The ‘Discovering the Landscape’ series continues with a profile of Sylvia Crowe, ending with an overview of our Crowe collections. Written by Claire Wooldridge, Project Senior Library Assistant: Landscape Institute

The landscape architect has to understand what the people want and to understand what the wild life wants, as well as understanding the function of whatever it is you are undertaking. There is a great deal to think about…’

(Crowe quoted in Harvey, 1989, p. 51).

Dame Sylvia Crowe (1901–1997) was a landscape architect and writer. She was a significant figure in the promotion of landscape architecture in the UK and internationally, through her involvement with the Institute of Landscape Architects (now Landscape Institute) and the International Federation of Landscape Architects. Crowe was an active member of many prestigious organisations, such as being president of the Landscape Institute 1957-59 and of the International Federation of Landscape Architects in 1969. She was granted a CBE in 1967 and a DBE in 1973 (at which time the last landscape architect to receive such an honour had been Sir Joseph Paxton in 1851).

Crowe trained in horticulture at Swanley Horticultural College (1920–22), going on to complete an apprenticeship with Edward White at Milner, Son and White (1926-27). Crowe then worked as a garden designer for William Cutbush & Son’s nurseries (winning a gold medal at Chelsea in 1937) until the outbreak of World War Two. In 1945 Crowe established her own private practice as a landscape architect. Although they were not in partnership, Crowe was given a room in the offices of Brenda Colvin and in 1952 they moved together to 182 Gloucester Place where Crowe remained until 1982 with various staff assisting her over the years.

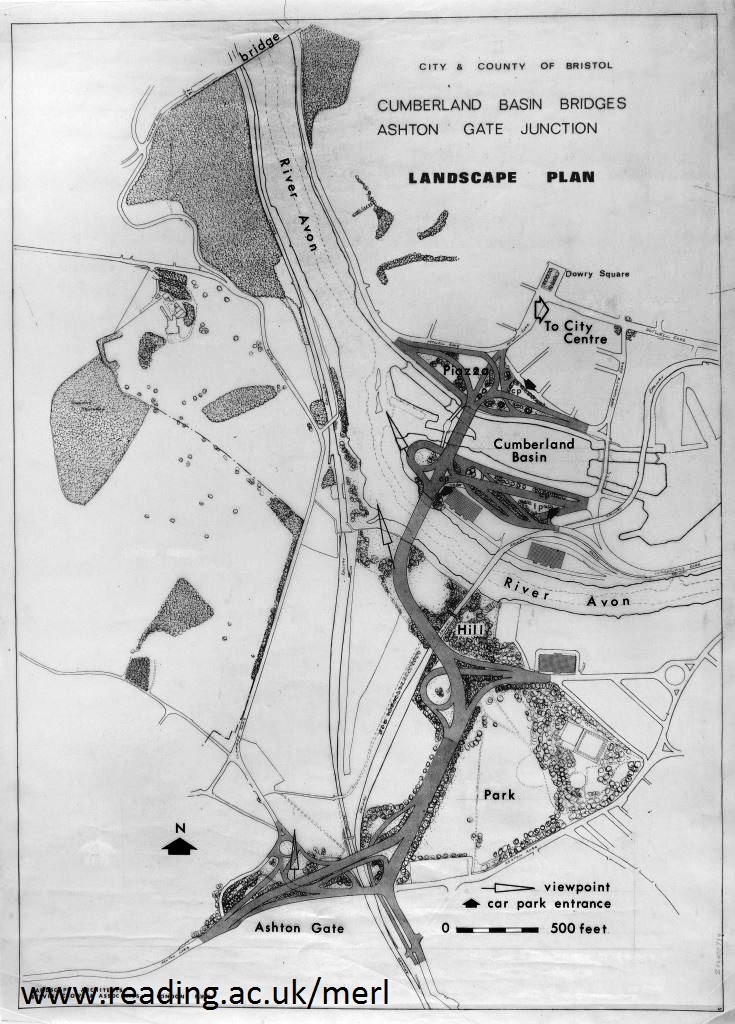

Crowe worked on a great range of diverse projects; from small gardens, to new towns, forestry initiatives and power stations. She authored many influential books confronting the challenges of new landscape issues and garden design, such as Landscape of Power and Tomorrow’s Landscape in the 1950s. Urban development Crowe worked on included Bristol in the 1960s. Crowe also designed the landscape around Wylfa power station, Anglesey and Trawsfynydd nuclear power station, Gwynedd, Wales (at the top of this post).

