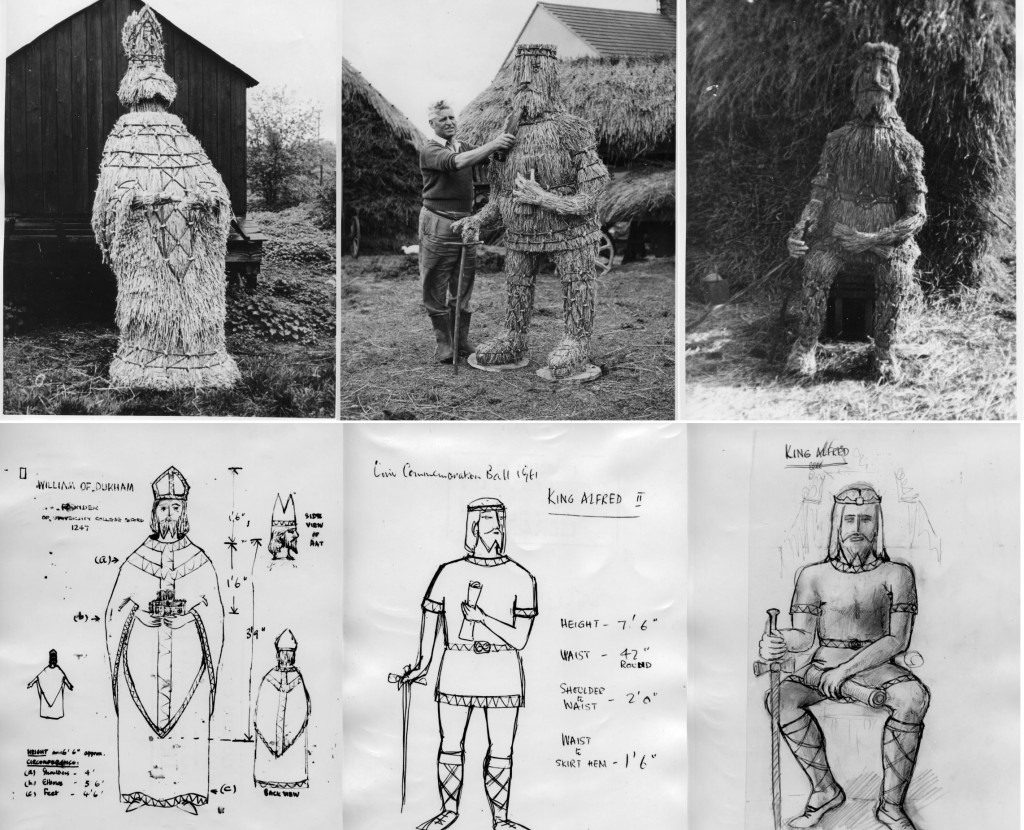

Pictured above are the original drawings and effigies made by Jesse Maycock in 1961. Our King Alfred, featured in the middle, has since lost his sword.

It was just before Christmas that marked King Alfred’s return to Reading, 1143 years after the siege and loss of the town to Ivar the Boneless in 871 CE and Alfred’s subsequent exile to a swamp (where he took up a bit of baking).

We’re not talking about the actual Alfred of course, the site of whose body remains shrouded in mystery, but our own thatched version pictured above in the middle. Our Alfred has not been in a swamp but for the past few months has been one of the star objects of Tate Britain’s British Folk Art exhibition, which has since traveled to the beautiful Compton Verney in Warwickshire. The aim of the exhibition was to address the neglect of folk art by the established art community, but also to ask why we shun it in favour of other art forms.

A very peculiar and individual object, our effigy was in fact one of three made by Master-Thatcher Jesse Maycock for University College Oxford in 1961 for their Commemoration Ball. Anyone involved in moving it can tell you that the effigy is solid, its rigidity achieved by a central pole and the working of the straw and osier peggings. Although similar in style to our straw-dollys it is made of ordinary rick straw and uses thatching techniques, rather than those used by straw-dolly makers. The other two effigies pictured above depict a seated King Alfred and William Archdeacon of Durham, respectively the mythical and actual founders of the College in 1247. The former is now at Stockwood Discovery Centre in Luton, while the latter sadly went up in flames.

For us, King Alfred has primarily been an example of a master craftsman’s work. He has, however, been very popular with families and captured the imaginations of our Toddler Time members, no doubt because our toddlers used to meet below his case, but also because he is simply more accessible as one of the few objects in our collection with a face! This relationship has continued as we redevelop, with our toddlers recently making their own stained-glass versions of Alfred for our shop window (shown above). As part of Our Country Lives, we hope to explore the more complicated associations and meanings behind our King Alfred, not least his legendary role in the making of both England and English identity. We have always known that he is well-made, sculpted out of straw and interesting to look at, but his canonization in the country’s foremost British art gallery means we cannot avoid treating him as both art and craft (although some would argue there is no distinction).

We would be very interested to hear what King Alfred means to you as well so please leave comments!