Livestock portraiture depicting prize animals – cattle, oxen, pigs and sheep – began to appear in the mid-eighteenth century. We derive much historical value from these commissioned paintings through their collective recording of the process of English livestock improvement. It was a period in which livestock was being altered from medieval to modern purposes. In a time of rapid population increase, these adaptations were designed for one end: the production of meat to cater for the “the growing demands of the urban tables of Britain” (Trow-Smith, 1957).

We consumed not only the meat. New developments in the history of printmaking – such as mezzotints, aquatints and lithographs – emerged contemporaneously with the period of agricultural reform. A surge in the interest of scientific approaches to breeding, and the “mania for improvement” (Walton, 1984), meant enthused audiences readily consumed the reproductions as fashionable prints to be hung on walls.

Jacqueline our Art Collections Officer and Hillary our Post-Graduate Researcher working in the collection storeroom. Showing framed print 64/96, the ‘North Devon Ox’. Photo by Dr Martha Fleming, Collections Based Research Programme Director.

New ideas on the farm

Methods of livestock improvements included the shortening of the period between birth and maturity for meat-producing animals. Flesh was redistributed upon the most edible parts of the body, and the weight of the animal carcass was increased. Farmers developed a number of pioneering ways to achieve these adaptations. The in-breeding and line-breeding of cattle allowed the most desirable qualities to be selected, and fixed, by mating within a single breed. Out-crossing cattle allowed for new qualities to be sought across various breeds, and fixed in one new breed by mating. The latter could also include the import and use of animals from overseas on British stock.

