The Museum of English Rural Life has acquired 6 engravings for the collection, by print-maker Stanley Anderson RA (1884-1966). The acquisition was supported with the help of the Art Fund. We were the successful recipients of an Art Fund grant, enabling us to purchase the artworks at auction in December 2015.

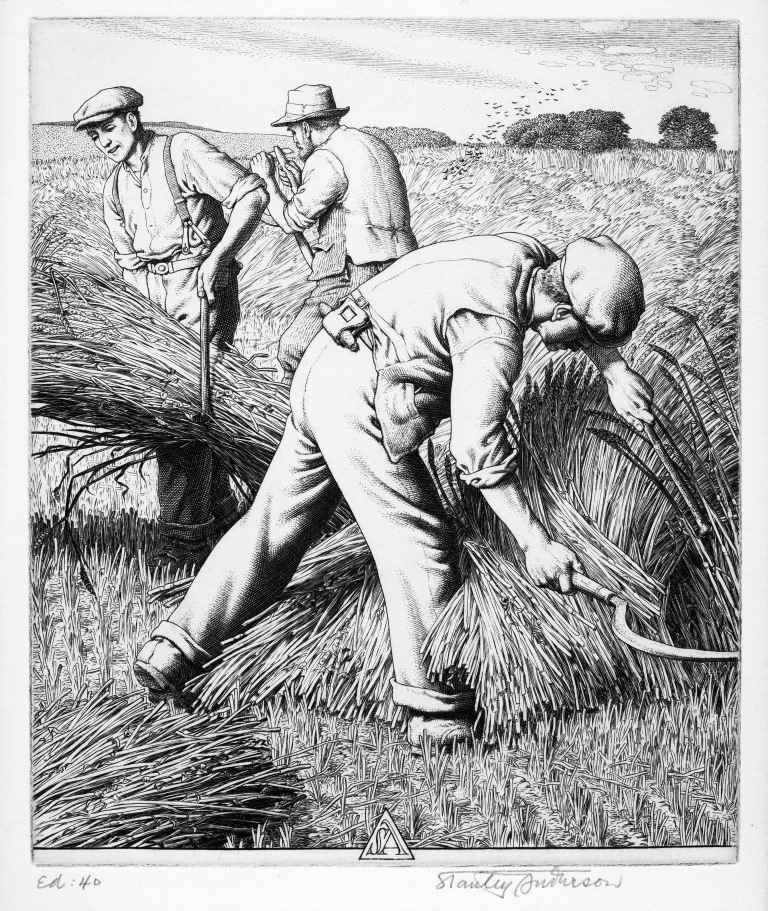

The Museum acquired a number of prints from Anderson’s ‘English Country Crafts’ series: The Thatcher 1944, The Rake Makers 1948, The Sadler 1946 and The Basket-Maker 1942. As well as two further prints: Eventide 1937 and Windswept Corn 1938. These new additions complement the existing holdings of Anderson’s work in the Museum collection (Making the Gate 1934, Three Good Friends 1950, Good Companions 1951 and Sheep Dipping 1934).

