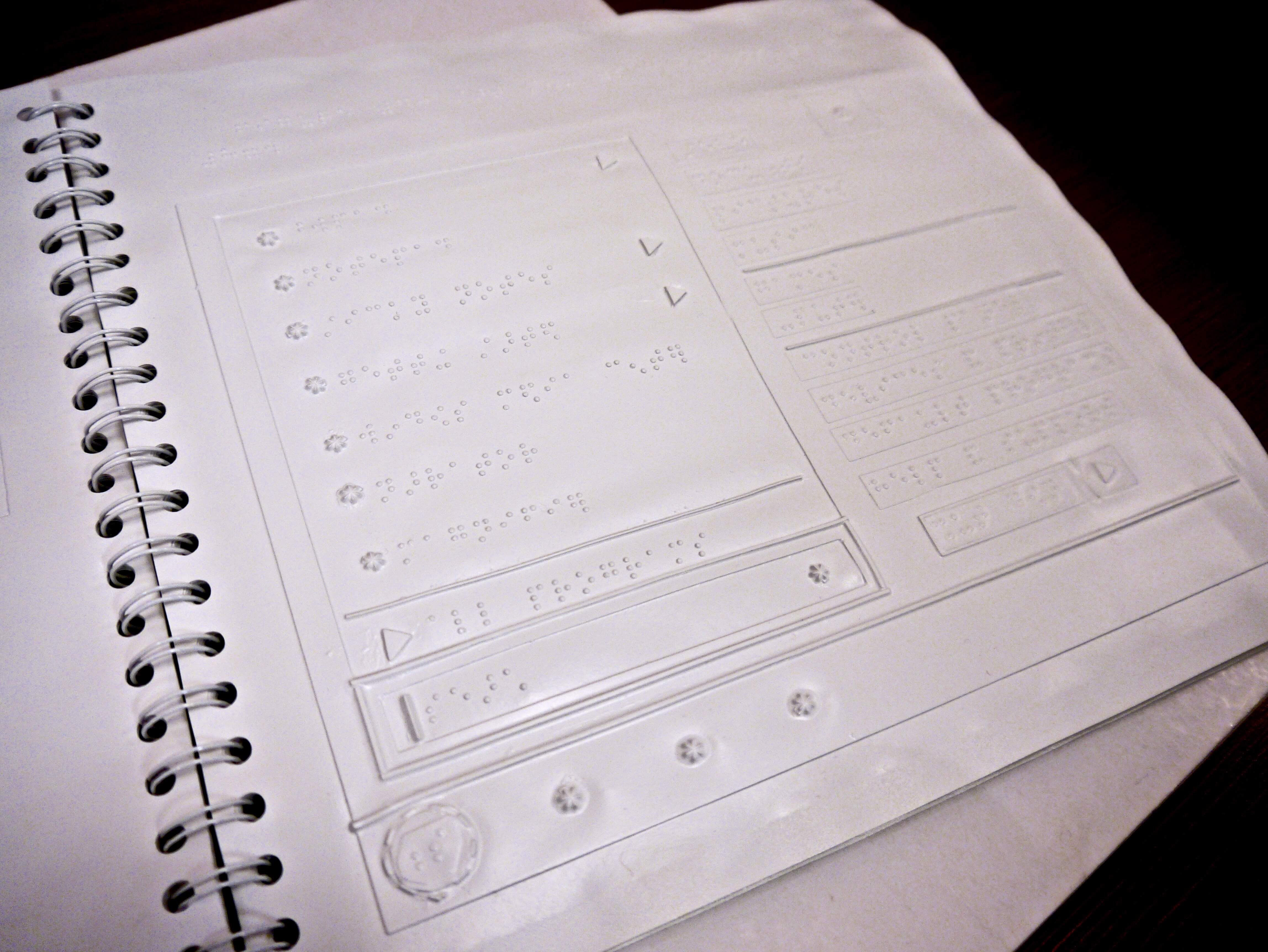

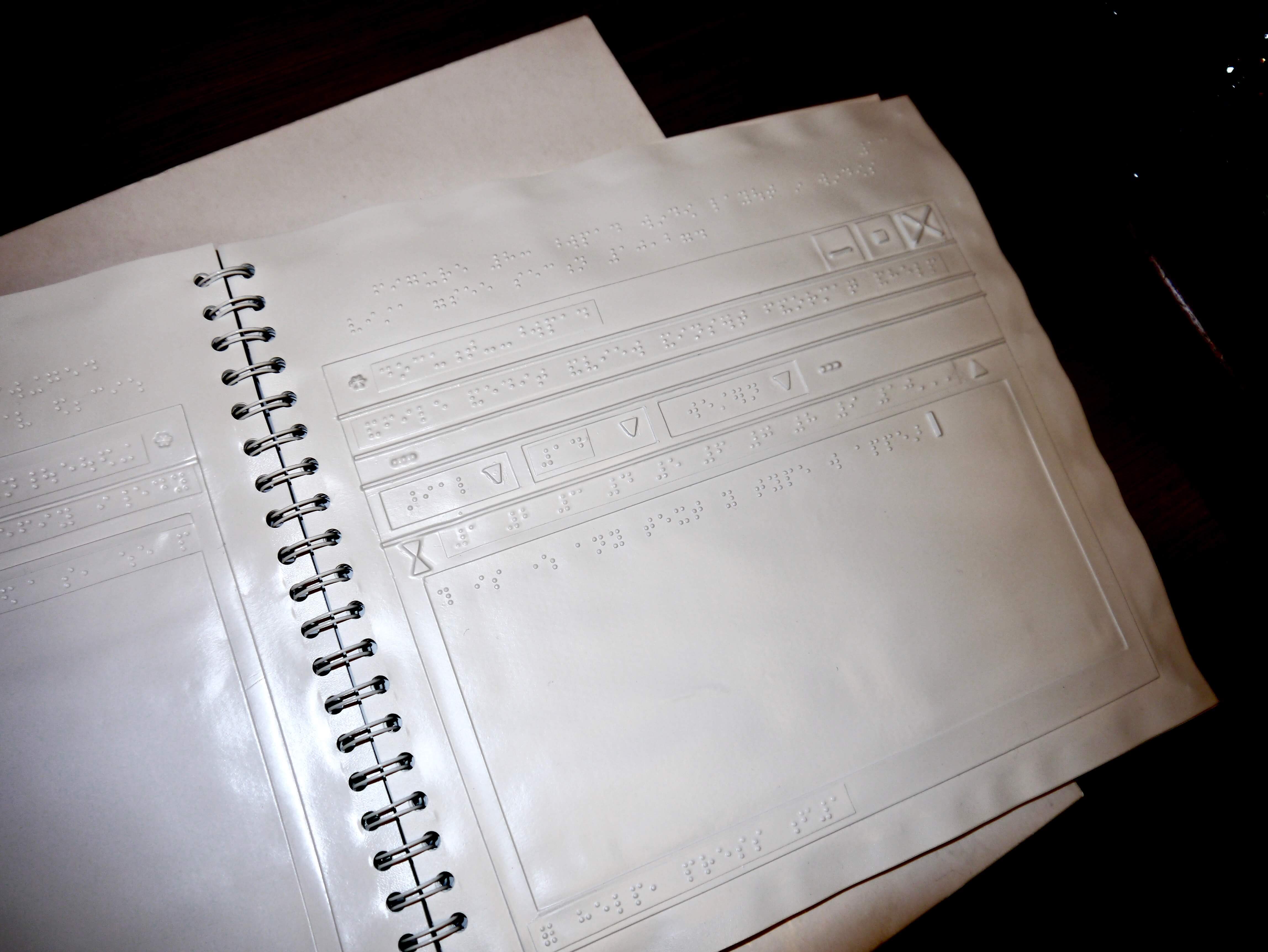

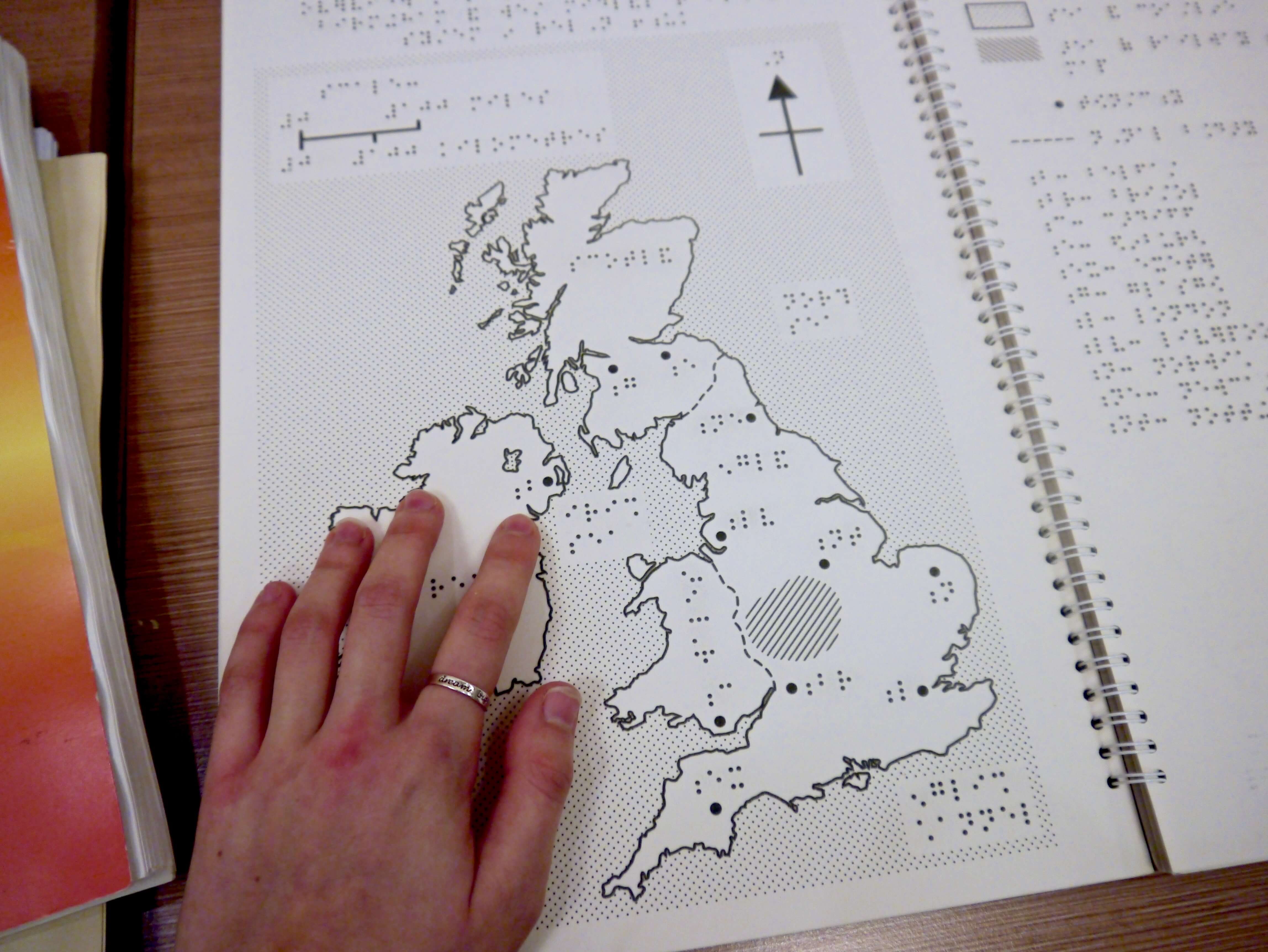

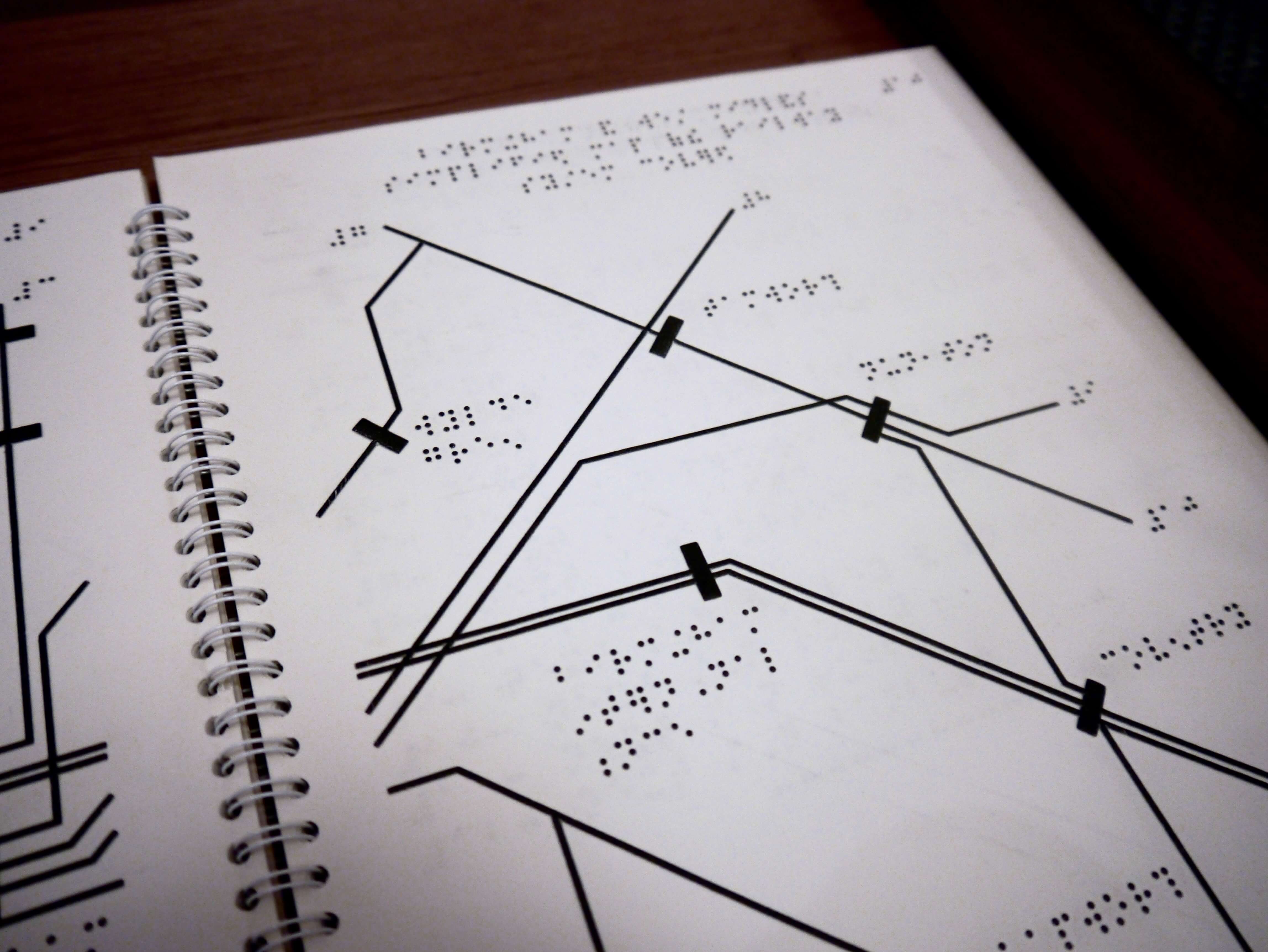

Laura’s dissertation explored the role of braille and digital assistive technologies for people with visual impairments. She collaborated with the Reading Braillists and conducted surveys and interviews to understand the varied reading needs and experiences of the blind community. Her research has subsequently been published in Visible Language.

Laura says: “Choosing to do a dissertation focusing on inclusive design allowed me to start thinking about designing from a different perspective. Of course, as designers, we understand the fundamentals of accessible design: legibility, text size, colour contrast etc. but it wasn’t until I met and talked to individuals with visual impairments could I truly understand the impact and importance accessible design in their everyday