Professor of Social and Cultural History at Leeds Trinity University, Karen Sayer is our Gwyn E. Jones Fellow exploring rat control in British agriculture. She’s spent a lot of time looking for rats in our collections…

The MERL archive is full of interesting animal records; as you might expect, there are papers, pamphlets and books on livestock (cattle, sheep, pigs, goats and chickens), the animals used for draught power and advice literature and information about pests. The library alone provides an incredibly rich resource. But, there is also an incredible collection of photographs from the Farmer and Stockbreeder archive (among others), and a vast array of more than 800 film reels that range from the 1920s to 2005 across several collections, many with animal subjects. If we take The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) collection, there are 460 films from the period 1930-1989. These include American examples of information films like ‘Sanitation Techniques in Rat Control’ (US Army Communicable Disease Centre & US Public Health Service Federal Security Agency, 1950), on limiting rat numbers through the correct storage and collection of waste, and British examples such as ‘Feeding Habits of Rats’ (Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food Infestation Control Division, c.1950-1959), which records brown and black rats under observation.

Sometimes our research allows us to ‘join the dots’ and, having chased various rat tales around the archive last year, it seems very likely that ‘The Feeding Habits of Rats’ actually records the work of Dr S. K. Kon and Dr Kathleen Henry at National Institute for Research in Dairying. That Institute was reported on in 1938 by the Farmers’ Weekly and the two researchers are shown in a photograph for the article with the following caption: ‘Feeding experiments on some 400 rats. This is one of the interesting jobs carried out by Dr S. K. Kon, head of the Physiology and Biochemistry Department, here seen with Dr Kathleen Henry, the biochemist.’ The photograph here became part of a photo spread of 11 images describing the Institute’s departments and roles titled ‘Research and Advice’ (Farmers’ Weekly, 9 Dec 1938, pp. 30-31).

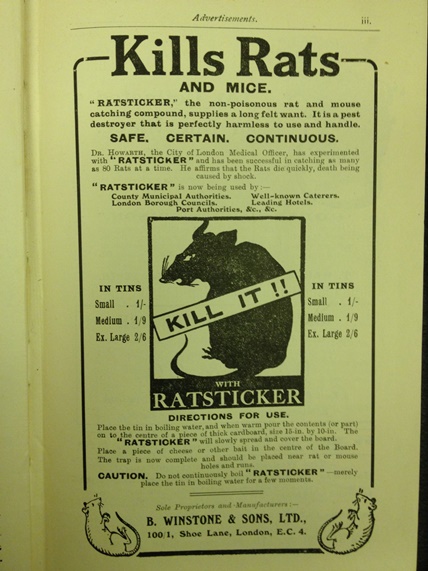

While I hunting for everything ratty, I came across what has become my favourite object: an extra-large tin of ‘Ratsticker’ “the Non-Poisonous Rat Catching Compound” manufactured by B. Winstone & Sons Ltd., 100/101 Shoe Lane, London, 1920. (Object No. 2008/64)

Ratsticker was a glue designed to trap rats and mice by sticking them in place, so that they died (it claims of the back of the tin) “quickly” their “death being caused by shock”. It came in small, medium and large tins for (1/-, 1/9, 2/6), and claimed to be “a great improvement on the custom of poisoning which takes four hours to kill.” A rather attractive tin, a little like that for Golden Syrup, illustrated in brown and gold, lettered with Art-Nouveau details and a serif font, it nonetheless has a gloriously gory image on the back of four dead vermin, stuck down next to a piece of bait. At no point does any rat control leaflet from the period suggest that glue be used, though there is an advert for Ratsticker in M. Hovell, Rats and How to Destroy Them (1924) a copy of whic I found in the MERL Library.

The Chemist and Druggist also carried adverts for it (Chemist and Druggist, 12th May 1923, and as David Drummond says in his wonderful British Mouse Traps and Their Makers, (2008) B. Winstone & Sons were not alone in making it in the 1920s suggesting a demand. Still, you’re left wondering: did it ever work? What actually happened?

Sticky traps for rats and mice are still in use. They do work, but they do not usually kill the animals by shock or anything else – they have to be killed by the operator, or they die of thirst or starvation, and sometimes gnaw their own limbs off in an effort to escape.