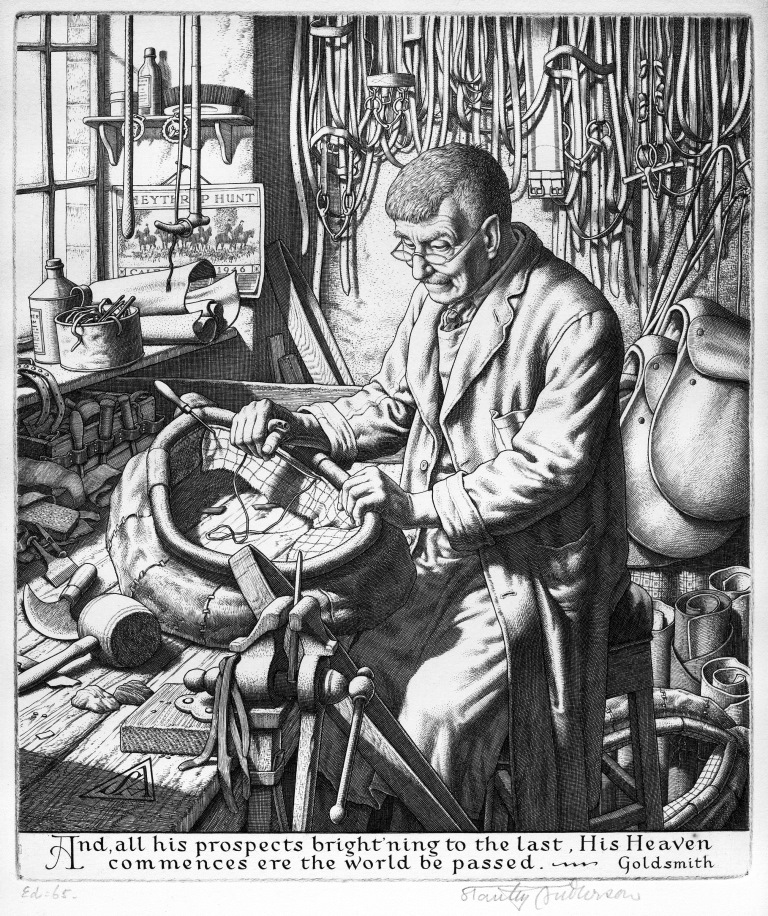

Stanley Anderson, The Sadler, 1934. © The Estate of Stanley Anderson. All rights reserved. DACS 2015

Anderson’s career

Royal Academician, Stanley Anderson, was an English painter and print-maker. He is best known for his prints featuring workers and craftspeople of traditional farming and handiwork practices, of which the English Country Crafts series (1933-1953) is most prominent. Arguably somewhat marginalised, Anderson’s printmaking career spanned nearly half a century and he is now attributed as being a key figure in the modern revival of line engraving.

Engraving involves the incision of a line (a design, lettering or image etc.) onto a hard, flat surface. This forms an intaglio printing plate. The printing plate is covered in ink; the incised lines hold the ink. Paper is placed over the plate and compressed by a heavy roller. The compression transfers the ink from the plate to the paper, producing a print. Multiple prints can be produced, making multiple editions.

Between 1909-1963 Anderson exhibited 183 works at the Royal Academy, he was the sole representative of British engraving and dry-point at the Venice Biennale in 1938, and was later awarded a CBE in 1951 in recognition of his contribution to the arts.

Anderson began his career in 1884 as an apprentice to his father who was a trade engraver in Bristol. Over the course of a seven-year apprenticeship he studied ornamental and armorial engraving, working on domestic wares. With a desire to move to London, Anderson won a scholarship for engraving from the British Institution. This funded his studies at the Royal Academy of Art where he studied under Sir Frank Short RA, an advocate of a Whistlerian tonal aesthetic. His early career was defined for the most part by cityscapes but, after the interruption of war, Anderson took a commission from a commercial printer to produce – in large editions – prints of landscapes, historic buildings and landmarks.

There is a growing appreciation of Anderson’s work. Last year, the Royal Academy produced an exhibition of his work ‘An Abiding Standard: the prints of Stanley Anderson RA’ and the associated publication of a comprehensive catalogue raisonné. A number of Anderson’s self-portraits can be seen in The National Portrait Gallery, together with an extensive collection of his work at the Ashmolean Museum.

Stanely Anderson, The Thatcher, 1944. © The Estate of Stanley Anderson. All rights reserved. DACS 2015

English Country Crafts

The English Country Crafts series may be seen to memorialise ways of English life – that were thought by many at that time – to be in danger of vanishing. Although his prints may convey a sense of nostalgia, we can say that Anderson was not yearning for the past. Instead, he was very much concerned with the present. His work represents a response to the myriad changes and mechanisations in society that he observed and so carefully documented. The English Country Crafts series, together with similar representations of farming, animal husbandry and traditional skills, depicted a range of subjects. His work demonstrates acute observations of an individual’s mannerisms, particularities and physical characteristics. Anderson captured many manual tasks that are now largely performed by machinery. He consciously recorded, and commented on, a disappearing and ageing workforce with striking detail.

Oxfordshire subjects

Later moving to a studio in Thame, Oxfordshire, Anderson knew and befriended many of the subjects featured in the English Country Crafts series. Anderson’s subjects lived and worked across Southern England, including Buckinghamshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Hampshire and Dorset. This local geographic connection gives the artworks great significance for the Museum, being based in neighbouring Berkshire. Visual representations of country life such as these have become a core part of what MERL seeks to collect.

Stanley Anderson, Making the Gate, 1934. Object number: 83/21. © The Estate of Stanley Anderson. All rights reserved. DACS 2015

Making the Gate depicts Thame-based farrier and blacksmith, Rupert Timms. On the back wall of his workshop, the designs for a gate can be seen pinned to the wall. Anderson himself designed this gate. This was in recognition of the diminishing demand for the blacksmith’s craft and in Anderson’s active promotion and diversification of alternative and sustainable blacksmithing skills. This print, as with others, is indicative of Anderson’s close affinities with, and appreciation of, manual workers and their craft.