lives. As big and scary as a dissertation seemed, it is probably the piece of work I’m most proud of from my time at Reading, as well as the piece that has impacted me most in my career, so would greatly encourage exploring an area of accessibility you know next to nothing about to change the way you think when you design something new.”

Eden’s dissertation evaluated considerations for user interface design for people with neurodivergence. She looked at visual overload and how motion, brightness and visual metaphor might affect a user’s anxiety and overall experience. She conducted a series of participant studies to explore the impact of different conditions on user experience for people with Autism Spectrum Disorder and neurotypical users. Her findings helped her identify relevant recommendations for inclusive user interface design.

Eden says: “I’m so glad that I has the opportunity to explore inclusivity through my research at Reading, as inclusive design is a part of everything that I do and informs every design that I create.”

Laura and Eden prepared short, engaging video presentations which we shared with our current Part 2s as online resources. They explained their interests in inclusive design, how they carried out their research and how it has informed their own practice.

These graduate talks were provided as part of Part 2 Guided Independent Study (GIS), to prepare for a workshop about applying inclusive design guidelines and advice into design practice. A reading list was provided that included literature introducing students to guidelines such as those from the RNIB and checklists for formatting text for visually impaired and dyslexic readers. The talks complemented this literature by demonstrating how some aspects of inclusive design, discussed in the literature, can be implemented in practice. Additionally, the talks demonstrate that designers need to consider the effectiveness of guidelines within specific contexts, needing to make informed decisions about when aspects of guidelines might hinder effective document use.

In the workshop, led by Rachel Warner, students evaluated a document in regards to inclusive design guidelines and checklists, producing recommendations for a document redesign. Students reported that they enjoyed this activity and the experience of putting theory into practice.

Outputs of the workshop demonstrated that students can grasp the application of basic inclusive design guidelines, such as type size, but need further support to critically evaluate when to apply guidelines and when to choose alternative design choices. An adaptation to the workshop would be to use the graduate talks to frame the workshop at the beginning of the session, rather than relying on students engaging with this content as GIS.

The Orbit 20 reader in use.

The Orbit 20 reader in use.