The second ‘favourite object’ has been chosen by Adam Koszary, Project Officer for Our Country Lives. Since starting on work at MERL, it seems he has developed a particular interest in ploughs. Read his personal reflections on the merits of the plough…

It is worth pointing out that before I started at the Museum of English Rural Life, I had only a vague idea of what constituted English rural history; in fact, it was the first time I had even heard the phrase ‘rural life’. I am also not alone. With increasing urbanisation (I myself am a product of the West Midland Conurbation) there have also been increasing worries that children are disconnected from the land – the most recently publicised poll revealed that a third of primary school children thought cheese came from plants and one in five thought fish fingers came from chicken. While statistics should be taken with a pinch of salt, there is certainly a disconnection between the world of the farm and the urban sprawl. For instance I had little knowledge of ploughs, which, when I talk about working at a museum of rural life, is the thing which immediately springs to people’s minds (often with a roll of the eyes).

However, the more I read about the plough the more I have learnt to appreciate it. Like the cow, it has been with us since pre-history, with rudimentary versions tilling the fields of the first domesticated crops in the Fertile Crescent, which in turn developed into the lighter, oxen-drawn ploughs by the Roman period. I recently finished Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel on my commute, a book where he attempts to explain why ‘western civilisation’ dominates the world. He forwards the compelling hypothesis that the success of western civilisation is due to accidents of geography and biology. In particular, the ancient domestication of crops and animals – with which the invention of technology such as the plough went hand-in-hand – is an essential pre-requisite of large-scale, complex societies. The plough may seem mundane to most but it is a practical, time-tested tool that has built the world as we know it. That the same tool has been with us for around seven thousand years is, I would say, on par with the timeless design of the wheel.