Stanley Anderson, Windswept Corn, 1938. © The Estate of Stanley Anderson. All rights reserved. DACS 2015

Significance to the Museum

MERL’s interest in Anderson’s work is long standing. The Museum first exhibited Anderson’s work in 1958 in a temporary exhibition, ‘The Craftsmen and his Tools’. The Museum loaned 25 engravings directly from Anderson, which included 5 of the 6 engravings that we later successfully acquired through the support of the Art Fund. In the exhibition, these engravings were displayed alongside loaned craft tools from the R.A. Salaman Collection. The loan included objects such as a farriers’ tongs, a basket maker’s bodkins and a chair maker’s breast bib.

Anderson’s prints are robust in their reflection of the scope of traditional craft objects that we now hold in the Museum’s collection. They successfully illuminate and contextualise the objects and their use. The value of Anderson’s representations in facilitating our understanding of rural life and craft is described in the accompanying exhibiting guide. :

“The engraving [of The Cooper] provided an almost complete guide to the trade. If you look carefully you will find truss hoop, heading knife, jointer, cresset, adze, chiv, downright, stoup-plane, auger, rushes for caulking, dowelling brace, bick iron, hoop-driver, and heading-swift” (Salaman, 1958 p3).

Unique stories

We can identify and uniquely interpret the stories of the crafts people represented in Anderson’s work through our artefactual collections.

Stanley Anderson, The Basket Maker, 1942. © The Estate of Stanley Anderson. All rights reserved. DACS 2015.

