Written by Claire Wooldridge, Project Senior Library Assistant: Landscape Institute

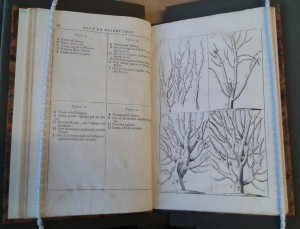

Title pages (from left to right, Instruction pour les jardins 1697, The complete gard’ner 1704, Il giardiniero francese, 1723)

This months ‘Discovering the Landscape’ looks at some interesting new additions to our MERL Library Reserve collection, drawing upon links between the Landscape Institute collections and our existing MERL and Special Collections.

We received several fascinating rare books from the library of the Landscape Institute. Here we look at two of these (La Quintinie, Instruction pour les jardins fruitiers et potagers, Paris : 1697 and (Dahuron, Il giardiniero Francese : ovvero, trattato del tagliare gl’alberi da frutto con la maniera di ben allevarli, Venice: 1723) alongside our existing Reserve copy of La Quintinie, The complete gard’ner : or, Directions for cultivating and right ordering of fruit-gardens, and kitchen gardens, London : 1704.

The three titles above are all translations of the same work, originally in the French (1697) by Jean de La Quintinie, 1626-1688. It is fascinating to hold the three copies of this text, to see how it was translated into Italian and French over the next two to three decades. This indicates the text must have been considered to be very important and useful, as the dissemination of the text in different European vernaculars in the early decades after its first publication reveals.

La Quintinie was the principal gardener of Louis XIV (1638-1715) of France and was responsible for the design of the Potager du Roi (the Kitchen Garden of the King) at the Palace of Versailles.

The work was first translated into English at the end of the seventeenth century, our copy was published in 1704. John Evelyn (1620-1706) the well-known English writer, diarist and gardener (e.g. Sylva, or a discourse on forest trees, 1664) produced the first English translation of Quintinie’s work. Evelyn was a prominent scholar of botany, gardening and natural history, meaning that his choice to translate Quintinie again highlights the significance of the work. He was assisted by George London and Henry Wise, who then went onto produce the condensed version published in 1704 we hold in our Reserve Collection.

René Dahuron (c. 1660-1730) translated La Quintinie’s work into Italian in 1723. Dahuron had worked under Quintinie’s instruction at Versailles.

All three editions of the work we hold contain intricate and delicate plates. Many of these are large fold out plates, several being of trees. Instruction pour les jardins fruitiers et potagers (1697) also includes a delicate fold out plate of a garden design (the top image, above). In addition there are lovely illustrations used for chapter headings, such as the two below, showing how the title is dedicated to the King.

For further information please contact us on merl@reading.ac.uk

References:

La Quintinie, Instruction pour les jardins fruitiers et potagers, Paris : 1697

(MERL LIBRARY RESERVE–4790-LAQ)

(MERL LIBRARY RESERVE FOLIO–4790-DAH)

(RESERVE –635-LAQ)