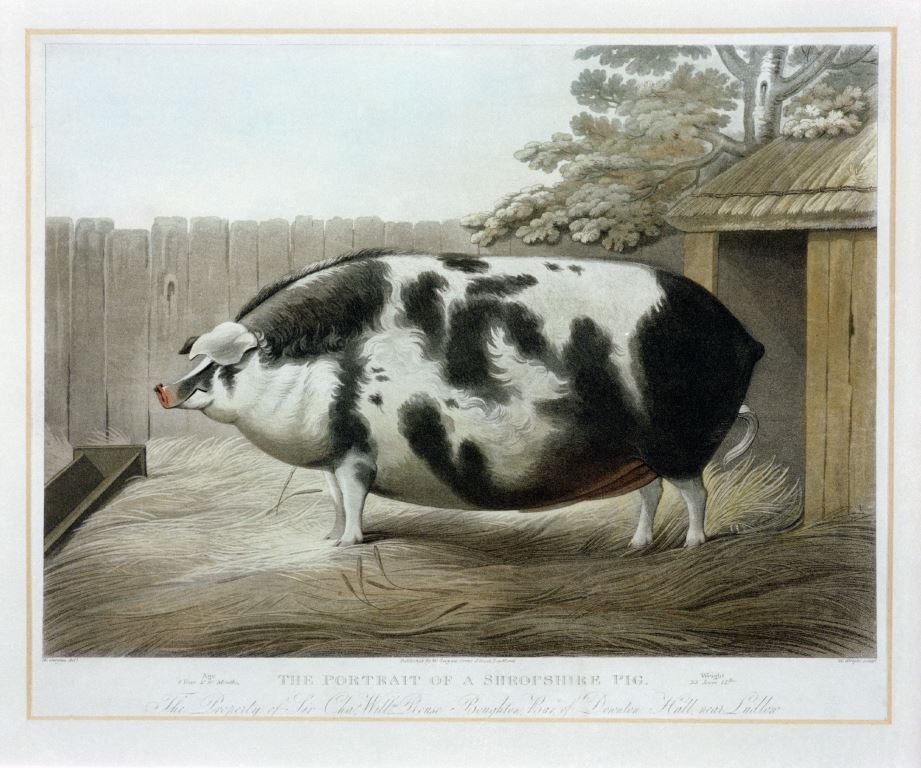

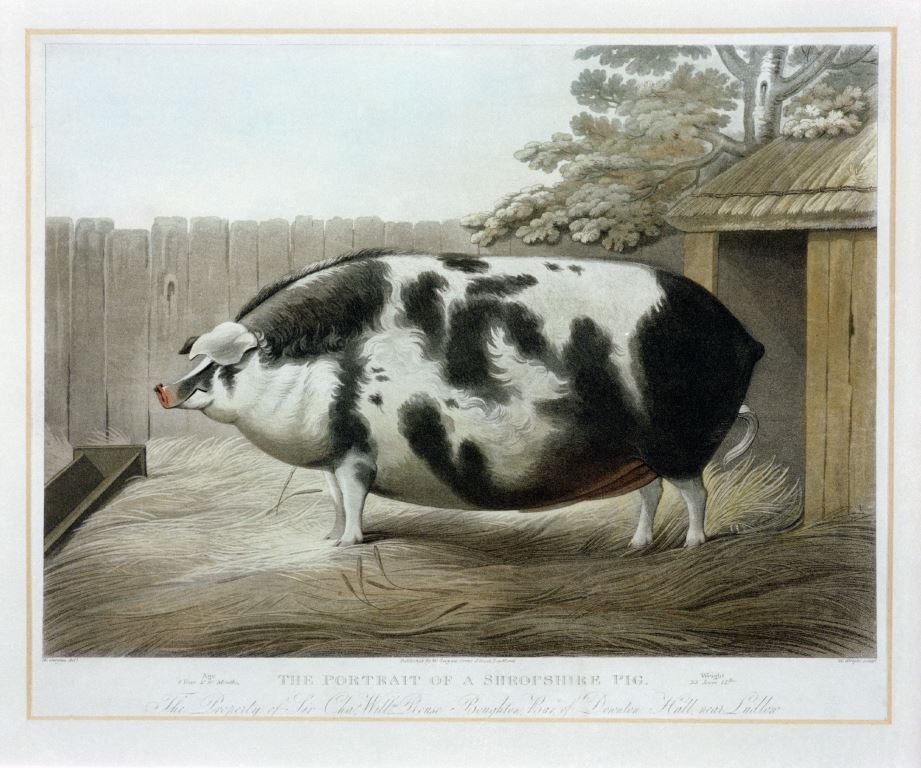

MERL accession number 64/100

This is a hand-coloured aquatint entitled ‘A Shropshire Pig’. It was designed by W. Gwynn, engraved by W. Wright, and published in 1795 by W. Gwynn of Ludlow, Shropshire. The pig depicted was owned by Sir Charles William Rouse Boughton of Downton Hall, near Ludlow.

Existing animals were diminutive when compared to the improved livestock bred after the mid-18th century. The growth was “rapid and wonderful, like their evolution into distinctive breeds” (Walker’s Monthly, 1936).

Livestock Portraiture

Livestock portraiture developed out of the tradition of sporting painting. Sporting pictures reflect a passion for field sports and country life. Under the patronage of gentleman, paintings depicted scenes of hunts and races, with portraits of greyhounds and horses. Examples of these prints and watercolours adorn the walls of a sitting room at Canterbury Quadrangle.

George Payne, Interior of a Sitting Room, Canterbury Quadrangle, Christchurch, Oxford. Mid-eighteenth century. Private Collection

MERL accession number 53/382

Agricultural enthusiasts followed suit and commissioned painters to record their favourite and prize winning animals. Paintings were prepared at the expense and upon the instruction of gentleman breeders for whom pedigree breeding was a fashionable hobby. The portraits, most often of a specific animal, were executed in side view and often included the individual animal’s name, pedigree and physical description. Over-fed animals were represented because of their high meat or milk yields. The animal’s physical appearance, corpulence and lineaments were captured by the painter.

Artists were often itinerant sign painters; a law passed in 1763 limited the number of shop-signs on London streets meaning craftsmen were looking for work. However, some painters were able to earn a handsome living from the patronage of their breeders.

Artists were often encouraged to over-emphasise the effects of improved breeding. In a 1964 catalogue of the livestock painting collection held at MERL, the author notes that the commissioner “paid for exactly what he held in his eye as the most desirable features … they were to be figured monstrously fat before the owners of them could be pleased” (Jewell, 1964).

MERL accession number 64/44.

This is a formal portrait, painted by Thomas Weaver of Shrewsbury in 1831. It is worth remembering that considerable licence was practiced – and expected – from the painter and engraver. Likewise, the preoccupation with fashionable breeds means the paintings are not always representative of the range of British cattle and sheep.

Painters

William Henry Davis is considered to be one of the most prolific artists. Already a reputable sporting painter, Davis responded to the demand for livestock portraiture by utilising lithography and publishing within his practice. Farmers’ Magazine, the agricultural journal, commissioned Davis to record winning animals at agricultural shows. This association lasted for almost 30 years and resulted in over 160 livestock paintings being reproduced in the publication.

MERL accession number 64/96

This is a print from a lithograph of a painting, entitled ‘Portrait of T. W. Coke and North Devon Ox’, c.1837. The ox was bred at Holkham in Norfolk and was considered to be the perfect specimen. Short-horn cattle feature most prominently in Davis’ work, but he also painted sheep and pigs. Davis’ prints declared he was ‘animal painter to Her Majesty’; however this was a self-styled title. This nomination was not uncommon and would be used by proxy if a painting had been purchased by a member of the Royal Family.

Consumption of images

With the establishment of agricultural societies, innovations in breeding received impetus by circulating new ideas in journals like Farmers’ Magazine. Publishing images of livestock portraiture in animal husbandry books was an ideal way of disseminating new practices to farmers, many of whom were illiterate. Early breeders were therefore not only “involved in improving their own livestock but conscious of the need to disseminate their ideas and advertise their practice” (Ayrton, 1982).

