In this post Amber Roberts, recipient of MERL’s landscape academic engagement bursary talks about her work on our Michael Brown collection (Landscape Institute collections).

Michael Brown’s work is unfortunately little known to today’s landscape architects. Thanks to a generous research bursary from MERL I have been able to delve into his archive and begin to uncover Brown’s idiosyncratic approach, his lost landscapes and his lost research.

Brown (1923-1996) was an Edinburgh-born architect and landscape architect whose career had an international scope and strong links to key designers of the mid-twentieth century, such as Ian McHarg, Dan Kiley and Basil Spence. Brown’s projects covered all scales of landscape architecture and are of particular interest due to his commitment to integrating the theories and practices of landscape and architecture that resulted in a body of work that was both inventive and pragmatic. Brown stated:

The art and aesthetic delight of landscape must emerge out of solving down to earth problems elegantly and simply.

With this focus on the solution of ‘down to earth problems’, his work navigated the complex tensions of the profession that existed both then and now by advocating an objective, theoretical and interdisciplinary approach.

If spaces between buildings are to be used to their best advantage it is essential that methods of analysis and comparison be evolved which will enable the designer to analyse the functions and uses of external spaces very rigorously.

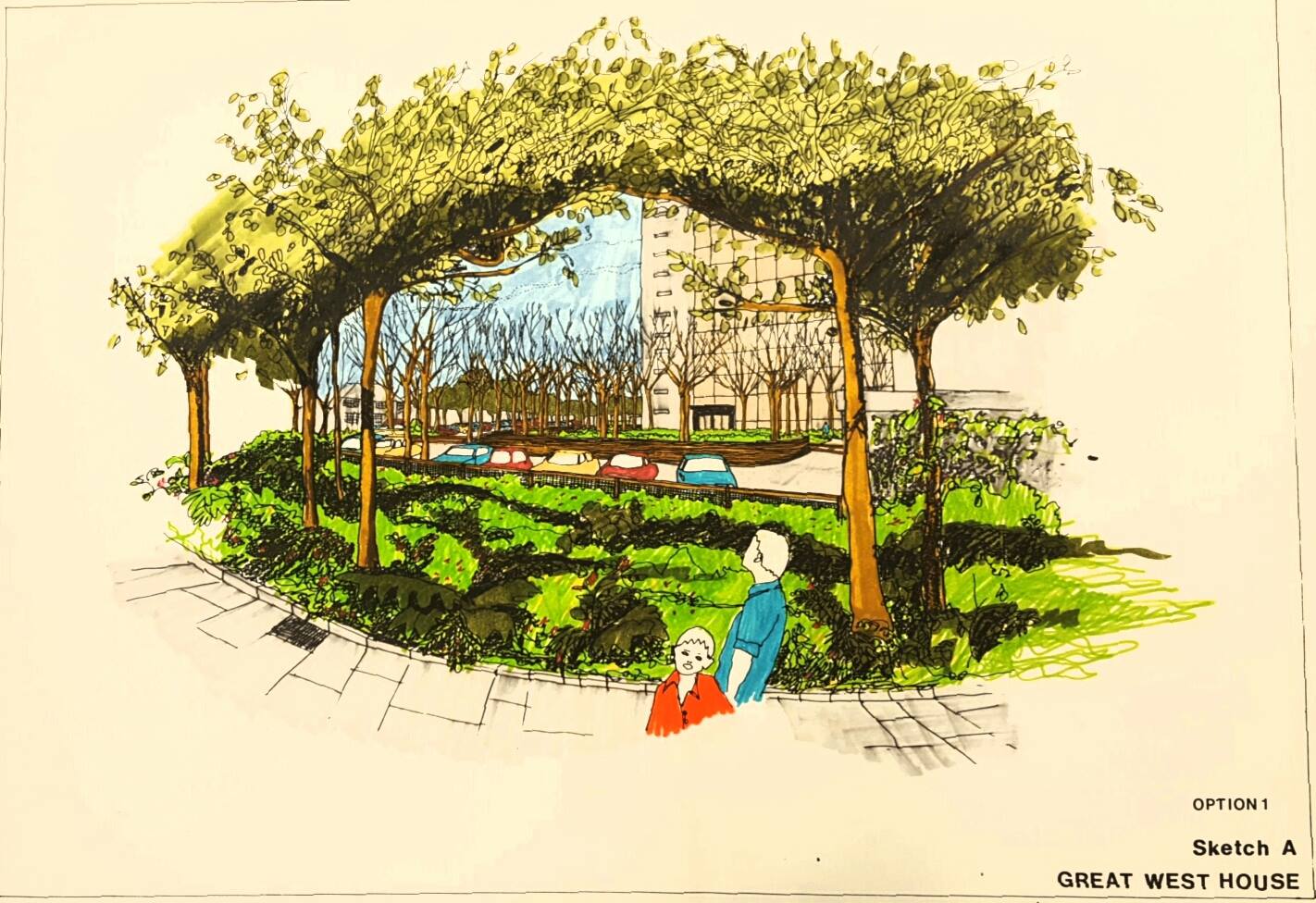

This approach is particularly evident in his work at Livingstone Road, London (1962 and later awarded a Civic Trust Award 1968) developed with the architects George, Drew and Dunn Partnership, a project that is due to be lost to a £300m regeneration project. By undertaking a disciplined survey and analysis of the site Brown identified key issues and opportunities that ranged from the particular microclimate of the site to cut and fill balance and pedestrian movement lines. Brown interwove this analysis with the ‘Court House Concept’ of his tutor McHarg to develop a series of spaces that were given careful detailing landform and levels to create a range of soft spaces.

Beyond the layout of the courtyard system of open space, Brown sought to foster a sense of ownership for the spaces among the new residents. This was a key approach of Brown’s that he had begun to develop during his early British work with SPAN Housing. Brown himself became a resident of Fieldend and member of the Resident’s Association for the upkeep of the landscape within the estate. The courtyards at Livingstone Road were each given a distinct character and function that was embellished with sculptures and wall panels and Brown actively promoted a resident’s association for the scheme.

Overall Brown had a deeply personal and idiosyncratic approach to landscape, his publications and designs offered exemplary solutions responding to complex issues from housing and motorway design to the design of public squares. Each of which combined his joint skills in architecture, urban design and landscape. Brown’s breadth of projects are testament to his rich and varied experience merging together disparate ideas and skills. This research on Brown will be presented with Lead Researcher Dr Luca Csepely-Knorr at the Society of Architectural Historians Conference in Glasgow next month.

Find out more about Amber’s work or our Landscape Institute.