Written by Adam Koszary, Project Officer.

At the moment of writing, 198 lycra-clad men from across the world are cycling through the Cambridgeshire countryside. They’re riding the best bicycles in the world (with the best thighs in the world), aiming for a finish line at Buckingham Palace, the prize of a yellow jersey and a round of applause from the royal family.

It is of course le Tour de France, which held the Grand Départ in Yorkshire this past weekend. If you’ve managed to catch any of the action in between Wimbledon, the Grand Prix or the World Cup, you will also have seen the riders passing through some of the best scenery in England.

Leeds saw the Grand Départ on Saturday 5th July (Copyright Sky)

Cycling, to me, is the perfect way to see the countryside. It’s healthy, it’s fast and it doesn’t cost the environment. It’s also the perfect time to get cycling – alongside le Tour, we have the successes of Team GB in the Olympics, initiatives such as the new ReadyBikes in Reading (we have a station outside the Museum by the way), and growing government encouragement to thank for cycling’s current surge in popularity.

I didn’t have to look too far to find an important part of cycling history in MERL’s collection either. The ‘Boneshaker’ pictured below was one of the objects which caught my eye when I first visited the Museum, both because of its name and its strange appearance. It looks like an ancient prototype of the modern bicycle, something utterly unlike the sleek machines we have today. Instead of aluminium and carbon fibre, it is made of iron and wood; instead of disc brakes, it has a small wooden block operated by a string; and instead of gears and chains, it has its pedals attached directly to the axle of the front wheel. It doesn’t take much imagination to see how the bike got its nickname.

Yet despite the oddity of these features, it is the direct precursor of the modern bicycle – the essential parts are there after all, and all that is left is a process of refinement. This new type of bicycle began appearing around 1865, and it wasn’t until 1869 that bicycles with wire spokes began to be made. What had come before – more simple velocipedes and the hobby-horse – were inferior compared to it. However, it is worth mentioning that our Boneshaker was once mistaken for a hobby-horse, which has no pedals, before a Conservator added a pair to it in 1979.

In fact, the Boneshaker betrays all the fine craftsmanship of village carpenters, wheelwrights and blacksmiths. It seems a clumsy object only when compared with modern bicycles, whereas a closer look shows the elegant construction of the wheels, with the felloes (spokes) precisely arranged around a tiny hub usually 5 inches in diameter, as opposed to the much larger wagon hub.

The ironwork is also handmade by blacksmiths, and the fact that each of these bikes is bespoke makes you look again at the understated curve of the horizontal bar which allows a slight spring, and the almost ornamental braking system.

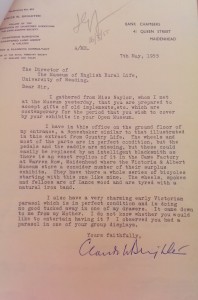

The Boneshaker is also an unfortunate nickname, which probably owes more to the state of the roads in the 1860s than the construction of the bicycle itself. This particular one was owned by Dame F.H.L. Clayton-East, who used to live in Hall Place in Hurley, now occupied by the Berkshire College of Agriculture. It was used to cycle around the grounds of the Hall, as it was illegal at the time to cycle on the roads (although you probably wouldn’t want to anyway). Before her death it was given by her to a Mr Claude Brighten, a chartered surveyor in Maidenhead. He was moved to donate the bicycle to MERL after reading an article in Country Life detailing the history of the Bone-Shaker, as well as visiting MERL, which at the time was a travelling open-air museum.

In conclusion, the beauty of the Boneshaker to me is as a piece of design. You can see in this bicycle of c.1865 the bare bones of the vehicle we have today, a design which has proven to be timeless.