As agricultural societies spread and as methods of transport improved, animal shows were organised. This was an opportunity to bring together, in fierce competition, breeders and their stock. Prizes meant enhanced reputations. The subsequent demand for livestock portraiture to capture these decorated animals was high. The most remarkable beasts travelled as popular exhibitions and profitable wonders. Prints were sold as tickets or as souvenirs of the spectacle. The paintings and prints functioned both as advertisements for animals available to stud, but also to “reinforce their owner’s amour propre’” (Melly, 1982).

MERL accession number 64/40

This is a painting of ‘The Champion Shorthorn’, showing the shorthorn cow, a man and dog, with a landscape background. It was painted and signed by William Smith of Chichester in 1856. The Champion Shorthorn won 1st prize at the Chichester Cattle Show in 1856.

Portraits therefore up-held and reinforced the success of the improved breeds. “Breed was nothing more than an ingenious marketing and publicity mechanism. Certain identifiable physical characteristics were imprinted in animals of a particular strain, and prospective purchasers were then encouraged to associate those markers with some attribute or attributes of productivity… the success of a breed depended to some extent on the visual impact of the chosen marker or trade mark” (Walton, 1986).

Testament to their visual impact, the consumption of prints flourished. Producing prints to be hung on walls was an entirely new venture which emerged at the end of the eighteenth century.

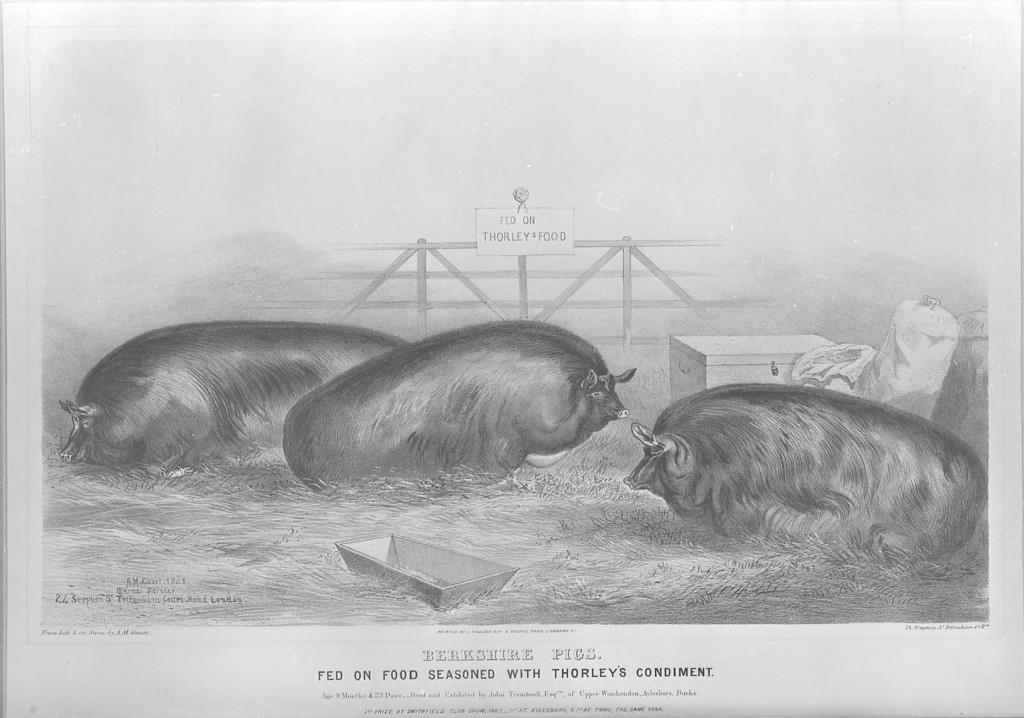

MERL accession number 64/82

This is a print from an engraving of an original painting, ‘The Durham Ox’, by J. Boultbee in 1802. It was engraved by J. Whessell of Oxford and was published by John Day in 1802. Over 2000 copies of this print were sold within the year.

Etchings, mezzotints, aquatints and lithographic prints are represented in the MERL collection. To satisfy commercial requirements, many prints are coloured by hand to replicate the original artworks.

MERL accession number 64/81

This is a coloured aquatint print of an original drawing by B. Taylor c.1819. The engraving was by Stadler. It is a formal animal portrait of a shorthorn bull, with a landscape in the background showing a bridge, Durham cathedral and woodland.