In 1964 Crowe became the first landscape consultant to the Forestry Commission, a role she worked in until 1976. During this period, Crowe revolutionised how the need for timber production can be balanced with retaining the beauty of the landscape, publishing Forestry in the Landscape in 1966. She commented: ‘I think that aesthetic and ecological principles are inseparable, certainly in afforestation’. (Harvey, 1987, p. 34).

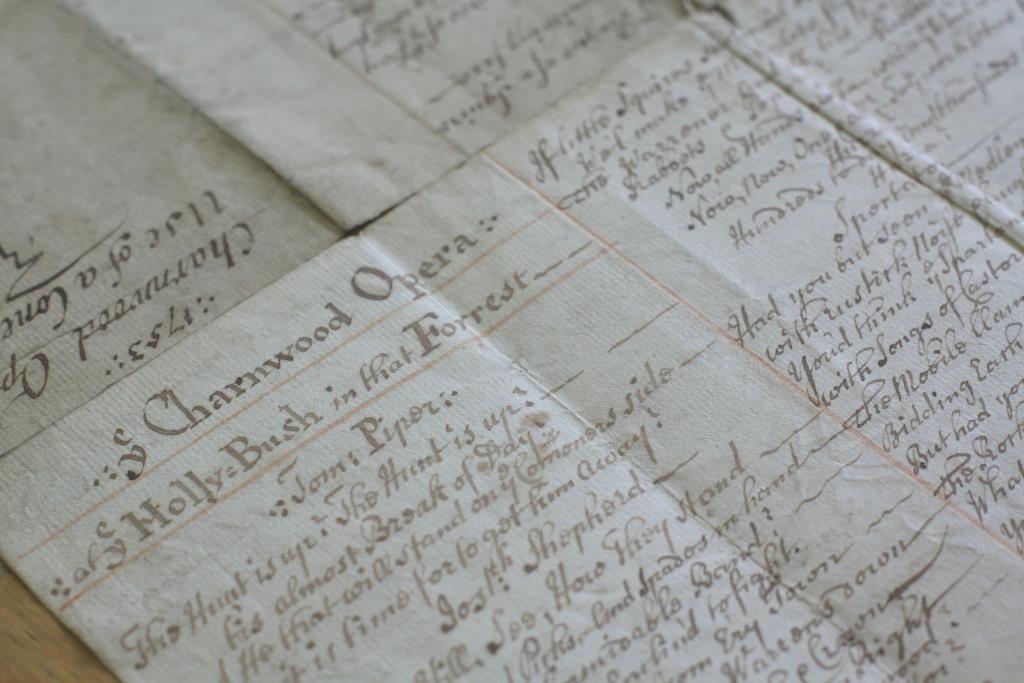

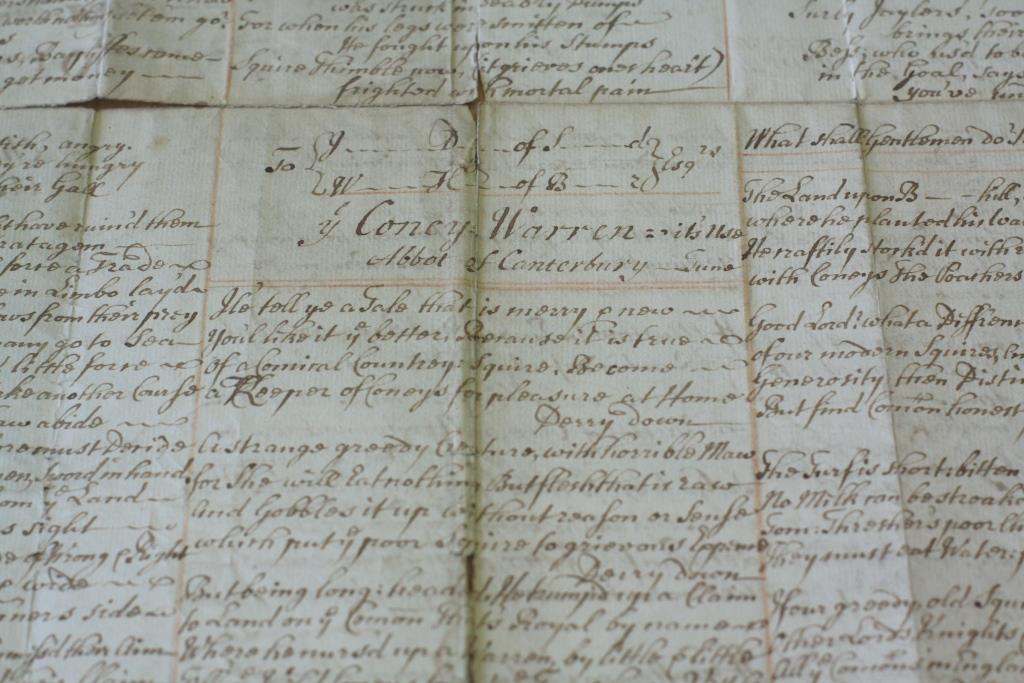

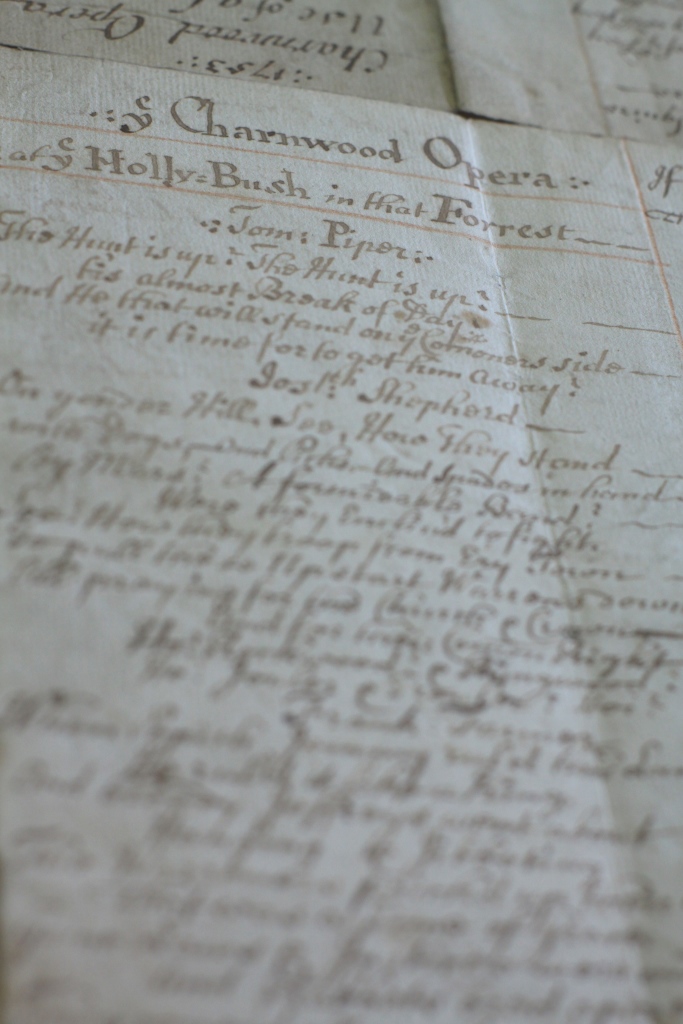

The Sylvia Crowe archive and library collection at Reading contains drawings by Crowe and some of her staff, photographs and negatives, and correspondence. The archive collection has been catalogued with the reference AR CRO and a handlist of the collection is available here.

Books from Crowe’s personal library have now been integrated into our MERL Library. We also have books written by Crowe that she gifted to other prominent landscape architects, such as the copy to the above of her Landscape of Roads (1960), with the inscription to the Jellicoe’s reading: ‘To Geoffrey & Susan, from Sylvia. A memorial to our battle of the roads?’.

As mentioned above, Crowe had many connections within the world of landscape architecture; for more information on our Sylvia Crowe, Milner White, Geoffrey Jellicoe, Susan Jellicoe or Brenda Colvin collections please

contact us at merl@reading.ac.uk.

For more information please see Hal Moggridge’s entry on Crowe in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Harvey, Reflections on Landscape (1987) or Collens & Powell, Sylvia Crowe (LDT monographs 2, 1999).