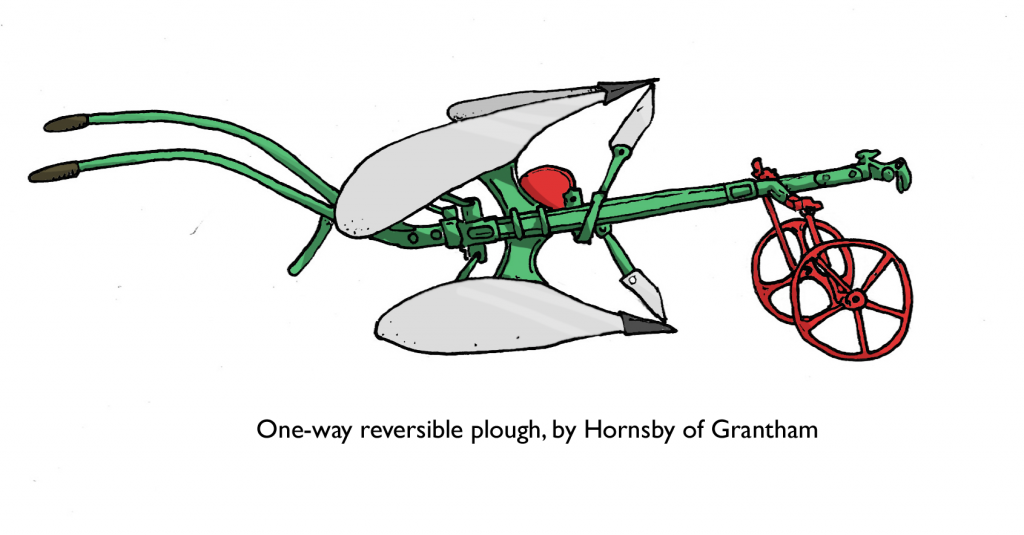

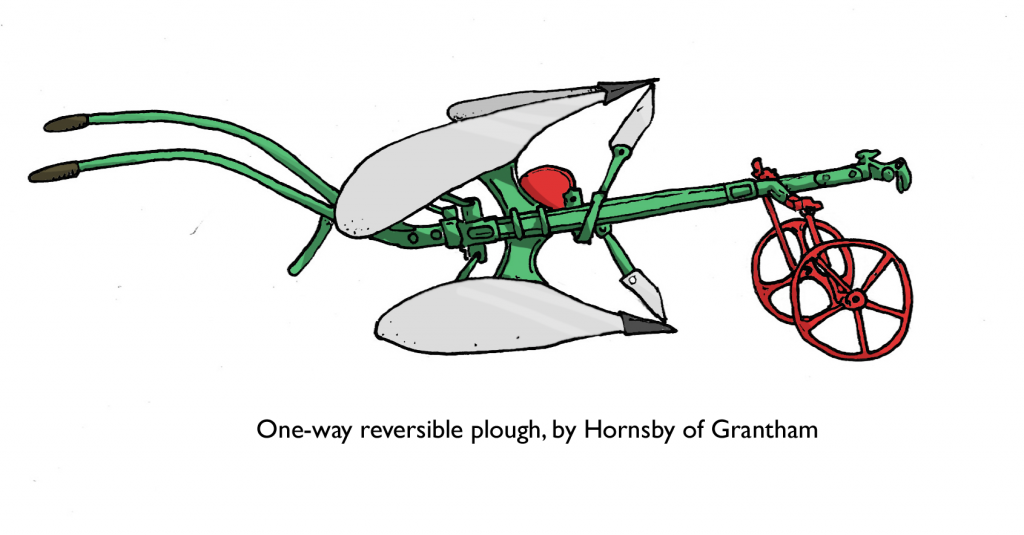

A Hornsby Reversible Plough (MERL/62/524)

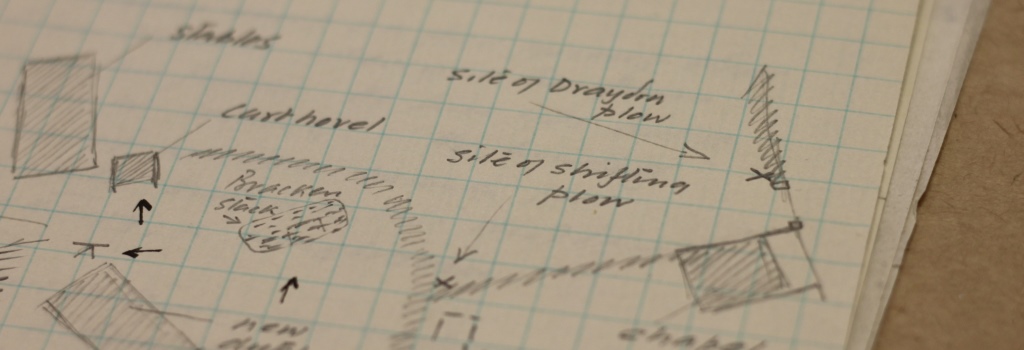

That is not to say that the plough has not gone through some variations, such as moldboards and cutting knives, but the essential purpose and design of the plough is relatively unchanged. I have been spending time drawing the ploughs on MERL’s walls on my lunch breaks, and my first victim was the One-way Reversible Plough, made by Hornsby of Grantham. Quite a rare example according to the 2011 Digging Deep plough survey (p.22), it is designed with two moldboards on the beam, so that when one is engaged on one side of the plough, the other is lifted into the air. It is also known as a ‘Butterfly Plough’ – a name which, to me, does not adequately reflect the number of sharp blades attached to the frame. In fact, my first sight of it put me in mind of B-movie slasher flicks, and I could easily imagine a Leatherface-type serial killer wielding the Hornsby plough, chasing a victim across the Yorkshire Moors.

However, I would have been better imagining it wielded by Margaret Thatcher, as Hornsby was an internationally important industrial manufacturer located in her hometown of Grantham, and credited with pioneering the track system for vehicles which would eventually be used on the first tanks in World War I. The company, bought out by Ruston in 1918, was eventually subsumed into English Electric in 1966, which in turn was bought by Siemens in 2003.

However, regardless of the fortunes of individual companies, the plough ploughs on, its fundamental design and purpose remaining the same despite technological advances. For Our Country Lives, it is my hope that the ploughs receive more attention in how they are displayed and interpreted, so that more people can better understand the significance of what they are looking at. MERL has an opportunity in Our Country Lives to fight the kind of ignorance cited at the start of this post, and it can often be as easy as finding new ways to interpret hackneyed objects such as tractors and ploughs in a manner which makes people look at them differently.