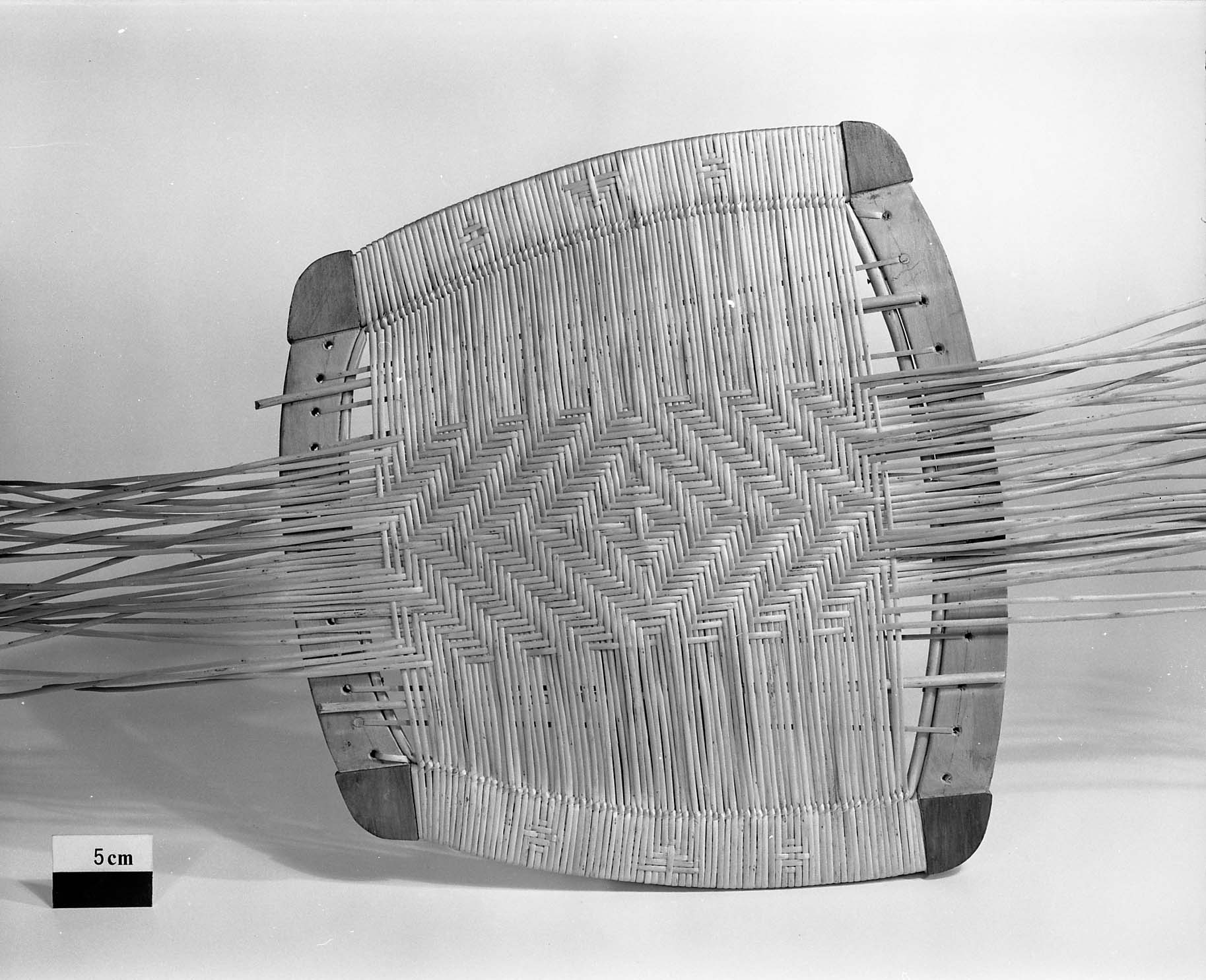

Thame-based basket maker William Youens Fleet is shown at his board making a half-bushel basket in The Basket-Maker, 1942. It is thought that Fleet was almost certainly related to the Maltby family who monopolised the chair seating industry in nearby High Wycombe, a centre of chair making. The Museum holds examples of Maltby-made seats and basketry.

This basketwork chair seat is an example of the craft of willow chair seating. It was made by Leslie Maltby, it is made of willow skein on an ash frame with an under weave of chair cane.

This basketwork willow bird cage was made by Leslie Maltby. It is round with a spire top and a door at the side, and would once have had a small platform outside the cage on which turf was placed to hold worms for food.

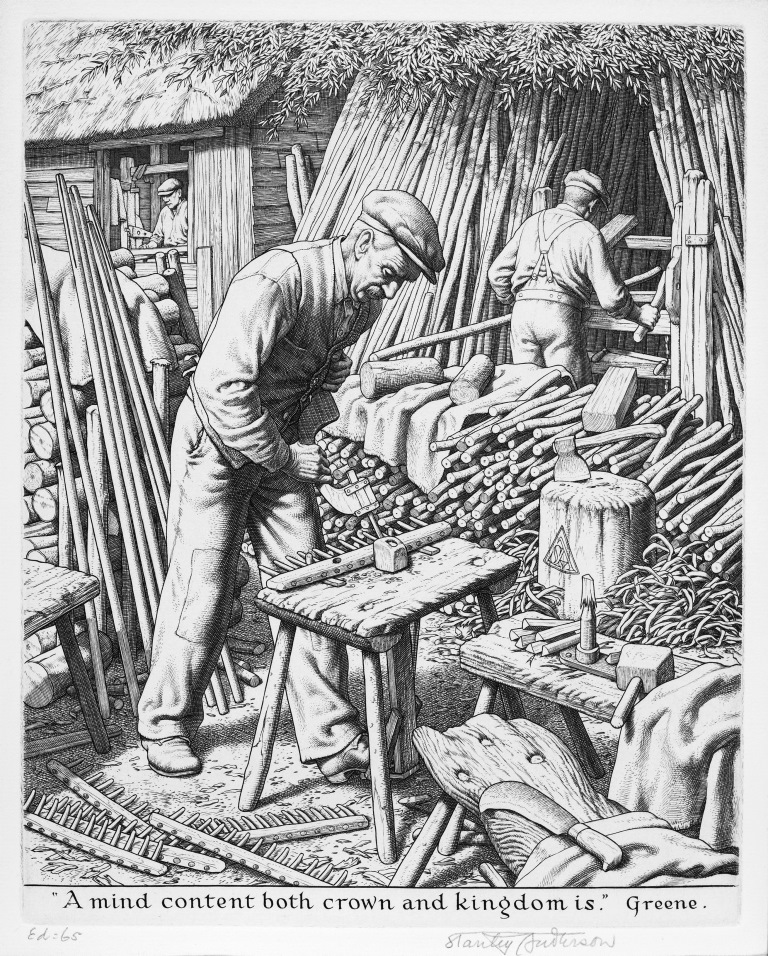

Stanley Anderson, The Rake Makers, 1948. © The Estate of Stanley Anderson. All rights reserved. DACS 2015

The rake makers firm depicted in The Rake Makers, 1948 is that of Ernest Sims of Pamber End, Hampshire. The Museum holds a number of rakes, rake parts, handles, and tools purchased from Sims.

This rake was made in the workshop at Pamber End on the 22nd April 1953; it is only half-made, so that the stages of manufacture are clearly seen. The rake is in two sections: the handle and the rake head.

Ten unfinished hay rake heads with holes drilled but no tines inserted. They are made of willow. They were purchased from Ernest Sims.

Access

We plan to display several of the newly acquired engravings in the Museum’s permanent galleries, due to open later in 2016 as part of the Our Country Lives redevelopment programme. However, the engravings can also be consulted by appointment. Please contact Art Collections Officer Jacqueline Winston-Silk for further details j.winston-silk@reading.ac.uk.

Art Fund

We would like to thank the Art Fund, the national fundraising charity for art, for their support in helping to purchase the artworks. This marks the first occasion on which the Museum has received an Art Fund grant. We would also like to acknowledge their support in enabling us to devise a bidding strategy that ensured our success at auction.