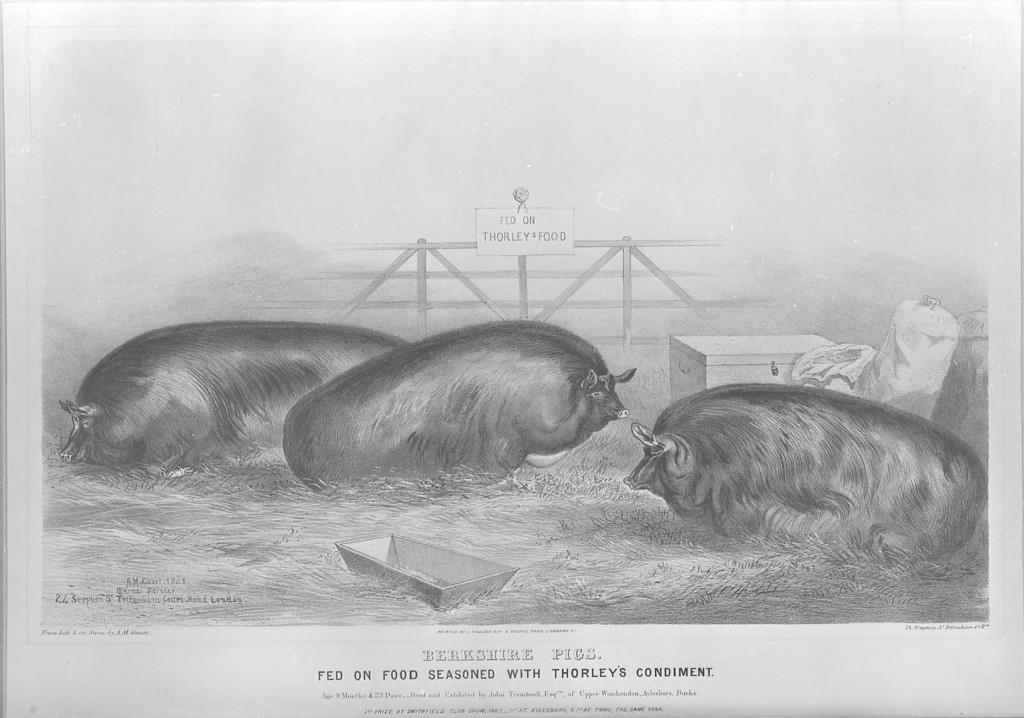

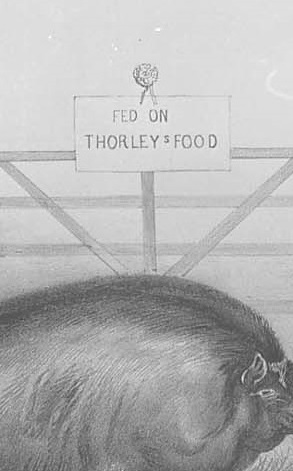

Operating in a time before photography, the artworks also became an important means of advertising. Manufacturers of animal food adopted the livestock portraiture aesthetic to foster early graphic sales promotions.

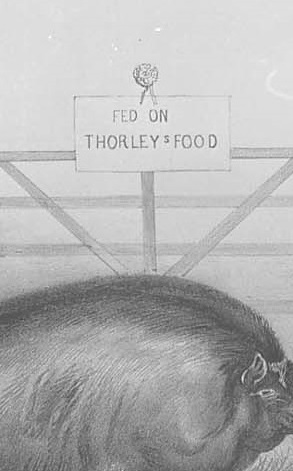

MERL accession number 64/72

Detail of 64/72

This is a tinted lithograph print from an original painting, ‘Berkshire Pigs’, by A. M. Gauci, of Tottenham Court Road, Camden, in 1868. The inscription on the print reads ‘Berkshire pigs fed on food seasoned with Thorley’s condiment’. The pigs won 1st prize at the Smithfield Club Show in 1867.

Collection and Research

The collection of livestock portraiture at MERL consists of both paintings and prints; it can be viewed by appointment. Queries relating to the collection can be forwarded to the Art Collections Officer Jacqueline Winston-Silk j.winston-silk@reading.ac.uk.

We are also pleased to welcome Hillary Matthews, a post graduate researcher, who has just begun working with the collection. Having previously studied agriculture, Hillary has just completed an MA in art history and intends to employ both of these disciplines within her PhD research, as she seeks to understand why many of these animals were represented in such an idealised way. Hillary will also look at their impact within their local rural communities as well as how they were received by the larger British public in general.

Hillary and Jacqueline consulted paintings in the collection storeroom after Hillary completed an intensive course in Collections Based Research last week, as part of her University of Reading doctoral studies. The work produced will further enrich our understanding of livestock portraiture in the MERL collection.

Jacqueline our Art Collections Officer and Hillary our post-graduate researcher working in the collection storeroom. Showing framed print 64/40, ‘The Champion Shorthorn’. Photo by Dr Martha Fleming, Collections Based Research Programme Director.